In Tanya's Words...

I am compelled by embodiment. “I wonder broadly about how we have continued to insist on our Indigeneity (Alutiiq-ness or Sugpiaq-ness in my case) even in the face of dominant structures and systems that have actively dismantled our languages, minds, and relationships to ourselves” (Tanya Lukin Linklater, Slow Scrape, Ed. Michael Nardone, The Centre for Expanded Poetics and Anteism, Montréal, 91). The ongoing disruption of our homes, homelands, and our Indigenous structures has been been met with our insistence. This insistence is present in Indigenous communities across Turtle Island (North America). I gesture towards that ongoing work in different ways: by reckoning with histories in the present moment and honouring Indigenous art and dance histories.

My artistic practice gestures towards the political, cultural, social life of our peoples in Indigenous communities across Turtle Island. It is not the thing itself, meaning that my artistic work does not do the cultural, political, or social work of our peoples. It cannot stand in for grassroots political organizing, families learning their Alutiiq, Cree, Anishnaabe languages, or intergenerational teachings of old style jingle dance, for example. However, it is my intention that my work does something in the world.

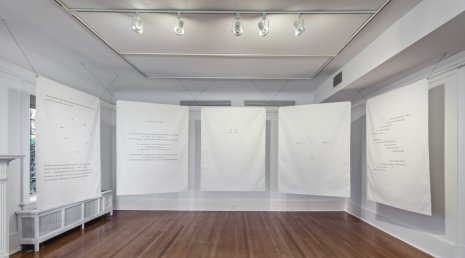

My practice evokes a kind of liveness, previously in open rehearsals with dancers and composers in the museum, in performance and works for camera, in considering the bodies of sculptures and cultural belongings; in an approach that centers conversation, visiting and listening. I consider Indigenous cultural production a way to potentially strengthen ourselves.

As I have said elsewhere, “History sets the current conditions under which we live. This is particularly evident for Indigenous peoples contending with difficult histories and conditions within settler colonial states on Turtle Island…I am weary of reducing [or containing] Indigenous ideas as we contend with this reductiveness, [containment and erasure] daily.” (Catherine Wood and Tamsin Hong, Our Bodies, Our Archives: BMW Tate Live Exhibition, online, Tate Modern, London, England)

“I have spent much of my lifetime learning within Indigenous spaces; whether that’s on the land and water with my father in my Alutiiq homelands in [the Kodiak Island archipelago of southwestern] Alaska, or with … Anishnaabe and Cree peoples in the Rocky Mountains … in Alberta, or Ontario. Many of these Indigenous networks have been invisible except to the communities and peoples who have been active participants. These spaces have been formative for my thinking. I apply what I have come to know to my practice in ways that might not be visible.” (Catherine Wood and Tamsin Hong, Our Bodies, Our Archives: BMW Tate Live Exhibition, online, Tate Modern, London, England)

In Alaska Native dances and in powwow we dance alongside one another. The viewer is also active within these contexts. There is an energy moving between the dancers, the sound moving amongst us, including those who have gathered.

That’s how I imagine the organizing force of felt structures. Felt structures might be described as the space between us. I also come to think of felt structures as atmospheric, ever-changing, on the move, mostly invisible like our shared breath, of the body and surrounding us simultaneously. They might be the charge that exists between us that is intangible yet impacts our minds, our ways of seeing, of sensing.

While the felt structures that I evoke in my practice are connected to the specificity of my lived experience as an Alutiiq or Sugpiaq person and citation of Indigenous dance, I feel that these are urgent considerations of our time. The way we feel one another, the land, water, and other non-human persons — for our collective survival and wellbeing we must reach towards other ways of being in relation.

I have had a distinct relationship to the museum for much of my life visiting the Alutiiq Museum and completing an internship there as a youth. I have read accounts of our relatives traveling to museums across the world to visit Alutiiq cultural and material belongings and their felt responses to these visits. The Alutiiq Museum opened in the mid-1990s after Alutiiq peoples in the village of Larsen Bay repatriated ancestral remains from the Smithsonian. Other Alutiiq folks testified during Congressional hearings for the passage of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. Collectively we dealt with the aftermath of the Exxon Valdez oil spill that impacted the lands, waters and animals of Kodiak Island, Alaska (and other communities in Alaska also grappled with this).

Our peoples are working to put the pieces of ourselves back together again after waves of colonialisms (Candice Hopkins) that have displaced and dispossessed our understanding of ourselves.

In 2021 I am writing alongside projects I’ve produced in the last couple of years. It feels as though we are collectively in a moment where time has slowed. I imagine that my work will continue to circulate as Indigenous ideas in writing, in museums, and elsewhere but changed by this time in unanticipated ways.

The Herb Alpert Award in the Arts affords me the possibility of time and the quiet of focusing on my practice. A group of Indigenous architects in 2018 asked how I might envision a space for Indigenous performance. Poet, Layli Long Soldier, and curator, Candice Hopkins, have both reminded me in recent years that the land is the place we return to and has the potential to be/is outside of domination. I am concerned with continuing to imagine practices of liberation.