In Lucy's Words...

I studied as a sculptor, and while I focus primarily on making moving image works and installations, I think of how images are connected through time, and presented in space, as a fundamentally sculptural concern. I also make sculpture, photographs, and drawings.

My current body of work—a series of moving image installations and related works in other media—is titled “The Drumfire.” This series takes the genre Western as a point of departure to explore themes of material state change, pressure, force, and cycles of violence in the (de- and re-)formation of the Western United States. Each of these works is grounded in physical dynamics that literally, psychologically, and metaphorically have shaped the western landscape: the transformation of solid rock into concrete in Ready Mix; extreme air pressure caused by shock in Demolition of a Wall (Albums 1 and 2); and in this new film, water pressure, its build up and release.

I made Ready Mix at a concrete and gravel plant in Central Idaho. I was thinking a lot about the built infrastructure of the country, and of the West in particular. It was commissioned for the opening of Dia’s newly renovated building in Chelsea, and realizing the work for that space with Dia’s support also put the work into dialogue with the Land Art movement and those works’ complex relationship to histories of the Western imaginary and built forms.

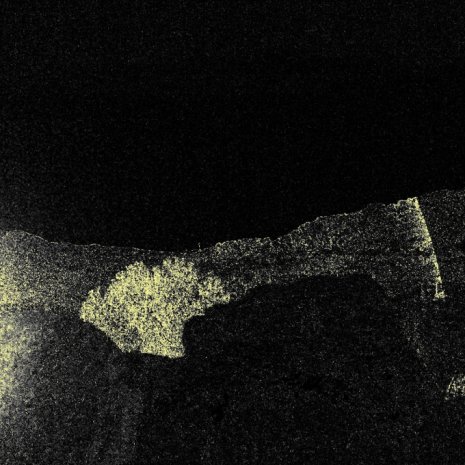

Working on an explosives range built atop the site of thousands of years of indigenous civilization, where structures from the last several hundred years could still be seen in ruins alongside the blast pads I was using, it became crucial to me to think through a way to image shock waves that would address their impact on land over time—without reinstating the familiar spectacle of a centralized explosion. An energetic event is required, however, to produce a shock wave, so I set up and detonated large explosive charges, but framed them out of the image.

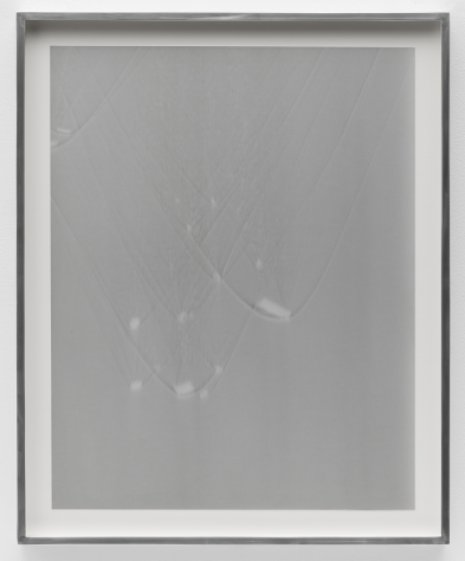

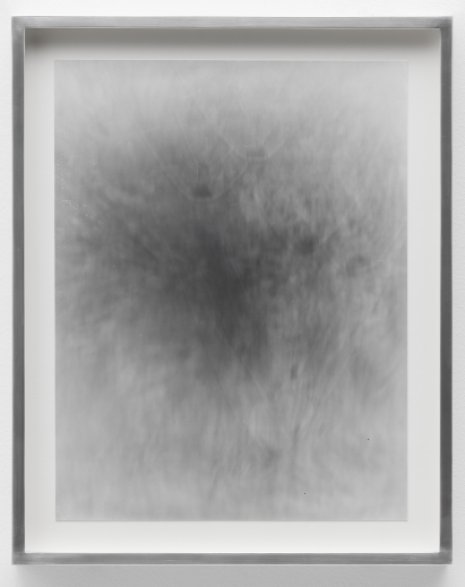

As I began these moving image works using extremely high speed cameras, I got interested in an almost inverse process, making still images called shadowgrams. These are camera-less images, made by exposing a photo-sensitive substrate to a microsecond flash of light while an object(s) passes in front of it at Mach speed.

My new work is set along the Klamath River in Southern Oregon/Northern California. Focused on the role of fluid dynamics in the shaping of the Western US, it concentrates on the removal of the largest and oldest dam on the Klamath, a curved concrete gravity dam called Copco 1, completed in 1918.

“The Drumfire” is in some ways a proposal for another kind of Western. The other genre that’s underpinned my thinking has been horror, which could also be an apt way of describing the way “the West was won.” More and more, I’ve come to see the conventional Western as telling the story of the invention of private property in what would become the United States, the violent removal of anybody already living on that newly designated land, the protection of that property by the police, and the imaging (cataloging, indexing, mapping, surveilling, exploring, exploiting, spectacularizing, selling) of that property through photography and moving images. Both still and moving image capture technologies developed in parallel alongside the expansion west of industry and settlers, and the two strands are inexorably intertwined.

I was never much interested in Westerns growing up. As far as mediated images of the desert I did relate to, I leaned toward another kind of cartoon: Krazy Kat and Looney Tunes. I can see now how beyond the dark humor I enjoyed even then, the violence embedded in each of their repetitive structures resonated with cycles of extreme violence that underlie the expansion and development of the Western United States—social, structural, infrastructural— that I didn’t yet understand. This is something the composer I collaborate with in all these works, Deantoni Parks, a percussionist originally from Atlanta, Georgia, and I, connected on deeply when we first met.

Parks, a percussionist by training who today plays with Andre 3000, John Cale, and under his own moniker Technoself, is a crucial collaborator, and the sound in each moving image work is paramount to the piece. Like all the works in the series, the new film will have a quadraphonic sound mix. This spatial audio layout is conceived as an alternative to the traditional 5.1 sound of most cinema, where the 5th channel is the speaking voice, installed behind the screen, and the other four channels are surround.

While many forms of sound design and music are developed and deployed in each work, drumming as a form that embodies both foreground and background, alternating strike and interval, is the pulse each work is based upon.