Chapter One

Communication takes many forms and velocities, doesn’t it? In these uncertain months encased, as they still are, in an era of lightning speed, I find myself thinking about letters sent by ship centuries ago, imagining the eagerly awaited carefully-penned responses arriving many months later. Amidst the disruption, social distancing, uneven impacts and severity of the global pandemic — and Firelei Báez right in the heart of New York – we asked art historian, curator, and professor C. Ondine Chavoya, a member of the 2020 Herb Alpert Award Visual Arts panel, if he might re-read Firelei Báez’ Herb Alpert Award application, and, with his knowledge of her work, offer up some questions he was curious about. In lieu of a rat-a-tat-tat back-and-forth email exchange, Firelei received his attentive enquiries en toto and was able to answer them with considered reflectiveness. Slow food for nourishing thought.

Firelei Báez:

As an undergrad I first read Octavia Butler’s sci fi novel Kindred, where a black woman is pulled from the present back to nineteenth century antebellum south whenever her young white ancestor was in peril. The phrase “beyond unalterable limitations” came to mind. Two things became clear to me since then: first, the power of a creative mind to bring clarity to—and make present—such a traumatic past, and second, the magnitude and bond needed to survive as a people despite and beyond such irreparable limitations.

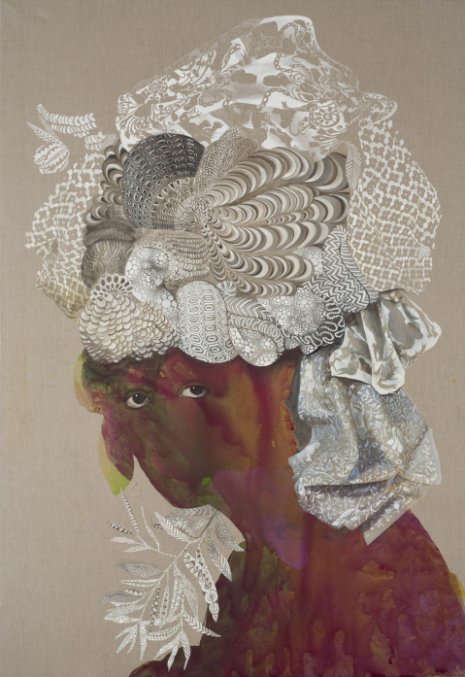

Beauty, as I understand it, is a mutable thing. Something that carries remnants of a previous definition but in its evolution shows us a bit of what we have been missing. In this sense my works are multivalent in that they seduce you with presumptions of the known, and conscript you as a co-conspirator in breaking down the very structures that tried to eradicate us in the past.

In a literal sense this has always been the case. It might be easier to understand this in terms of major shifts of scientific awareness: gravity, the curve of the earth, the multiverse, the relativity of time. These are things that need some distance, some self- awareness untethered from singular identity to be fully understood. The same applies in every small moment of how we navigate throughout the day: what we eat, who we consider family, how we get from point A to B, all have such broad interconnected effects on the world at large. Navigating the world from the margin is a gift of sight, of separation without division that gives better glimpses of the things beyond the singular self. As an artist I listen closely to the voices of elders before me, theorists, aunties, the untold histories nestled in by bedtime story tellers who constantly reiterate the notion of de-centered clarity.

****

Ideally, all my works would be sensate, felt through the body as much as through the mind. This is much easier done in large-scale sculptural installations. When invited to make each public artwork, I do extensive research on each site so that my work is responsive to it. These large-scale works are collaborative efforts that start as a sketch in the studio but usually require architectural plans as well as building and scenic crews to be realized. My studio works tend to be more introspective and poetic. In these I am free to connect geographies, histories and bodies more freely than in the public sculptural works.

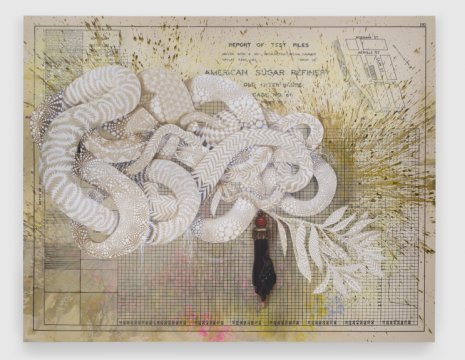

The Ciguapa Series began after I graduated from Cooper Union in 2004, at a point where I felt I had the freedom to return to figuration. I have always been struck by, and made more aware of as a little kid trying to learn English, the gendering of Romance languages, where the feminine is always conceptualized as passive i.e. silla/chair, luna/moon, montaña/mountain—a feminine ideal lover patiently waits to be activated. On the school bus in Miami I passed a city sign that had a quote by José Martí that said “las palmas son novias que esperan,” (the palms are waiting brides). As a teenager, this placid ideal seemed like the antithesis of the dynamic, self-sufficient women I was raised and surrounded by. The folktales I was told as a child all countered this ideal as well; specifically that of the ciguapa, a female trickster story from my birthplace Hispaniola, which was really generative to the conceptualizing of the Ciguapa Series. She is described as a feminine creature/archetype from nature/the wilderness. In her stories, she is a total badass, virtually untraceable because of her backwards legs, able to use her power for good or evil, to break generational karmic loads like those Junot Díaz suggests in The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao. The initial artworks started out as smaller test-card-like silhouettes that then became more elaborate, larger forms. Both were meant to act as open signifiers upon which viewers could project their own meaning. The figure can either be a fierce, elusive creature or a passive houseplant gathering dust in a corner. For me, they acted as visual/linguistic antonyms, to showcase the psychological and even metaphysical defenses people before me had built against linguistic and cultural invasions. These works were propositions, meant to create alternate pasts and potential futures, questioning history and culture in order to provide a space for reassessing the present in ways similar to Octavia Butler’s science fiction.