Chapter One

This email conversation between Michael Rakowitz (traveling between Chicago, and London) and Cecilia Fajardo-Hill*, (in Los Angeles, Ecuador, and Brooklyn) took place between March 6 and April 26, 2018.

I began my art education as a stone carver in high school in the summer of 1990 at the height of the culture wars. I understood the political frame in which that all happened, and, as a 16-year-old, also understood that the work, that the debate, vilification, and the simultaneous reverence for the work extended the space that it occupied; that is to say, a Mapplethorpe or Serrano photograph was not relegated to being experienced only in the gallery or museum space where it hung, it was dispersed into the streets, newspapers and airwaves that it agitated. At this age, I had the luck to travel to Florence with my parents and brothers and learned of similar controversies that unfolded around Savonarola’s reign in that city in the late 15th century. It was his followers who organized a bonfire of the vanities in 1497 that included musical instruments, books, artworks, scores, etc. It was under his rule that a campaign to rid the city of vice began, and laws against sodomy, public drunkenness and adultery were passed. The 1490s sounded a lot like the 1990s. It made me think of history as a continuous struggle against these ambitions of purity.

All this said, I embarked on my studies in art school wanting the work I made to speak for itself, to not enlist explicit content as a tool, but rather to exercise restraint. In fact, I began college as a graphic designer, since that seemed a way to ensure job placement after graduation, but it also allowed for content to be embodied in abstraction, the multiple and access. Printed media excited me as a site of public art.

But it was when I was studying with a minimalist sculptor in my freshman year that a lot of pertinent questions about what to say and how to say it arose. Tal Streeter was a very special teacher in this way, and while he did not disavow work that was political and personal, he was skeptical of when and how artists deployed these layers of content. The following year, I studied with Allan Wexler, who opened up my mind to how architecture and design might merge with art. He is a Jewish architect and artist, and embodied everything I ever wanted to be as a human and as an artist. He made amazingly simple yet complex vessels for mundane objects. He made me understand the Passover Seder as ritual, and as something that shared a kinship with performance art and the writings of Yoko Ono or Duchamp’s reciprocal readymades. It was while working with Allan that I first experimented with distilling my Jewish experience into my work, or combining seemingly unlikely connections between things, like eating and baseball.

I felt a lot less rigid in my thinking and more liberated after working with Allan, and transitioned from being a graphic design major to being a sculptor. After working with Alison Sky and SITE, I was wholly dedicated to public art and architecture, and it was fortuitous that MIT offered a Public Art graduate program in the Department of Architecture. There I studied with Dennis Adams and Krzysztof Wodiczko who conveyed the importance of social engagement in making work for citizens, not just cities. This was a struggle, as I never wanted to make work with overt, hollow, sloganeering messages. Krzysztof operates so beautifully and ethically across communities, and made us as students understand that crisis is not simply handed out at the door; as artists and as people, we needed to explore deeply where we were truly intersecting with what was happening in the world around us, to be aware of one’s privilege, to not exploit or instrumentalize, but to not be afraid to scandalize.

(1) André Lepecki, Singularities: Dance in the Age of Performance, London and New York: Routledge, 2016 pp. 2-8.

I think it is a very meaningful way of thinking about my work, and I thank you for bringing Lepecki’s work and Huberman’s quote to my attention, neither of which I was familiar with, but with which I feel an instantaneous connection and kinship.

I don’t set out to simply counter colonial meta-narratives, but I am aware that I do this. I think this comes from wanting answers to very specific questions: why can’t dates from Iraq be imported into the US after the UN sanctions were lifted? Why did no media outlet report on the fascinating influence of western science fiction on the design of the weapons, monuments and uniforms in Saddam Hussein’s Iraq? Why has no one asked what Palestinians thought of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, which was released just days before the Six-Day War in 1967? Why are there no Iraqi restaurants in New York? Why can I no longer find Mesopotamian artifacts for sale on eBay, but I can buy a plate belonging to Saddam Hussein with ease? Why isn’t that being monitored, and why doesn’t Iraq want it back? And so on. These questions do indeed excavate neo-colonialist and racist foundations in our government, especially enacted through US foreign policy in the Middle East.

But I try to do a number of things in my work, not any one thing, and much of this becomes clear once I’ve made the work. In the case of some of the open-systems I create, in projects like RETURN (2006), Enemy Kitchen (2003-ongoing), or Spoils (2011), the dismantling of neo-liberal conditioning and the strangeness unfolds along the way. Those ‘unanticipated swerves’ and the things that happen to the work, to the public that produces meaning around the work, and to me decenters the work and points vectors at multiple episodes, stories and events which makes it hard to reduce the projects to any one discrete object or summary. Spoils was a culinary intervention in collaboration with Chef Kevin Lasko at Park Avenue Autumn in New York City, featuring venison atop Iraqi date syrup and tahini (debes wa’rashi), and served on plates looted from Saddam Hussein’s palaces. The plates were purchased on eBay from two different sources: an active American soldier serving in the 1st Brigade, 4th Infantry Division—the same unit that captured Saddam Hussein—and an Iraqi refugee now living in Michigan. The project culminated in the repatriation of the former Iraqi President’s flatware to the Republic of Iraq at the behest of current Prime Minister Nuri Al Maliki on December 15, 2011—the date Coalition Forces left Iraq. I could never have predicted these detours, which made the project so much more meaningful in the way it mirrored the repatriation of ancient Iraqi artifacts looted from the National Museum in 2003, but it also was a very interesting and powerful critique that, at the end of the US’ “nation building” project in Iraq, it was the symbols of Saddam Hussein that the regime wanted back to mark its sovereignty.

I think projects like this illustrate the criticality I bring to the institution of art and its conditionings—it makes the work hard to collect, and hard to represent as a whole after it has happened and has expanded to include objects, stories, documents, rumors, smell, taste, encounter and perhaps even ineffable sensual experiences.

I’d say the complexity of the work happened over time. While I do think some of the earlier projects like paraSITE and RISE (2001) had simple, perhaps more concise centers, it was the spillage into storytelling that really created a more layered and expanded approach. If I think back to how and why this happened, it might have a lot to do with seeing the films of Palestinian director Elia Suleiman who delightfully slowed down narrative for me, made me appreciate repetition, and whose films had a mischievous and poignant humor that resonated within me. This happened around 2001, at 16 Beaver Street in NYC. It would also have a lot to do with attending some of the sessions that summer during which Emily Jacir hosted people in her studio to embroider on a UN refugee tent the names of the 418 Palestinian villages that were depopulated, dispossessed and destroyed—the dispersal of the act of making that work collectively and remembering the Arabic music performed in her studio, the conversations, and social space added aura to that project, and it is something Emily makes clear in the work. It cannot be reduced simply to a tent.

I also think meeting and falling in love with my wife, Lori Waxman, gave the work more complexity. Not only did she, as a critic, open me up to seeing much more work, but also introduced me to the post-modern novel. When we met, I began reading Underworld by Don Delillo. It made me think of Walid Raad’s incredible lectures and exhibitions. The non-linear aspect of the narrative, its length, and the concentration on the holy, minor object (the baseball that Bobby Thomson hit for the game-winning home run in 1951 that launched the NY Giants into the World Series) as a means to tell a story was very attractive to me, especially as an obsessive collector of baseball and Beatles memorabilia and knowledge. The unreliable narrator who would appear in books by Jonathan Safran Foer and the breadth and ranginess of David Foster Wallace really brought the literary into my work, as well as the singularity. I was unafraid of subjectivity and the idiosyncratic. paraSITE never responded to statistics regarding the homeless population, but the individual needs and desires of each homeless person. In this way, the singularity could approach the collective and gave it a less unwieldy, less abstract body.

On a personal level, the Middle East was always there in my house in the Arabic spoken by my mother with her parents, in the food, in the objects like the carpets my grandparents were able to bring with them from Iraq, in the artwork, and in the music. Most importantly, it was in the customs and the hospitality. It was all normal. In my very early childhood, it was where I was from. My father’s family emigrated from Eastern Europe via Palestine, and so there was also an Ashkenazi half, but as I grew up in my maternal grandparents’ house, Iraq was the dominant and most present culture.

I only became aware of the politics of the Middle East around the time I turned eight or nine years old. The Iran-Iraq War began, Sadat was assassinated, and Israel invaded Lebanon. I remember playing two-on-two basketball against the Persian Jews in Great Neck where I grew up, and the other Iraqi Jewish kid in my school, Albert Murad, and I lost, and we shot back, “well, we’re winning the war.” It was a culture that was being slowly vulgarized and dehumanized.

I never expected what would happen almost ten years later. We had been in Jerusalem for the first time during the summer of 1990, right after Iraq invaded Kuwait. We were there for my younger brother’s bar mitzvah. One of the highlights was walking through the city with my mother, who conversed in Arabic with shopkeepers and passersby. It demystified a seemingly unapproachable rift that was painted by the media as Arab vs. Jew. Here I understood the Arab-Jew that my mother was, that seeped into my own DNA. Ella Shohat refers to the hyphen in Arab-Jew as a bridge, allowing a ‘re-membering’ of this identity that disappeared in the Middle East after 1948 along with Palestine and Palestinian identity.

This visit made it all the more real for me when, in January 1991, I witnessed Iraq for the first time in real time via CNN’s green-tinted images—night-vision—of buildings in Iraq I would never get to visit, being blown up by American bombs. Suddenly, there at the dinner table, watching all this unfold, I realized that the place my grandparents fled to was destroying the place they fled from. I felt bifurcated, shattered.

My mother saw how this was affecting me, and got my brothers’ and my attention, distracting us from the TV. “Do you know there are no Iraqi restaurants in New York?” she said. It was like a riddle from the Sphinx. Later, I understood what she meant: that Iraq was not visible in this country beyond oil and war. That moment would serve as a primal scene that inspired Enemy Kitchen as the drum once again began to beat toward war with Iraq in 2003.

Enemy Kitchen also identifies a bit of a shift in my work where, as opposed to paraSITE, there is a more direct and explicit relationship to content. The reasons for this are multifold, but also fairly simple when one considers that the stakes had been raised by the invasion of Iraq, and I’d already been galvanized as a result of my personal interactions with artists and poets from Palestine, Armenia, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Egypt and Iraq. When people I cared about were in the line of fire during Israeli incursions into Ramallah, or people I was working with were displaced from Iraq during the insurgency that followed the war, it seemed art was a place that could create facts that were not being told, that were suppressed by a dominant western narrative. It also comes through in my teaching where students experience work by artists from this region and hear another side to a story that is not made readily available to them.

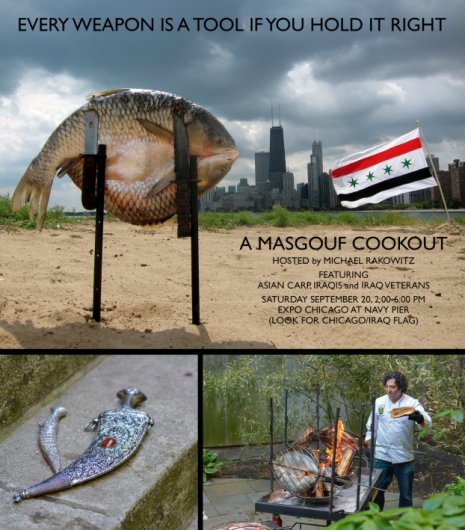

My reaction to all this, however, has not simply been to recreate the wounds of the war, but to suture them, to humanize these places by telling the stories that haven’t been told in unexpected ways, of allowing the disappeared to come back, but differently as a ghost. Enemy Kitchen makes Iraqi culture visible in the US beyond war to produce an alternative discourse and social space. Helped by my Iraqi-Jewish mother, I teach Baghdadi recipes to audiences, including students at NYC’s Hudson Guild Community Center in 2006, where many of the students had relatives serving in Iraq, but few outlets to discuss the war. In 2012, Enemy Kitchen evolved to include a food truck in Chicago, with Iraqi refugee chefs and Iraq War veterans taking orders as sous-chefs and servers, thereby inverting the power dynamic of the war.

This project also evolved to include a related culinary encounter titled Dar Al Sulh (2013-ongoing) in Dubai that was the first Iraqi-Jewish restaurant to open in the Arab world in over 80 years. The surfaces upon which the dinners were served are from Jewish families who left Iraq in the ‘40s and ‘50s as well as trays used in the Great Synagogue of Baghdad. The project also sought to mobilize things like shared cooking traditions between Muslims, Christians and Jews in Iraq to undo the myth of Iraqi Jewish cooking and to point to the close relationships between those communities before it became popular to point out the differences. To show the past of a place like Baghdad as a pluralistic, multicultural city not as nostalgia but as a blueprint for how things could be.

It is also important to mention that I taught at the International Art Academy of Palestine on numerous occasions at the invitation of Emily Jacir and Dr. Tina Sherwell, and this has created a very intimate and generative relationship with the art being made by a young generation of artists living under occupation, which has informed my teaching and my own work.

Growing up as an American and Iraqi didn’t hit me until, like I said, I was in high school and the Iraq War began and I was split down the middle. The experience of being Iraqi was one that I initially just thought was what it meant to be Jewish, since the big feasts that accompanied family celebrations usually happened around holidays like Rosh Hashanah, Passover and weddings.

I listened to my grandmother, Renée, tell stories of a city that sounded wondrous to my very young ears. In Baghdad, there was a scorpion that lived in their basement. There were towers that ‘sang’ the time. At age six, I had trouble with numbers and reading a clock, so a tower that sang the time sounded great. I later realized she was talking about the minarets, and for her as a Jew, this was not a religious sound, but a secular one, part of public space. So, if she heard the adhan, or the call to prayer for the third time in a day, it meant that she had better get to the market because they would be closing by the fourth call.

Many Jews fleeing the Islamic Revolution in Iran settled in the town I grew up in on Long Island in the late 1970s and 1980s. By this time, a significant portion of the Iraqi population that had arrived with my grandparents and after them had moved away or passed on. Still a largely Jewish town, Great Neck was predominantly Ashkenazi, and so there was a tension between the ‘Americanized’ Jewish population and the newly arrived Persian Jews. No doubt, this had a lot to do with prejudice and ignorance that still pervades US attitudes toward the Middle East, as you mention. It did not help that the rhetoric and reporting on the toppling of the Shah or the hostage crisis painted a picture only of lunacy and lacked any critical reflection on why this was happening or explored nuance. The public discussion as I remember it made no acknowledgement of the Shah’s brutality, his human rights violations, or the oppression of the working class in Iran. Coupling this with the way the Palestinian struggle against the Israeli occupation was reported and conveyed in Hebrew school made it seem as though World War II never ended.

I also remember the popular culture at the time made little space for counter narratives and looking back one sees how propagandistic it was. The evil Arab antagonists in the Delta Force movies, Rambo, all readily and earnestly consumed by 11-year-old boys like me. I internalized this, didn’t think twice, but didn’t realize the irony that it was actually half of me and my identity that was being lampooned, caricatured, and dehumanized.

When my family visited Jerusalem for the first time in 1990, I realized what transformed me was that I was visiting Palestine, not Israel, as I thought. What made me feel connected, what made me feel like I was home, was hearing my mother speak Arabic again, for the first time since my grandmother died six years before. What felt like me was the intimate hospitality, the food, the music. I remember a tour guide bringing us to the YMCA tower in West Jerusalem and telling us we could see into Jordan. I took my mother’s camera, with the telephoto lens and kept zooming in, hoping I could zoom past Jordan and see into Iraq. I finally knew who I was.

This moment intersects with another from further back the past. When I was six years old, my mother read to me children’s books about the American Buffalo and their disappearance due to a century of over-hunting by white settlers. The allegory of these narratives spoke to the disappearance of Native Americans, who themselves were hunted by the white settlers, and displaced. My mother would weep while reading these stories, and from this early age, I understood the profundity of art—these stories showed how powerful words were when wielded creatively, in this case marking what was no longer there with what remained. I became committed to articulating absences and voids, and fighting against disappearance and the institution of amnesia.

I thought of this moment from my childhood when, at university, I first encountered the Palestinian narrative of their Nakba (disaster) in 1948, and I processed it as an indigenous struggle for human rights, and against disappearance. I could not reconcile the Zionist quotation of the spiritual return, which heralded ‘an ingathering of exiles.’ (Deuteronomy 30:1-5; the biblical promise of Israel sometimes cited in early Zionist positions). An ingathering of exiles to create new ones seemed horribly unjust.

But you also asked me how all this informs a critique of institutionality, so let’s talk about another moment with my mother, who clearly has been the biggest influence on me as an artist. At age 10, we travelled to London only two months after my grandmother passed away. She was our last link in our immediate family to Iraq, and we went to visit my Uncle Niyazi and my Auntie Tiffeh, who emigrated from Iraq at the same time as my grandparents, but decided to settle in London. The visit allowed us to reconnect with family and cross another bridge back in time to Baghdad. During our visit, my parents took my brothers and me to the British Museum where we visited the Assyrian Lion Hunt friezes, or The Lion Hunt of Ashurbanipal. In that room, sitting on a bench and looking with wonder at the carved panels, my mother told me that each carving was sequential, and that made this work from the 7th Century BCE the oldest comic book in the world. Then she told me it came from the place that she and my grandparents came from—modern day Iraq. I immediately wondered what it was doing in London. This was the moment when I really began questioning the authority and the very foundations of the Western imperial or encyclopedic museum. I wondered, did the museums in Baghdad have a piece of Stonehenge in exchange for these relics from Nineveh?

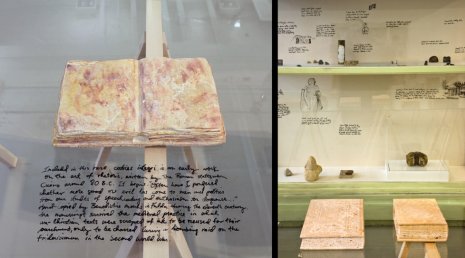

These asymmetric relationships would become all the more focused in projects like The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist (2006-ongoing), which unfolds as an intricate narrative about artifacts stolen from the National Museum of Iraq during the 2003 US invasion, including colonial history, related events and unexpected protagonists. The centerpiece is an ongoing series of sculptures that attempts to reconstruct, life-size, the 7000+ looted archeological artifacts from Middle Eastern food packaging and Arab-American newspapers. I understood the looting of the Iraq Museum in April 2003 as something that happened as a result of the insatiable global antiquities market, largely created by museums and collectors in the west, and that for so many people this was their ticket out of the country, a liquidation of the past to save their future. At the same time, I try not to focus on low hanging fruit and want to understand the complicated, messy ethics of a situation.

I worked closely on this project with Dr. Donny George Youkhanna, the former Director General of the Iraq Museum and President of the State Board of Antiquities and Heritage who was responsible for the recovery of more than half of the 15,000 missing artifacts. He told amazing stories about the works. Some are replicated as quotes contained within the accession cards that accompany artifacts displayed within this ongoing project.

This piece has a very nice story. It was taken by two young men during the looting—they took nine very nice pieces to their houses. They came to us after the looting and they said, "Don't ask for our names or addresses. We were in the museum at the time of the looting. We felt very sorry because we could not stop anything." Then they decided they would take things and bring them back when it was safe. And they did it. As soon as we had the American soldiers protecting the museum, they brought back the nine pieces. —Dr. Donny George

I was also very interested in the discomfort I felt when he told me the quote below, reproduced among the accession cards. It seemed almost like a justification for the plunder of Iraq’s cultural patrimony by the west.

Immediately following the looting, I heard of Iraqis in London who visited Room 56 in the British Museum to make sure something of their heritage was left. Before that, they were critical of the museum for housing things they felt belonged back in Iraq. Now, knowing they themselves could never go back, those objects were no longer contested in their view but were refugees, and safe, like them. —Dr. Donny George

As for my attempt to restitute a collective memory, I think you’ve touched on exactly all that can ever be: an attempt. So often I find I am working with fragments and with memories that have been suppressed so long they have disappeared. But if we are to take perhaps Dar Al Sulh as an example, my 2013 extension of Enemy Kitchen in Dubai, which I made in collaboration with Ella Shohat and Regine Basha, the desire was to open the first Iraqi Jewish restaurant in the Arab world as a ghost. Some forgotten recipes were cooked for diners who included Palestinians, Syrians, Emiratis, Iraqis, and other foreigners. What Iraqis in Dubai remembered was what every narrative said they forgot. They remembered their Jewish neighbors in Baghdad, they missed them, they wept when the political situation got so out of control that families felt forced to depart. Living through the moment we are living in now in the US, one can see how nations can get to this point, where there is an overarching feeling of hostility at the government level despite the will of the people. Stories of how Christian and Muslim neighbors protected their Jewish neighbors from angry throngs during the 1941 farhud or violent dispossession against the Jews, were resurrected, and while no photos of these acts of care exist, I framed one photo in the restaurant that Emily Jacir sent to me: Palestinian militiamen protecting the Magen Abraham Synagogue in downtown Beirut from attacks during the Lebanese Civil War in 1975. For me, that photo is one of those stories that went undocumented.

The plates used during the dinner were metal platters smuggled out of Iraq by the Jews who left in the 1950s and 60s that I have collected or have been given over the years. Instead of them resting like corpses under a vitrine, as many argue they should, we used them, and so our hosts were ghosts, appearing as apparitions that could point the way to a return of belonging.

Could "What Dust Will Rise," (2012), which helped revive stone carving as a craft in the Bamiyan Valley after a nearly 300-year absence be such an example? I'm interested in understanding how this notion/intent is imbedded conceptually and symbolically in your art processes.

My wife’s illness really brought into sharper focus in a more personal space what I was already doing in addressing these issues, sometimes in places that are very far away. In those moments following diagnosis, when all the questions—those awful questions one asks about the future—were being asked, there is such a painful, desperate desire for immediate healing. And of course, it’s impossible. We held dear the days we didn’t get any news: Saturday and Sunday. Suddenly weekends meant something new, and became a shelter. The paintings on the wall in the hospital waiting rooms became these incredible gifts, these escapes. Art suddenly meant something different in our lives, which felt under siege during that time. There seemed much more at stake, and, man, did I appreciate whatever vignette of hope an artist offered me during those times. I don’t know if that illustrates the recuperative potential of art for you, but for me, something as simple as this—essentially a painting on the battlefield—soothed me in that moment of anguish. My wife, Lori Waxman, is the art critic for the Chicago Tribune, and to this day, my favorite piece she wrote was about the artwork in that hospital.

I spent a lot of time with my parents during that year; they came to visit us quite a lot during Lori’s treatment. My father is a physician, and I appreciated so much more his contributions to the world as a healer. When I came back to the studio after spending a long time away, I began working on What Dust Will Rise for dOCUMENTA (13). I spoke with a friend of mine, a psychoanalyst, about how I felt I could never really work with our experience as a family with illness and healing in a direct way, but it was so present in everything I felt. My friend pointed out the sparse vitrines, the travel to Bamiyan and the voids and absences that I was making present, and the workshops reintroducing stone-carving to the Bamiyan valley—it was all in there. So yes, to answer your question, this desire to suture, to mend the breach, all without erasing the wound is embodied in What Dust Will Rise.

In May 2012, I collaborated with Afghan sculptor Abbas Allah Dad—who survived threats from the Taliban for his realistic work—and restorer Bert Praxenthaler on a workshop with local students in a monastery cave close to the niche where one of the Bamiyan Buddhas stood. Their aim was to recuperate the traditional skill of stone carving that has for centuries been part of the heritage of the Hazara region.

What Dust Will Rise? recreates selections from the State Library of Hesse-Kassel that were destroyed in a fire in the Fridericianum—which has served as one of the main venues for the Documenta exhibitions since 1955, and is where my project was sited—during a bombing by the British Royal Air Force on September 9, 1941. With the help of stone carvers from Afghanistan and Italy, I remade these lost volumes out of travertine quarried in the hills of Bamiyan, where two monumental sixth-century sandstone Buddhas were dynamited by the Taliban. The undertaking conjures tombstones and recalls the tradition of stone books serving as surrogates for the illiterate.

I do think it’s been there all along: paraSITE, RETURN, Enemy Kitchen. In fact Enemy Kitchen was when I began working with Iraq War veterans. Former combat veterans who became artists like Aaron Hughes have really articulated for me the recuperative potentials of art. In Aaron’s case, his amazing TEA Project (2009-ongoing), a performance where he prepares Iraqi tea—the very thing he had to refuse as a soldier when Iraqis offered it to him and his platoon, attempting to make them guests instead of invaders—has become a paradigm for so many war veterans who have turned to art, because, as some have put it, art succeeds where language fails in attempting to put back together fragments, and offers a space that is not mere apology but accountability. Aaron has worked with a vast, nationwide network of artists to put together a Veteran Artist Movement that seeks, among other things, to dismantle the militarism that seeps so deeply into our country’s DNA.