Chapter One

Christian Scott aTunde Adjuah and Steve Coleman relished the opportunity to have an extended conversation – the first ever - and decided they could communicate best by telephone rather than emails. While they well knew each other’s music, had played at the same festivals - Christian said he’s seen “Mr. Coleman” play at many times - they hadn’t ever played together. Christian first started listening to Steve Coleman’s music when he was 13 years old and speaks of him as a ‘teacher’ for whom he has “reverence for his contribution, voice, output and clear impact on [my] generation!” [Steve Coleman is the recipient of the 2000 Herb Alpert Award]

– Irene Borger, editor and director, Herb Alpert Award in the Arts

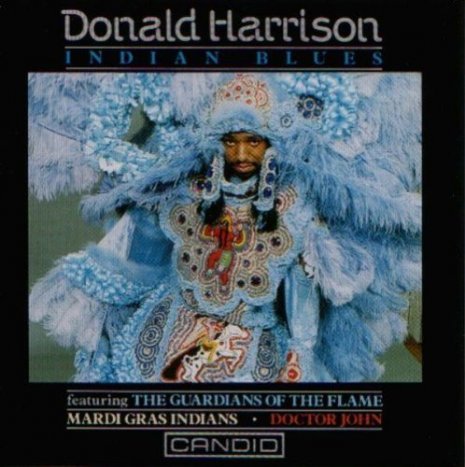

I think that comes directly from my family. My grandfather Big Chief Donald Harrison Sr. was the only man to be Chieftain of four different tribes of the Afro New Orleanian masking/unmasking culture of Louisiana regionally know as Black Indians or Mardi Gras Indians. The latter, for the record, is a term I abhor, as it is a reduction and gives the impression that a 300-year-old American culture and expressions of culture are nothing other than carnival revelry, when, in fact, Blacks were not allowed to take part in the Mardi Gras of New Orleans for many years. Liberated African and First Nation Tribes of the region did intermarry, live, work and fight for survival together. The cultural space I was born into is, however, a West African style Chiefdom that exists within the Greater New Orleans area with multiple histories and thread lines that start as early as the 1720s with the arrival of West Africans to the region. As it exists now, it is a living culture of pride and resistance that has developed many iterations in the past few centuries. Part of the tradition honors the Native Americans whom often gave sanctuary to self-liberated African survivors of the Middle Passage and their descendants who escaped enslavement in colonial and antebellum Louisiana. From the Reconstruction Era through the time of The Black Codes, in New Orleans, the classification of Natives and Blacks was the same, Negro. There was no differentiation in censusing or in the law for a time. This also did a great deal in terms of strengthening the bond between these groups. The masking/unmasking element of the culture that exists on Carnival day/Mardi Gras day or St. Joseph's Night, is done to celebrate the Chief and pay homage to ancestors. On carnival day you'll see the tribal banners meet each other throughout the Black neighborhoods and in the processionals held in spaces like Hunter's Field and Shakespeare Park. Each tribe has a different way of celebrating their ancestors' Chieftain and Chieftess.

There are a few ways one becomes a Chief. First, bloodline. Donald Harrison Jr. to whom you are referring is the eldest son of Donald Harrison Sr. As his son, he can either start his own banner or take over one of his fathers. You can also become Chief by being picked by a Chief stepping down and giving you the gang or by those who mask for a particular banner (note: the ranking members of the tribe). This determination is based on your deeds, integrity, personally and most importantly for what you can do to build and protect the community. Traditionally, appraisal for this role begins in early childhood. The modern iterations of these banners were erected to protect the black and native peoples of New Orleans from oppression, assimilation, and cultural annihilation after emancipation in the 1860s. Some have centuries-old histories of engaging. Wars in the region dating back to the arrival of the French through the time of the Spanish and eventually Americans, these people have fought to protect one another. Prowess and skill as a warrior, a beadsworker, orator, or the ability to lead the second line can all be called upon to nominate a new chieftain. Donald Jr. has been Chief for almost two decades. I was coronated as chief in 2017.

Appraisal for that role can start very early. My mother is the Chief’s youngest daughter so my participation begins around the time of my 5th birthday. So, that’s 32 years of complete commitment to the aforementioned cultural tenets and ways of living that lead to me repatriating one of my grandfather's banners, ‘The Brave." You’ll find these banners don’t use their actual names in New Orleans. They all use pseudonyms instead of the actual core tribal designation. One would never say I’m Fon, Ga, Igbo, Bambara, Wolof, Songhai, Atakapa or Chitimacha, they would say they’re Creole Wild West or 9th Ward Hunters. The culture is incredibly secretive in that it is built to preserve aspects of the American story vastly different from the traditional narratives of George Washington crossing the Delaware. The people have had to fight for the right to be who they are and were since the 1700s so forgive some of my vagueness.

They would have no reason to speak on it, as far as I know, their interaction with it would not exist without their respective relationships with Donald, Jr. There are many different Black cultural expressions and lineages in New Orleans. Some guys come out of brass band traditions, others the church. Some cats learn in school, this is our family’s particular way. When I was a boy I used to sit and listen to men like Danny Barker or Doc Cheatham and eventually I started to play music, they were in my neighborhood, literal Legends, Gods of the beginnings of this music right there walking around. So, all of our entry points are a mixed bag. We know this culture is at the root of some of the music and is who we are so, when we’re asked, we try to tell the story from our entry point. My granddad had one of the largest collections of Jazz recordings in New Orleans -- over seven thousand records. Most were gifted to the New Orleans Center for the Creative Arts upon his passing. His wife, my grandmother, was a composer and clarinetist, my mother and all of her siblings played; she was a double reedist, a bassoonist. In other words, you can pitch a rock and hit an amazing trumpeter in New Orleans. The sound is everywhere and the entry points to music vast.

Most people think second lines are a type of parade. They aren’t. Traditionally the second line is a component of many New Orleanian processionals. The second line actually refers to the second wave of parishioners that take part in the processional. So if you have a Jazz funeral for example, you would move the body from the church or whatever the house of worship, to the person's final resting place. From the house of worship to the gravesite people close to the recently departed would represent the First line of parishioners. During that time dirges and somber music are being played but once you deliver the recently departed, the tone shifts to celebrating that person’s life. The change in tone signals the rest of the community who may not have any relationship to the funeral to come out and celebrate this person’s life. That second wave of people are what we refer to as the second line. They're different traditions.

Right, the first line of parishioners is the family and the people mourning. The second line of parishioners is the people that are not related to that, that are still offering support and love and positive energy in that moment.

No, not the same neighborhood, definitely not from the Black tribes. I'm from the Upper 9th Ward. I know Mr. Marsalis as my predecessor's teacher at NOCCA (i.e., New Orleans Center for Creative Arts) in the 1970s. We didn't really have a relationship. I used to love playing Swinging at the Haven though! What a tune. People like Clyde Kerr Jr. (trumpet) Kid Jordan (tenor sax), Alvin Batiste (clarinet) Jonathan Bloom (drums) Kent Jordan (flute) Germane Bazzle (vocals); these are the people that would walk around the neighborhood and ask you have you brushed your hair and if you know who Clifford Brown was. As far as I know the only musicians that come directly out of the tribes are Donald and I, Idris Muhammed (drums) who masked with little Donald, his great-nephew Weedie Bramiah (percussionist) who is in my banner, Joe Dyson the drummer and the some of the Neville Brothers. Donald Jr. is the first to bring the sound back into Jazz with a record called Indian Blues. I think it was released in 1991.

I can't say yes or no. From what I know, in New Orleans, that was a territorial thing.

So if there was a hunter really firing the horn up for his neighborhood, they were gonna anoint him. The bands in New Orleans have battled from the very start. Sidney Bechet talks about that in Treat it Gentle, his autobiography, Chiltons' Wizard of Jazz talks about that also. Something happened that kind of blew my mind recently in Chicago that's related. There was a little boy at a concert we played at the Harris Theater who came up to me mid-concert, 1,500 seat capacity room, and walks right to the stage. The heart on this cat, man I'm tellin you! Told me he needed a trumpet and didn’t have the means. This little guy's spirit was so strong man, I asked him if he’d promise to practice and he said yes. I couldn’t find him after the set so I asked the staff at the theater to try and track him down and they did. The next time I came to Chicago I brought a brand new Bach TR-700 for him. Upon giving it to him the crowd started to scream “Lord Jermal Lord Jermal!” Now, he hadn't played a note but that connection was there. These things don't just fade away.

I wasn't around at that moment but I was raised under the New Orleanian masters that are the children and grandchildren of some of these figures. Can’t say how they got the monikers but I would gamble they stuck because they were the Real McCoy.