Chapter Two

That’s never seemed like a remarkable concept to me. Then again, I’m an Asian guy from Indiana, and so I was brought up romanticizing a particular brand of Midwestern humility. The dignity of just putting your head down and doing your work, and if you want something done then the most honorable thing is to hunker down and do it yourself.

Maybe it does help with rejection too. Of course there's a lot of rejection in this line of work, and this might sound... I don't know, disingenuous or delusional, but I honestly don't worry about rejection that much anymore. It doesn't have the same sting it used to. Maybe this is about getting older, but I think it's more about being in a place where I'm way more into the journey than the product.

This is where my job at The Lark has been useful, in fact. Because it's a process-based organization, where every level of the mission is about creating space away from thinking about commercial pressures, critics, ticket sales, and that kind of thing, to put writers in a position to hopefully do their most raw and vulnerable, adventurous and untested work. It places the value of what we do on how useful it is, rather than how "good" it is from the various arbitrary indicators of what success is in our field. We get to define success based on how it feeds into what we do next, and next, and next. It's not about putting on a show, it's about building on your entire artistic journey.

I was working on a show many many years ago, I won't say which one, but it wasn't going well. We were nearing the end of previews, and I was at The Lark, feeling very anxious and distraught. My boss, John Eisner, said “hey how's it going,” and I said, "Not good, John!” and he said, "Well, it's all process." I got very frustrated and said, "No, John, it's not process anymore, there are paying audiences coming, critics on their way, expensive sets and costumes, and all these fine people who memorized all these terrible lines I wrote and none of it works," and he said in an infuriatingly calm way, "Well, unless it's the last thing you ever do, it's still process."

That comment didn't help me at all at the time, but I've thought about it a lot since, and I think I've internalized the idea for real at this point in my life. I can do something that doesn't work, and feel okay about it. Because if I'm not trying things that might not work, then what the hell am I doing? So I always come back to process, and zooming out long-range helps with navigating the short-term rejections and missteps.

Okay, I see where you're going with this. Because yeah, even though I say nobody owes me anything, I suppose I do kinda feel that I owe something to others. Throughout my life I've taken on a fair amount of responsibility, and I've worked really hard in what you might call advocacy and support positions, in service to other writers. From my work with Second Generation back in the day, producing works by lots of other playwrights, co-directing the Ma-Yi Writers' Lab, serving on the Dramatists Guild Council, and, of course, The Lark and those sorts of things. But to be honest, that kind of work is basically selfish. It's part of what supports me.

Because here's the thing: in this industry, it's very easy for freelance playwrights to get into a big emotional trap. It's set up this way. We're set up to hustle to get our work out there, to get it produced, to build relationships with producers, directors, literary agents, in service of building a sustainable career. And that can feel very lonely and isolating. To be in a position where your plays, and your plays alone, are how you express yourself in the world.

I'm very lucky to be in a position where I can see how my work exists in an ecology. In my job at The Lark, and in my relationships with these other organizations, especially Ma-Yi, I get to be in conversation with so many extraordinary writers who I respect and admire, and I get to contribute in some way to what they put out into the world. As someone who believes that cultural expression and social change are absolutely a function of the arts, and that diversity of perspective and a multiplicity of voices are essential to a functioning society, then how lucky am I to make my life's work the amplifying of voices of writers I admire, while using my own work in conversation with it? As part of a really robust community of writing, including Rajiv Joseph, Dominique Morisseau, Kimber Lee, Mona Mansour, Donja Love, Martyna Majok, Rey Pamatmat, Diana Oh, Keith Josef Adkins, Mike Lew, and so many more. Writers who also represent what I want to put out into the world.

Mentorship is a tricky thing that I haven’t quite figured out. I don’t know if I believe in the concept fully. Either I’ve had dozens of mentors or I’ve had none, I’m not sure. Certainly not just one, and I have distrust around mentorship as a singular, centralized force. It seems necessary to me that an artist draw from as many complex and varied sets of influences as possible, so that their voice can become an amalgam of their total, complex identity. That being said, there are definitely a lot of people who have been really instrumental in my life and my career; starting with my family – I write about family a lot, and I draw very heavily on my parents, my wife, my children. Both in terms of tangible support, but also in their bearing. I touched on this earlier, but I think there's a particular aesthetic to being the child of immigrants. It expresses itself in a particular way, with a consciousness towards the convergence of cultures, the creation of something new within something old, a heightened importance on ancestral memory and displaced history. And, as I mentioned before when talking about parenting, there’s something even more powerful about the future tense part of family and the imagining of how young people might move through the world.

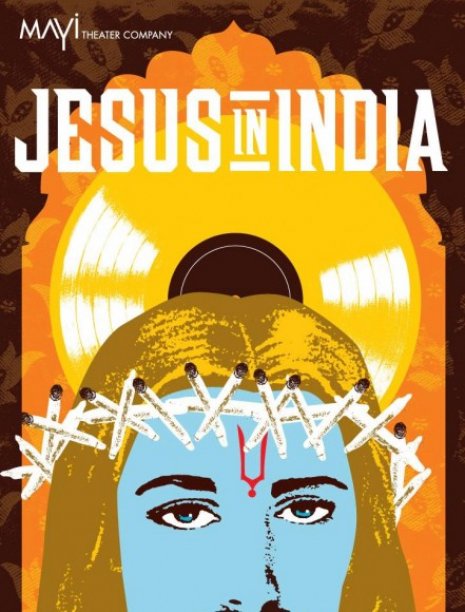

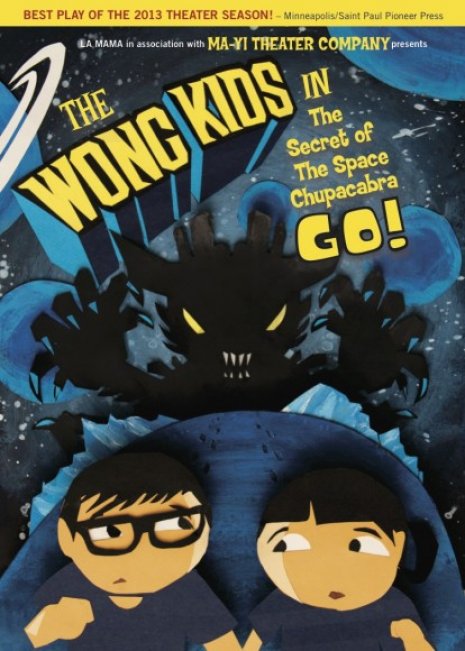

On a professional level, I’ve also been lucky in having some critical relationships with people who have helped me beyond any ability to quantify. You were one of the first people to produce my work, and your support and advocacy have been more critical to my career and my sanity than anyone else in the industry. Not just as a director, and a producer, but as a colleague and a confidant. I mean, let's think about this: I would never have gone to Kenya without you, or had my work done in Manila. You commissioned The Chinese Lady and The Wong Kids, both of which you directed. So you've had a tremendous influence on me, and not just in those very direct ways.

I don't think I've ever said this to you, but I've talked to others before about it. I look at you, and Mia Katigbak, who are artists first and foremost but have also dedicated so much of your energy and time to fostering a community of other artists. Whenever I talk to young theater makers (and I do this a lot), especially young Asian American writers and actors who want advice on how to build a career, I tell them about how you and Mia started your own companies basically out of necessity. It was the only way to get work at the time. You did it your damn self. And the history of Asian American theater is filled with these stories. Young Jean Lee started her own company. Qui Nguyen started Vampire Cowboys. Tisa Chang started Pan Asian Rep, Mako started East West, Frank Chin started the Asian American Theater Company in San Francisco. I definitely don't think that every single Asian American theater maker should start a company, but I do think that they need to know what people like you had to do to get to where you are, and what you still do every day.

Understanding and accessing that history is really powerful. In fact, I guess it's the theme of this whole interview. When I talk about Hoosiers and basement rock shows, I'm also talking about immigration and building a new life in a new country, starting your own theater company, advocating, not just for yourself but being part of a community of artists that are as integral to your life's work as your own individual work. The way I process all of these stimuli is to say: “hey, I'm part of a tradition.” My parents sacrificed a lot, they worked really hard to put me in a position to succeed, and that comes with enormous expectations that are deeply motivating to try and live up to. You and Mia and other pioneers of Asian American theater, you busted your ass for unpredictable and maybe even unexpected glory, and my generation of theater makers better not take that for granted. We have to put our heads down and get to work, to be worthy of what you've done to establish and sustain these critical cultural touchstones. We have to be like underdog punk rock basketball teams going up against the monolith of dominant American culture to say, “hey, we built this country, too, and let's talk about the future, because, dammit, we're gonna build that part as well."

Is that a reach? Maybe. But I don't think it is, honestly.

##########

Ralph B. Peña has been Ma-Yi Theater Company's Artistic Director since 1996, helping to establish Ma-Yi as the country’s leading incubator of new works by Asian American playwrights. Recent directing credits include Lloyd Suh’s The Chinese Lady, Hansol Jung’s Among The Dead, and A. Rey Pamatmat’s House/Rules. His work has been seen on the stages of Ensemble Studio Theater, the Public Theater, Long Wharf Theater, Victory Gardens, Laguna Playhouse, Children’s Theater Company, La Mama ETC, and the Public Theater, to name a few.