Chapter Two

paraSITE began when I was a graduate student at MIT and living in Cambridge, MA. The project moved with me to New York City in the late 1990s/early 2000s, and then, for the past twelve years, to Chicago.

In the winter of 1997, after my first semester at MIT, I participated in an architecture and urban planning workshop in Jordan, part of a collaborative program between the University of Jordan, MIT, and Oxford Brookes Academy. I had a keen interest to visit a place close to where my grandparents had fled. Around the same time I had been looking through a book of photography, documenting Palestinian refugee camps. I believe it was called Intifada: A Way of Life. One photograph showed a Palestinian family standing in front of a structure they had built in the camp: they had recreated the façade of their house in the West Bank - that the Israelis had bulldozed - but built out of recycled materials: plastic bottles, pieces of zinc siding, cardboard, and other detritus. It was a ghost of the original, refusing to disappear; their architecture of resistance.

I felt for the first time the links between the disappearance of Arab Jews from countries across the Middle East and North Africa, and the disappearance of Palestine. Our fates seemed intertwined and I felt an intersecting struggle to remember, to combat amnesia and cultural erasure.

This photograph prompted me to request to visit the Palestinian refugee camps in Jordan, a request that was ultimately denied by the hosting institutions and the government.

When I was refused access to the camps, I ended up spending time near Kerak, Jordan studying Bedouin tents. One of the amazing things I learned was that the tents were set up differently every night, depending on the wind patterns. Positioning the cloth membranes and rigid structural poles to account for something that seems so unpredictable was like the aerodynamics of sailing. It was magic. So I had all this beautiful, poetic data but no idea what to do with any of it.

When I returned to Cambridge in the dead of winter, I saw a homeless man sleeping under the exhaust vent of a building’s [HVAC] heating, ventilation and air-conditioning system. Here was another kind of a wind—a wind that was the byproduct of a building’s service system, recycled, and juxtaposed with another kind of nomadism - urban nomads – homeless people – dispossessed not by tradition like the Bedouin, but by consequence due to a myriad of urban ailments including capitalism and private property.

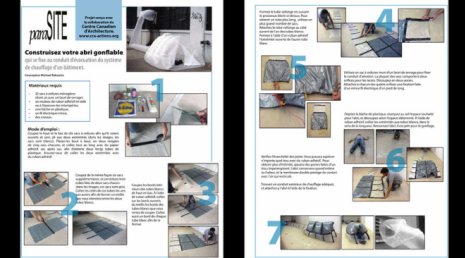

Suddenly I recognized that it was possible to engage with these questions around dispossession and exile without traveling very far. Alienation was in my own back yard. In that moment I decided to harness that invisible air and turn it into something strange and visible and functional. In the project, which has been ongoing for the past 21 years, I custom build inflatable shelters for homeless people that attach to the outtake ducts of a buildings HVAC system so the warm air simultaneously inflates and heats these double membrane structures. The shelters are made on a zero-dollar budget, built from polyethylene rubbish bags that I either heat seal or attach to one another with waterproof packing tape. I was very conscious of continuing the material culture presented in those photos of the reconstructed façade of the demolished Palestinian house.

I was very fortunate to be able to develop this project with input from my mentor Krzysztof Wodiczko, who in 1988 designed the Homeless Vehicle in solidarity with the Tompkins Square Park Riots. As you say, I often work at the intersection of art and design, addressing expectations of utility and function. Thus in my work ‘doing’ has often been a critical moment: art as shelter, art as para-archaeology, art as radical commercial enterprise. In each of these endeavors, however, I am also consciously constructing a kind of failure and critique of problematic mechanisms. Krzysztof calls this particular strategy—one we share—‘scandalizing functionalism.’ It names a place where problem solving is also trouble making. Of course, this trouble is all kinds of things: simply making the homeless visible, people cities constantly try to hide rather than help, and also disseminating the instructions on how to build this shelter should someone need it in an emergency. The step-by-step instructions have been published in different homeless magazines and broadsheets internationally, whether it is The Pavement in London, L’Itinéraire in Montréal or Motz in Berlin.

For the passerby, the project is agitational in its warning: given the availability of these vents on buildings, the readily available materials, and the enormous number of homeless people abandoned in our cities, could we one day wake up and find these encampments engulfing buildings like ivy? It problematizes the problem, but also offers itself as a bandage in that it unflinchingly recycles a thermal waste stream to create kind of architectural CPR, where one building is sustaining another, breathing life into lungs.

The dialogue with each individual for whom I have constructed a shelter has shifted over the years as the homeless population as evolved and grown. In fact, I have used the word intersect a few times in this response already, but I find my projects intersecting now, as many of the homeless people I connect to with this project are now veterans of the Iraq War, who have come back to the US as another kind of refugee. It’s beyond disheartening to see more and more clearly every day just how many people are discarded by neoliberalism and the war culture that bolsters it. But one has to see it.

By now I have engaged with many different homeless communities in different cities, and, from the beginning, I realized that the project was the distillation of the refugee experience into a project that didn’t need to happen in the refugee camps far away, but could connect to them in my own backyard, in my own cities. I did not know the term intersectional at the time, but I could see the personal, the other, the collective in it, and I saw the political, the practical and the poetic operating together.

This project has been so important to me, I constantly learn from it, and I try to keep that engagement with individual people and material culture as a foci in my work. When Joan Jonas came to teach during my last semester at MIT, she deeply affected my practice—I undertook my first performances while studying with her, and it was during a studio visit regarding parasite – which I’ll talk more about later - when she heard me telling the stories of each individual user. She pointed out that that exchange, like the exchange of the air from the building into another one, was a critical moment of the work. Joan told me about the wandering Jew, the accumulation of stories and the importance of storytelling, that it could be transformational. That opened up the rest of my work to me, and I always think back to that moment. That’s where it all emerged from.

When Bergson writes about time, he also writes about duration, about “lasting through.” It makes me think of survival. It also makes me think of sumud, the Arabic word for steadfastness, often applied to the demanded resilience in anti and post-colonial struggles in the Middle East and North Africa. For exercise, my parents were both long distance runners for many years. As a result, I was too, and I learned about endurance as an important skill. I was never fast—in any aspect of my life. But to be able to endure or survive, that seemed like something I could do.

I am interested in psychoanalysis as a form of this kind of endurance, of lasting through as a form of working through. I’ve been in analysis for about four years now, and prior to that, talk therapy for nine years. I never knew what to do with any of the psychoanalytical theory I learned in graduate school in relation to my work. But, being immersed in the process, it makes so much more sense since it is enacting theorems rather than asking for me to only apply them. In my own practice, I’ve tried to create spaces where this kind of return to the trauma does exactly what you said, to learn from it and to heal. To let fearless listening enable fearless speaking.

Coming back to Krzysztof Wodiczko, he would say his first job was to survive; that he knew the initial reaction of people in communities was one of skepticism of an artist who wanted to address their traumas or pain in work. The task of facing rejection with a return for him was essential. How else to communicate his commitment, his sincerity or the fact that he felt something in those places with those people intersect with his own life, his own pain, his own context as a Polish citizen born on the battlegrounds during WWII?

I really am very interested in how we heal, and how it can be done on a broader scale. I do think intimacy is important, even within something that is like a national project, so I’ve been researching the Truth and Reconciliation program in South Africa for many years. In What Dust Will Rise, I was interested in how the material of one cultural trauma, the destruction of the Buddhas of Bamiyan, could attempt to suture the wounds created in another, like the burning of books in the Fridericianum in Kassel, Germany in 1939 and 1941. Placed side by side, we see those materials share physical and historical indexes. Libricide and state-sponsored iconoclasm are characteristic of every war, of every human conquest of one people over another. Symbols of culture were desecrated so that the image was rendered less potent. At the Hessian State Archives, I saw a book of prayers that burned when the Fridericianum was bombed accidentally by the British Royal Air Force. They call it the Halskrause in German because, as a parchment book, it took the form of a neck brace. It burned like human skin would have. When I saw it, it looked like stone, like the book had become petrified from fear. I saw the trauma the book endured.

Coming back to history and Bergson talking about time through something like duration, I am interested in non-linearity, since I do believe this is how our lives happen. I don’t simply tell one story of my work: there are points of intersection, departure, return, tangents, parenthetical incidents, entanglement and minor objects that shape the way things happen. It doesn’t just go away, the same way felt never went away for Beuys. Nothing is ever over.

I think this is why I love a filmmaker like Elia Suleiman. Conclusion is sidestepped in favor of tension. This is the work I want to make. That many of my projects are ongoing is also an indication of sumud. The project doesn’t disappear because the problem hasn’t disappeared.

The notion of disappearance and reappearance is something that I first became fascinated with when looking at the interventionist public art practices of many artists from the 1970s onward. Temporality was so liberating when considering the oppressive permanence insisted upon by so many public monuments that cease communicating directly with its public over time. I’ve often thought that the best way to forget someone is to name a building after them, so their name disappears into an address, into the architecture. I also demand that much of my work haunt and perform as a ghost, like Dar Al Sulh in Dubai, Enemy Kitchen, or paraSITE. Its disappearance is essential in disrupting that notion of time and expectation.

It changes with each project, of course. I think I became aware at an early age of the fact that there was much more to say about artwork than what one initially sees. The research my parents did in preparing trips to museums or sites at home or abroad was considerable. I didn’t have to listen to a tour guide lead a large group, pointing things out; my parents did that, and they did it passionately. It was compelling. Taking boring art history courses years later in college, I realized that one is always at the mercy of the narrator or storyteller.

I mentioned before how Joan Jonas opened up the space for me to tell stories in my work, and without this interaction, I am not sure I’d be making the work I am right now. It felt like an embrace of something more magical or even shamanistic than explanatory. Fast forward a couple of years to 2000 when I first saw Walid Raad give a performative lecture in the context of his Atlas Group project, and that was it. Only, for me, I was more interested in the unbelievable stories that I was uncovering through obsessive research, instead of fiction.

The public artists who were so dear to me, like Hans Haacke, Mierle Laderman Ukeles, and Gordon Matta-Clark, made and make work that is experiential and deeply social. When that work is presented as a document, it is images and stories that we are left with. I liken this to the live album. I love concert recordings of my favorite musical artists because it collapses the space of the performer and the audience into one. We never listen to Jimi Hendrix’s studio version of the Star Spangled Banner, we listen to the one from Woodstock, where you can hear it all—the Civil Rights movement, Vietnam, MLK’s assassination, it’s all in there. I like the raw unmediated quality of those moments even if I could never live them when they happened. I feel that way about “A Day in the life of FOOD”, a film documenting Carole Gooden, Gordon Matta-Clark and Tina Girouard’s experimental restaurant.

I believe that great books need great readers. Works that are expansive and decentralized require the same expanse and slowness from its viewers. Again, this is about duration, and in a world where everything we look at or read or hear is delivered in the fastest form, I see anything that cannot be reduced to a sound bite or a tweet as a victory for complexity.

Teaching has had an impact on my work, as in the way I have presented ideas and art to my students. I remember trying to put together slide lectures so as to expand on topics in unexpected ways, connecting seemingly disparate objects and events. In a lecture I gave on design and social responsibility, in 2002, to illustrate the impact designers had on our lived experience and on history, I opened with an image of the Pruitt-Igoe housing units being imploded in 1972, the very moment that Charles Jencks located as the threshold where modernism ended and post-modernism began. Minoru Yamasaki designed the buildings and before the Housing Act of 1949 had been compromised by the time the buildings opened in the mid-1950s, many of its features that were supposed to enable safe, democratic living had been done away with. The last slide of this rangy lecture that included examples of artists, designers and activists like Temporary Services, Marjetica Potrč, Shigeru Ban, and Architecture for Humanity, showed Yamasaki responding to the demolition of Pruitt-Igoe on the site of his new building project: the World Trade Center. The lecture ended on that note, with gravity but a question lingered in the air: if the demolition of Pruitt-Igoe in 1972 marked the death of the dream of safe, democratic living, then what did the collapse of the World Trade Center mark?

This lecture would later evolve into my first gallery exhibition, titled Dull Roar (2005) at Lombard Freid Projects in New York City. Working in a more institutional setting, I relished working site specifically, thinking about things like accession cards and the indexing of information that could be derived in the written text in architectural proposal sketches, which always reminded me of the storyboard drawings for movies. I made a suite of drawing scrolls that connected the seemingly disparate collapses of buildings, people and ideas from 1972 onward, a story of entanglements that pushed back on the possibility of mere coincidence and made use of the claustrophobia of conspiracy theories.

These drawings are always complicated by the objects around them, whether in this case with the inflating and deflating model of Pruitt-Igoe, or the valuable design artifacts— like the Hoover 150, the model designed by Henry Dreyfuss, the tube of which he used to commit suicide by carbon monoxide poisoning in 1972—presented not in vitrines but mobilized in kinetic bricolage sculptures. I want those diversions and ruptures that I love experiencing in non-linear post-modern novels to affect the cadence of my work and the space in which it is shown.

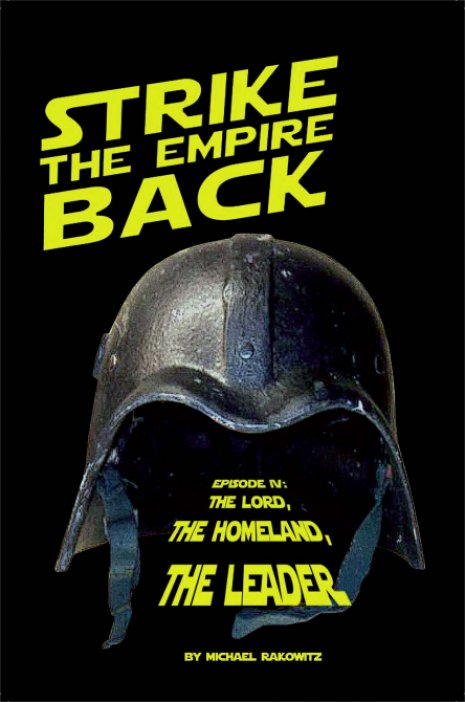

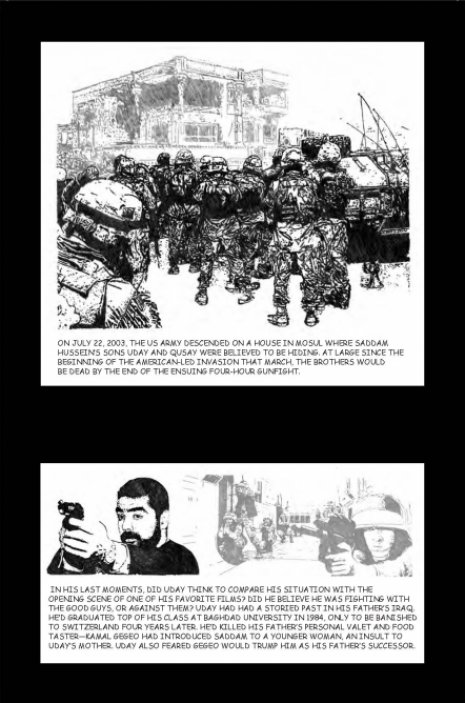

Storytelling was the only way to present that project! The worst condition is to pass under a sword which is not one’s own followed on the narrative of The invisible enemy should not exist which I’d begun two years earlier. One of the details of the research in that project was learning where the looted artifacts had first ended up being trafficked. Aside from places like Christie’s or other auction houses, some had shown up on eBay. By 2007, it was nearly impossible to find a Mesopotamian artifact on the auction site since it had been so heavily monitored. Still, I set up an alert to be notified whenever anything from Iraq had been posted. Needless to say, I received many notifications per day. But one morning in late 2007, a listing showed up in my inbox for an “Iraqi Fedayeen Saddam Darth Vader helmet.” The seller was a US soldier in the 101st Airborne Division based in Mosul, Iraq. It was uncanny, and looked like it could have been cast directly from the top helmet portion of the mass-produced costume of the Star Wars villain. In the listing, the seller’s description indicated that these helmets were worn by the Fedayeen, among the last of the Iraqi forces to fall, and it was described as ‘surreal’ to see the cinematic personification of evil shooting back at US forces. The text continued that, when questioned about this, the local population revealed that Saddam and Uday were huge Star Wars fans, and when his father asked him to design the uniforms of the Fedayeen in 1995, Uday chose to dress them in helmets based directly on Darth Vader. No news outlets were reporting on this. It was a minor object. But for me, this was a form beyond embedded journalism. I found it fascinating, and knew that there was a story here: after being the US’s proto-ally against Iran, Iraq invaded Kuwait, falling from grace, ‘turning to the dark side.’ It was almost as if the leadership said, this is what they think of us? Then we’ll wear the uniform. Since this project, eBay has become my search engine of choice.

I knew however that one object was a curiosity. I wanted more. Going through my newspaper archives from the Iraq War, I found those Daily News covers from April 2003, just days after the Iraq Museum was looted. As US forces entered Saddam’s palaces, the tabloids referred to them as Shag-dad love pads. Describing the artwork, the Daily News wrote: “The artwork hanging on the walls wouldn't be out of place on the cover of a romance paperback. One airbrushed painting depicted a bare-breasted blond sidling up to a fang-toothed green demon.” In fact, many of these artworks were the covers of fantasy paperbacks like King Dragon and were painted by US artist Rowena Morrill. Her close friend, artist and illustrator Boris Vallejo wrote the essay in her monograph, and also painted the Empire Strikes Back poster that hung on my wall in my childhood, depicting the protagonists of the story with a large figure of Darth Vader looming in the background, wielding to light sabers over his head—in the same way that the Victory Arch would; a colossal monument in Baghdad that was erected in 1989, depicting Saddam’s hands wielding the swords of Qadissiyyah, to celebrate Iraq’s victory over Iran during the war. Then, in 2008, I heard the Iraqi art historian Dr. Nada Shabout give a talk on Iraqi art. She explained that on the eve of the first Gulf War in 1991, Saddam held a military parade during which the Iraqi Army marched under the victory arch to the theme song from Star Wars played over and over again. That was it. I had my story.

Of course, I wanted to push further and found the connections more widespread, as many of the weapons developed under Saddam were made by people like rocket scientist Gerald Bull who became who he was because of an early childhood exposure to the science fiction works of Jules Verne. I dug into whatever forensic speculation I could get my hands on to determine when Uday would have seen Star Wars with his father. I was struck by the fact that had he lived, Uday would have been the first dictator from that generation raised on Star Wars. Did he play the same games I did in my backyard? Did he pretend he was Luke Skywalker, like I did? I wanted those thoughts to open up into the project, and so they do, in comic book-like moments rendered in drawings that were turned into an actual, physical comic book distributed by the Tate. I recognized that there was so much information in the project, possibly too much for one viewing, and so I wanted something to go home with the visitor, to extend the space of the artwork, to be slowly digested at a later date.

The objects in the vitrines, the drawings, the sculptures all try to distill through material culture and provenance this story, and to make tangible the feedback loop between our cultural consumption and geopolitics.

I mentioned earlier in our conversation what ‘doing’ constitutes in my work. Being an artist who seeks to attach to other professions but without orthodoxy as I’ve done with architecture, archaeology or international. In 2006, the sustainable architect Tony Fry told me that this approach was illustrative of what he calls ‘redirective practice,’ a cultural practice bridging disciplines and aiming toward ethical directional change. The move beyond disciplinary confinement can yield dramatic results, and for me this is always rooted in some form of failure, often camouflaged by layers of efficacy. So, in the instance of RETURN, many importers-exporters reached out to me to offer help and advocacy. The oppressive trade restrictions to this day prove too monolithic and quite frankly corrupt to have yielded much change, but to this day I still get inquiries from importers on how to make this import happen as real life and not art. During the project’s run, in 2006, I heard from soldiers stationed in Iraq, many of whom had agricultural backgrounds here in the US and saw what happened to the date groves in Iraq as a result of the war. They wanted to find some way to help, to find some way of rebuilding part of Iraq in the midst of a war where they felt they contributed to the destruction of entire society and land.

What Dust Will Rise involved Bert Praxenthaler of UNESCO and Afghani sculptor Abbas Allah Dad as collaborators in teaching the stone-carving workshops in Bamiyan. On one of the last days of the workshop, Abbas mentioned how he’d always dreamed, since the Buddhas were destroyed, of opening a stone-carving atelier in Bamiyan to teach the skills to a new generation of people. He doubted it would be of interest to local young people, but the workshop showed him otherwise. The next day, he met with the local Governor Habiba Sorabi who granted him land on which to build his studio.

With Enemy Kitchen, I’d say the best illustration of how the project evolves beyond the art world is the fact that the truck rolls up and for many, this is a strange moment of both hospitality and hostility. The Iraqi refugee chefs and the sous chefs and servers, comprised of former combat veterans, have in some cases collaborated on separate projects. It’s also a project that has helped me forge relationships with chefs and people in the culinary arts, like Alice Waters or Claudia Roden, both of whom I am collaborating with. The alignment of food politics, food justice, and the compilation of endangered or dispossessed recipes with my practice enriches the work and broadens the audiences I am reaching.

I am also moved by the status of the food truck here in Chicago. I began working with a small restaurant run by Iraqi Assyrian chefs called Milo’s Pita Place that advertised itself as Mediterranean Cuisine. As we know, Iraq does not have a Mediterranean coastline. But, as with most Iraqi restaurants in Chicago, they do not feel safe disclosing where they are really from. However, Iraqi dishes like masgouf on the menu are dead giveaways. As a result of the coverage and success of the food truck, Milo’s became very busy. And as a result, the family who owned it had the chance to do what they always wanted to do which was to open up an Iraqi nightclub. So, Milo’s Pita Place became Milo’s Palace, they moved to a bigger location, and ever since then have not had the time to bring the food truck out on the road. They hire musicians, some of whom are newly arrived refugees to play on Friday and Saturday nights. They’ve even come out of the closet a bit with their name: last year, Milo’s Palace changed its name to Babylon Bistro.

So, it was a food truck that became a nightclub. Instead of sustainability, there is evolution. Like compost.

Teaching does many things in my work. As I mentioned before, it opened up a space of storytelling that I did not know would follow me back to my studio. I think it has also forced me to ask myself the same hard questions I ask my students. After all, in the best sense, teaching is having robust, difficult conversations with young artists about their work. I try to address those same issues in my own work.

Teaching has also afforded me the ability to make the work I believe in without relying on the art market. I think I’ve heard Hans Haacke talk about this in the context of his own career, receiving guidance from Leon Golub, who suffered from the precarious fickleness of the art market. I believe he told Hans that teaching was not only inspiring but smart, since it provided a living and afforded a freedom to create what one believed in.

I am grateful to every teacher that shaped my work and me: Dennis Adams, Joan Jonas, Alison Sky, Allan Wexler, Krzysztof Wodiczko, etc. I teach because I love the way I was taught. I feel a responsibility to pass on every opportunity and possibility created for me to my students.

*****

Cecilia Fajardo-Hill is a British/ Venezuelan art historian and curator in modern and contemporary art

Fajardo-Hill holds a PhD in Art History from the University of Essex, England, and an MA in 20th Century Art History from the Courtauld Institute of Art, London, England. As curator and art historian she focuses on artists and areas which have been suppressed because of a continued history of colonialism and patriarchalism. Recent projects include Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960-1985, 2017-2018, Hammer Museum, Brooklyn Museum and Pinacoteca; the co-editing of a 20-21st century book on Guatemalan art (forthcoming); and the platform abstractioninaction.com