MJ:

Are there core intentionalities - ethically and aesthetically - you seem to re-appear in the work you do, and want to do, for the theater - whether with plays or in performance works or the roles in which you are interested?

TM:

This relates so much to your observation/question about not repeating myself. Yes, it’s absolutely intentional that I try not to repeat myself. Theater makers who work with repetition over their careers, either consciously or unconsciously, tend to do so because they’re trying to figure something out about the theme they’re exploring and the form they use. The theme I’m exploring is heterogeneity. It’s a theme about variation so it makes sense that the body of my work, and the forms I use, are varied. I'm interested in the multifaceted as political and social action.

I think it comes from being an American artist and growing up in a country that professes to be eclectic but champions the singular through a barrage of monotheism, judgment as power, competition, protection, and our polarization. Eclecticism, pastiche, the hybrid and the hodgepodge have become my content, form, aesthetic and practice.

MJ:

You have danced with all kinds of classical work and images, iconic classical literature as well as iconic popular cultural tropes in your work. Can you talk about what draws you to re-examine work such as Greek classics and classic popular songs and whether and how you feel those are related? Also perhaps talk a little about the exploration, deconstruction and reconstruction of identity symbology...including your own?

TM:

Part of my examination and use of older texts, tropes, history and art (usually as inspiration rather than deconstruction or adaptation), comes from a desire to understand craft. The way I can best learn to write and understand the Aristotelian structure—which the content dictated I use in my play “Hir,” among other plays of mine,—is to collaborate with Sophocles. For the Old Comedy structure in “The Fre,” I went to Aristophanes. For the Existential/Commedia mashup I worked with in “The Walk Across America For Mother Earth,” I dove into Chekov, Moliere and Tasso. For the durational aspects of “The Lily’s Revenge,” I spent time with the Noh plays, Beckett, and the Elizabethans. For the Hero’s Journey form and Theater of the Ridiculous style I used in “Red Tide Blooming,” I read up on Joseph Campbell and the works of Charles Ludlum. To learn how to write and interpret popular songs I decided to make a show that deals with the history of them.

What’s interesting and exciting is, now that I've been working this way for a while, I’ve developed a wide-ranging craft (though there’s always some other form or technique to learn.) Another answer to this question is that one of my jobs as a theater artist is to remind the audience of things they have forgotten, dismissed or buried (or that others have buried for them), which means I have to dig up the past and bring it into the present in meaningful ways (in hopes the audience will take that information/experience and do something with it in the future). So it makes sense to use my progenitors to help do that. A third answer to this question is that in making work about heterogeneity, it often becomes a call for and a building/examination of community. I've found that if I want to talk about and/or make community, then it’s helpful if I expose who and what I'm in lineage to.

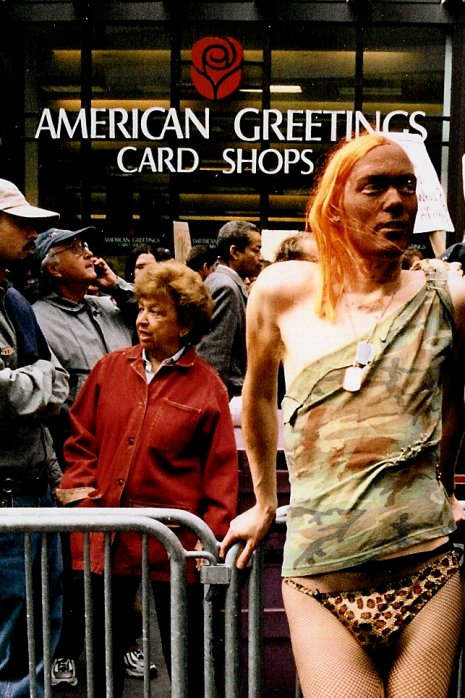

In terms of identity symbology, I work off the Fool a great deal of the time. Basically that means I make work that presents relatable oddities. The goal being: if you can relate to the oddest person(s) in the room then that will bring out more possibility in you.

MJ:

Yes, you have mentioned the idea of “the Fool” a couple of times…the holy Fool, the court jester who can speak truth to power when others can not...Can you talk more about the history and role of the Fool and how that as impacted you as well as perhaps some background on your fascinating world colliding collaboration with Mr. Patinkin?

TM:

Ooooeee I could go on and on about the Fool. I’ll try to keep it succinct. Like most things, the Fool is many things. Historically Fools are almost always depicted as having some heterogeneous quality: between gender binaries; a beggar on the street while at the same time a member of the court. In the tarot and playing cards they are often the least powerful card or the most powerful card and sometimes both. The Fool is sometimes human and other times an anthropomorphic animal; sometimes a simpleton, in other instances wise, blessed and/or possessing divine powers, a philosopher, an insurgent.

Often — especially once the Fool was made more sophisticated by Robert Armin (the actor who played and inspired Shakespeare’s later Fools like Touchstone and Festes and who wrote about the distinctions of Fools in his book, “A Nest of Ninnies,”) — there has become a blurring in our identification of the Fool. Now we see that the Fool is also the Trickster, the cultural hero, and to some degree, the Bouffon. I suppose I’m more in line with Robert Armin’s Fools; I’m drawing on a little bit of it all but leaning more towards Fool as conscious insurgent.

Perhaps the most important aspect of the Fool, at least the one I’m primarily interested in, is that the mask of the Fool was/is used to say the things everyone is thinking but which social etiquette or even law won’t allow you to say, unmasked. Fools get away with it because they’re considered simpletons or oddities that don’t know better. The fun part is that there’s usually a question regarding whether their ignorance is an act. In this way, their weakness becomes their strength. Their outsider status gets them inside. They’re the beggars who end up in the court telling the king he is more a Fool than his Fool. The Fools can do this because their true power lies in juxtaposition: they’re creatures that behave and look uncourtly but who thrive in the court via their uncourtly ways and their ability to speak truth to power.

In my newest play, “The Bourgeois Oligarch,” I address this head on. The vision is we get it performed in an Opera House, where the patrons are wealthy. It’s a comedy (with an edge), so everyone will hopefully laugh and love it, and as a result will listen to the critique that’s in the play (regarding economic disparity), consider, and maybe even adjust their behavior.

(I wonder if Louis the XVI would have altered his behavior and the trajectory of his rule if he had appointed a Fool who would have brought the conversation of greed into the room. Louis the XIV, arguably France’s greatest monarch, had Molière and France’s last appointed Fool, L’Angeli. L’Angeli seemed to be more jester and entrepreneur than Fool but Molière found subtle ways to make the court consider their own greed and unjust behavior.) In my future work I’d like to use the Fool to remind those in power that they only have that power because the people are allowing it. On the flip side I’d like to remind the disenfranchised of their ability to rally, create direct action, and change their lives for the better. I’m trying to figure out a way, in the theater, to do these two things at the same time. What happens when the worlds of the elite and the disenfranchised meet and how is the Fool a sort of subversive go-between? How do we get these compartmentalized people in the room together?

The show I do with Mandy is a reflection of this to some degree but is directed more towards the middle class. It’s vaudeville and vaudeville was made for middle class patrons and is, arguably, the first middle class art form. The wealthy need their satirists and Fools; the middle class need their stand-up comedians and Clowns; the poor need Clowns and Bouffon, and nobody needs the mimes (kidding). Because the middle class is a little silly and want their version of what the upper class has, they bring in the Fools. However, the middle class, in order to get through their days, needs more entertainment and less truth to their power (because they have less power). As a result they water down their Fools and make them Clowns. The distinction: the Clown is there to entertain; the Fool to alter the world through entertainment. Mandy and I, and our collaborators Susan Stroman and Paul Ford, are doing a sort of combo (again with the pastiche work) where we combine the Fool and the Clown. Primarily we’re entertaining but, at the same time, there’s a little poking going on.