Chapter One

Ralph B. Peña, Artistic Director, Ma-Yi Theater Company, interviews Lloyd Suh

Well, for the past several years, almost all of my writing has related in some way to pivotal moments in Asian American history. I like that you ask about what "makes" me write these days, because lately it has felt like an involuntary impulse; I genuinely feel compelled to do it, in a way that's very new to me.

The seed came when I was working on a play called Charles Francis Chan, Jr.'s Exotic Oriental Murder Mystery, which started as an exercise in exploring the beginnings of Asian America as an articulated political and social identity in the late 1960s. The research process for that play led me down some amazing rabbit holes. I had studied as much Asian American history as I could find in college, but there wasn't as much out there as there is now, and pre-internet it could be hard to know where to look to find robust scholarship. But these days, there's a lot more available, and I'll find myself going through various books, and from page to page I'll say hey, there's a play there. There's a play there. There's a play there. That's how I started learning about Afong Moy, which led to The Chinese Lady, and by going into deeper dives inspired by this reading also led to a one-act, Disney & Fujikawa, and now a very large project I'm currently in the early stages of, on the legacy of the Chinese Exclusion Act and the experience of so many hopeful immigrants at Angel Island. There are so many more stories, and now I have this mental list of things I'm interested in going deeper with, to investigate more, and maybe eventually try and dramatize.

As for what it is about that material that's so personally compelling, well, to start there's the obvious: as an Asian American, I'm aware of my lens as an author, and pretty much all good drama leans into the big fundamental questions of who we are and why we're here and where do we come from, all that cosmic and ancestral metaphysical stuff, right? Well, the more I dig into that, and the more I start to interrogate that lens, and my voice, and my place in the grand scheme of things, the more I'm compelled to analyze where it all comes from. Not just as an exercise in excavating the past, because let's face it, a lot of that history is quite bleak and painful. But I'm particularly interested in using the past as a guide to where we come from, so that we can understand where we are now, in relation to that history, and hopefully figure out where to go from there. I try to make it all feel forward-thinking in that way.

To that point, I can't overstate how much of this comes out of parenting. I've got these three kids now, and I wonder what will be different about their experience compared to mine. I'm a child of immigrants. What does it mean to be second generation, or third generation? What will their relationship be to their grandparents' immigration, the legacy they're connected to, of being an American, an Asian American, and all of that? And I guess more importantly, what is my role in it? As a parent, I do what I can to prepare them for the world, and I do my best to prepare the world for what I hope it can be for them. And since I'm a writer, I can't help but think about the utility of my writing in addressing those questions too.

Sure, it means different things to different people, but that seems appropriate to me. Partly because Asian America is a relatively new concept, if not historically then at least as a recognized cultural community in the Americas, and therefore still defining itself. But also because it draws from many cultural traditions and realities; the history and politics of, say, Korean America are different than those of Filipino America, which are different from that of first generation immigrants and those who've been in the States for many generations. Those who grew up like me, in small towns, versus those who grew up in large cities; adoptees, multi-racial children, and all the various intersections with other social identities that have their own cultural traditions. There are parts of it that people can opt into or out of, and many of my peers do just that. But there is absolutely one part you can't opt out of, and that's the way you present in the world. The way you're perceived. And all of that is directly related to cultural stereotyping, and the legislative and economic conditions of our history in this country. And that, to me, is deeply theatrical. In the performing arts, we're confronted with that in a very acute way. An Asian face on stage is significant, and signifying. So as a writer I consider it my job to try and shape how and what it signifies.

It’s funny, I honestly never noticed it in that way before. In some of my work it’s more prevalent than in others, but you’re right, that is something I’ve tended towards. Maybe there’s something about being from Indiana in that too. The whole Hoosiers mythology of the overlooked underdog, going up against the big schools and achieving unlikely glory. That’s pretty ingrained. It’s an unshakably powerful narrative to me.

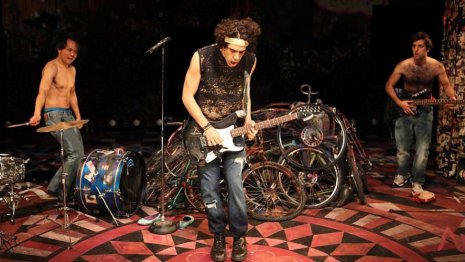

I also grew up in a community that was demographically quite homogenous. In my high school graduating class of over 400 students, there was only one other student of color. So the typical and inevitable sense of angst that’s part of any teenager’s existence was probably compounded in my case. During that time of my life, the place I found the most joy was in writing, in music. I played guitar, and was in some bands in high school and college; we’d practice and write a bunch of songs and then play exactly one show in someone’s basement, then we’d disband and start a completely different band with a new name and new songs (sometimes with the exact same people) and just do it all over again. A lot of these bands were aesthetically very different from each other, but they were all guided by a kind of DIY, post-punk damaged art rock ethos. Even that’s kind of spiritually Hoosiers too, if you really think about it.

I think for a long time my rhythm replicated that sense of starting a band and then moving on to another. Playing around with different sensibilities and styles. Or, if you want to be dramatic about it, trying on different identities. That's just the expression of youth, perhaps. But it's certainly reflected in my early work. American Hwangap is so different than The Wong Kids, which is so different than Jesus in India. Something like Great Wall Story feels like an anomaly, even to me. While there are definitely threads, or themes, or curiosities that track through each of them, I do think the jumping around in form and style was indicative of something unsettled in me. I was searching for something.

I definitely think I'm still searching, but I do think that this history thing I was talking about earlier, it's giving me some ballast. It seems to be a landing place for a deeper dive into a grander theme, and I'm excited to see where it leads me from here.

I definitely don’t consider myself to be a formal experimentalist, even though I’ve messed around with different structures here and there. I’ve always been a big believer in function over form, so any formal experimentation has come out of a storytelling need. With The Chinese Lady, for example, the character made me want to include a bold theatrical gesture; the play is about the audience gaze, and the character is affected by that gaze on a deeply emotional level. I had to foreground her relationship with the audience on a palpable, almost aggressive level. I’d never done anything like it before, and I certainly drew on some other works that handled direct address in similar ways, or navigating historical time with theatrical time: I thought about the opening act of Tony Kushner’s Homebody/Kabul, and I read a lot of Lisa Kron, who has an incredible way of being both intimate and expansive at the same time. And maybe this sounds weird since it has a reputation of being quite old-fashioned, but I also thought a lot about Our Town, which I can’t help but be constantly amazed by, in terms of form and flexibility and impact. How the Stage Manager character can interrupt and appear within the scenes themselves, but mostly exists as a much more knowing figure in the present tense, primarily relating to the audience in that way. Since I was interested both in trying to excavate the past-tense historical character while simultaneously navigating a real-time, theatrical present tense, the eventual form of the final scene in the play organically revealed itself: it became about the act of performing the past, in the present tense. It was a slight inversion of the Stage Manager’s theatrical gesture in Our Town.

That was exciting to me, but sometimes with formal experimentation, I can get lost in the intellectual aspect. I’m not terribly interested in that side of things. I was an English major, I studied postmodern theory and all that, but to be honest it usually leaves me really cold. But there are some writers – like Jackie Sibblies Drury, for example – who manage to use really unexpected formal structures to arrive at a deeply emotional, extremely sincere and impactful place. Jackie does this in We Are Proud to Present, and in Fairview especially. It sneaks up on you, and the form creates a tension that allows for the emotional aspects to land more fully.

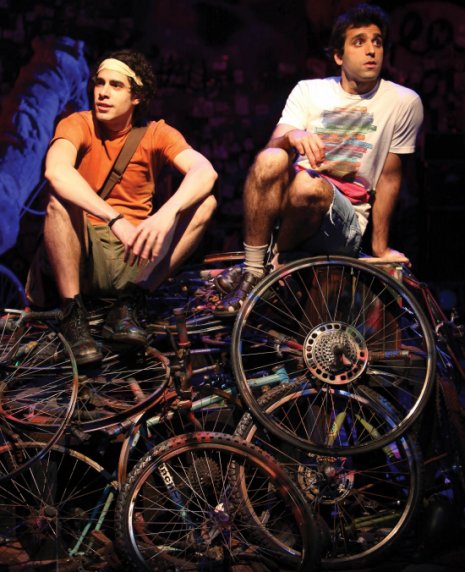

Another trap with formal experimentation is when it starts to feel elitist. Like you’re not smart enough to get it. I hate that kind of stuff. I feel like my biggest obligation is to a cultural conversation, and so form, to me, also follows rules of cultural engagement. In The Wong Kids, for example, the initial formal challenge was in writing a play for young audiences. This was new to me at the time, and so I started with the question: What kind of play would have had the most impact on me, personally, when I was about 10 years old? As I was trying to answer that question, I had so many varied thoughts and ideas, so I just decided I wanted to do all of it. I was writing a play for young Asian American kids who rarely get to see reflections of that identity in the media (and when they do, it’s usually some gross misrepresentation). I knew (a) I wanted to make them heroes, and (b) I wanted to put as much as possible in there, so that they’re reflected in as many different aesthetic contexts as I could imagine. I started to think of it as a type of formal maximalism. I remembered in college I had friends who were Studio Art majors, and one time they got to take over the student gallery space. And so they totally covered the walls. The ceilings, the floor. They covered every inch of the gallery with art. Because for people who don’t often have access, once you get a room you really want to fill it, right? So I said yes to everything. Science fiction. Fairy tales. Naturalism. Puppets. Anime. Horror. A musical number. Some iambic pentameter. All of it. Put it all in there. So the formal shifts that happen in that play are guided by that thematic impulse.

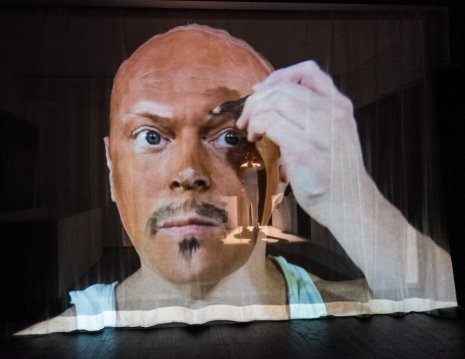

The same thing happened with Charles Francis Chan. I consider that one, at its baseline, straight-up psychological realism. But because it’s about characters using the practice of their art to essay a political and social identity, it had to mirror the impulsive, experimental nature of those characters’ aesthetic sensibilities. Anything in that play that might be called formally experimental came from the characters of Kathy and Frank. I tried to represent the kinds of impulses they might have with respect to theatrical form. The result is way outside of what I was used to doing in terms of structure, and there were definitely times the narrative rules got out of my control, but it felt thematically appropriate for that to happen.