Chapter One

The following text was generated from an email exchange between Phil Soltanoff and Raelle Myrick Hodges, theater director, creative director, 651 Arts. Both living in New York, they initially planned to meet in person before getting started. Then, almost immediately, they found themselves thick in the geographic center of the Coronavirus pandemic 2020. You may notice disjunctions as well as flow in their conversation; please realize that life inevitably interrupted their conversation in a complex, choppy time.

I am sending LOTS of love to you and yours and hoping you are safe. Life is moving strangely; nevertheless, I am well - just taking care of a lot of people. Learning Lessons. Growing…

But, this is a respite - to be able to discuss art!

Stay safe,

Raelle

This COVID virus has actually hit my family (NOT my mom), but I have been managing family matters as the involuntary eldest.

It is crazy times. I am in the process of trying to change my phone number because it was published as a public porn site with my location...IT HAS BEEN AN INSANELY STRANGE WEEK.

Today is the first moment of stillness I’ve had since last Monday.

Let me send questions shortly.

Raelle

Here we are: Theater Folx in the middle of a pandemic. And with the loss of life, I am continuously struck by the need to make. Even when it can feel…too complicated…During the time of 9/11, there was a feeling in New York that may (or may not feel reminiscent) of our current predicament. How does one create/make/depict…with death being 'next door?’ Is there a time to be inspired/to create in times such as these?

Raelle

Hi Raelle,

More digressions about COVID...I was here in NYC when 9/11 happened -- a similar sense of being on high alert 24/7 and everything smelled like it was burning…now everything you go near or touch may be infected and could kill you. An elevator ride downstairs to get the mail means wearing a mask, don’t get in the elevator with another person, what is your plan for touching the buttons? I lean toward going overboard with the fear…Nearly every day my wife Katherine and I accidentally break a drinking glass. Too bad…nice tumblers from France we think as we sweep up the shards but who cares about finery in times like this…We’re binge-watching…Engrossed by Fred Astaire and Judy Garland in Easter Parade last night. Pure escapist entertainment, but much needed -- Fred Astaire’s clothes fit him perfectly. When he dances in tails it reminds me of how my cat Franny used to move—effortlessly and without a wasted gesture. But worrying about aesthetic questions seems inconsequential, callous, even shallow at a time like this. I spoke to a friend of mine during 9/11 (a well-known playwright and director.) The question about the importance of art in tragic/consequential times seemed obvious to him. “It’s what I do,” he said. I can’t say that yet…

Phil

(Later in our process we learned that director, actor, producer – and member of the 2020 Herb Alpert Award Theatre Panel - Diane Rodriguez passed away. The following are email fragments…)

Hi Irene and Raelle,

…about Diane. I’m still in shock about this. Diane and I worked together at CTG [Center Theater Group]. She was hugely supportive of the whole project I was doing. It was a brand new adventure for CTG and she spearheaded it. She was always kind to me…I volunteered to take a bus to the theater everyday…she got me a car. Thanks, Diane. I remember her arguing (forcefully) to produce the piece at the Kirk Douglas Theater. I never got a chance to tell her that the ideas I developed in LA – I’ve borrowed from and used in subsequent pieces. Miss you, Diane – You were a force for new work.

Phil

You have to understand: Diane was a true mentor for me and my brain is ACTUALLY broken…still crying can’t really think straight right now. Speechless.

Raelle

What follows is edited from Raelle and Phil’s email conversation about Phil’s work, which took place between March 15, 2020 – April 10, 2020.

Sound. It helps me see. In fact, I organize performance structure musically. I collect sounds. I have acres of field recordings that I’ve made over the years. I’ve taken fragments of these recordings and manipulated them through various audio software until they become something else. Some of the resulting sounds have become like little friends of mine—they trigger certain meanings for me. I use some of these sounds in every show I create. In fact, for More or Less, Infinity, I took a recording of a fax machine, mangled it with audio software, and built a library of sound from the results. I then composed most of the sound design for the performance from those results.

The babble of the brook…the twinkle of the star…the loud guy in the next apartment. No seriously, I’m always in some kind of receptive, observer mode. I do a lot of looking and listening. The times I try to force an idea to happen, I fail miserably. I observe. I have faith that ideas will come to me if I just look. For instance, to whom it may concern came from looking out my 33rd story window in Hell’s Kitchen. Traffic, when seen from high up, takes on a different reality than at street level. Looking at traffic from above, mixed with the film KOYANASQAATSII (which speeds up the action of traffic flow) mixed with John Cage – all led me to ideas for a performance. I was looking at stuff, connections occurred, ideas came up. Another example of looking leading to inspiration: every time I get in the elevator to ride up or down in my building, I try to find the pattern of the ride. I’m obsessed with finding patterns. Who’s getting into the elevator with me, the buttons they push, positions they stand in, what they look like, whether they converse or not. I’m observing and something is revealing itself. The process of inspiration is overrated. I just want to be open to the next experience of my life. And I file those experiences away.

Regarding $$. I am going to make art whether I’m funded or not. Funding makes life easier for sure -- but I’ve constructed a whole aesthetic from having nothing to work with…

I meet too many people who have their minds made up before they experience a piece of theater. I hear something like, “I don’t like that sort of work!” I think mainstream narrative-driven work can learn a lot from performance-driven work and vice versa. A cross-pollination can and is happening. For instance, would the musical Tommy really have been possible without the innovations of Robert Wilson? I don’t think so. And what can performance-driven work learn about catharsis from the mainstream? Ivo von Hove seems to be having great success these days. A Broadway audience seems to accept his visual and aural interventions. Where do we go from here?

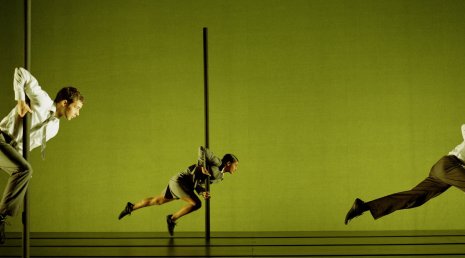

to whom it may concern (created in 1996) started with a public space and ideas from John Cage. I built the piece in a courtyard then re-mounted it using the entire floor of a NYC building. No psychological realism, no characters talking while they moved around couches. I explored constructing narrative from walking patterns, loops, repetitions with actors in business suits. The performers jumped together, changed direction, moved in unison, set out on their own, came together as a group, moved in slow motion. I organized the movement patterns into loops: first a group of 3 walked, then 4, then faster, then a larger group. I gave the audience something to hang on to by the way I built the patterns: repetitions, juxtapositions, different rhythms organized around the musicality of movement in the space.

In retrospect, I was beginning a new way of working based on noticing and creating ‘facts’ in the performance space. ‘Facts’ are objects, happenings, elements (for example, sounds, costumes) that are simply present. (For those interested in reading more about my ideas about what constitutes theater ‘facts’ please see the question about ‘facts’ later in this interview.) With to whom it may concern, I implemented two rules that inspired our way of working: events had to be ‘Fact-Driven’ (events which are purely physical occurring in the here and now) and events had to be compelling to watch.

I knew I wanted to create without a play. This didn’t mean I wanted to exclude text completely. I just wanted text to be an element in the mix, not the main deal. I tossed SILENCE onto the table. Cage’s ideas were seismic for me. In 1996 the opportunity was right to use a space, not a theater; the building was a 55000 sq. ft empty office. The space itself was electric. Thrilling. Then to build a performance of some sort in it - that idea felt alive. The space was perfectly wrong for theater but that wrongness created the perfectly right juxtaposition for the performance.

Using Viewpoints (which by 1996 I’d been working with for four years) I forged an ensemble of 12 men and woman, and I costumed them all in business suits. Why? I use suits all the time. I’m fascinated by business suits because most everyone has some kind of reaction to them. Suits are everywhere. They’re a presence in and of our world. They can make us angry, and uncomfortable. The uniform of power/big business screwing up the world. Someone else might get jealous of anyone wearing a suit as if the suits were yelling, “I have it all together and you don’t!” The point is, the costume provokes a complex response propelling the imagination of the viewer. In a way suits take the place of traditional character development. Instead of psychology, I have a ‘fact’ called a suit.

Crashing performers in suits with a setting or activity not meant for suits; I did this both in to whom it may concern and later in many pieces. Plan B, for instance, is performed by four ordinary guys doing acrobatics dressed in rumpled business suits. We have all seen circus acts. Performers in sequined outfits, flashy and the like, doing somersaults. But what if they perform those somersaults in suit and tie? The costumes work in juxtaposition to the circus acts. They wake each other up. This approach really began with to whom it may concern. Juxtaposition becomes another way, a different way to rehearse, tell a story, and to present ‘facts’ in a space.

Something else that I embraced in to whom it may concern is that we live in a technological world. I was able to explore this with very little equipment -- just six boom boxes and a sound system. Totally cheap old school stuff. Work that recognizes the technological world we inhabit interests me. I’m not for a minute suggesting that a piece of theater needs to have television sets and cell phones in order to be hip. In fact, too many productions add technological touches to signal to an audience the production has a contemporary mindset. Set dressing and props do not qualify as innovation or consciousness. I’m interested in a kind of theater where an awareness of the digital world is present even if contemporary technology doesn’t actually show up in the performance. Or very little technology. For example, the work of Jerome Bel. The technology is often dirt simple. His piece Cedric Andrieux uses only a wireless mic. But the performance uses the mic in a way that signals Bel understands the world outside the performance.

What was vanguard yesterday almost always becomes more accessible today. Take Monet for example. When his paintings were first exhibited they caused an uproar. Now, not only do the canvases sell for millions but copies of Water Lilies can be found in every campus bookstore and hotel lobby across America. Theater conventions wear out their welcome too. What was exciting is so over-used that theater becomes boring and ineffective. On the other hand, something once popular and innovative can be discarded and left in the dust of the past. Then, suddenly, the convention resurfaces and is rediscovered. What’s old becomes new again.

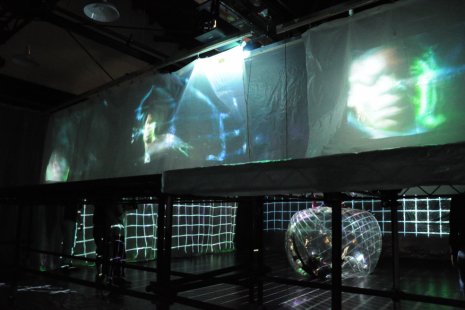

Conventions constantly need to be revisited and reinvented. I like to play around with objects, processes or places and engage in a practice of looking at something familiar and then working with it so it becomes unfamiliar. Take big blue water cooler bottles for instance. We see them everyday parked in offices. We ignore them, don’t give them a second thought. But what if I take a bunch of these bottles and put them somewhere else? Somewhere where they don’t belong, like in a line outdoors. Or use them to produce sound. The water bottles become something new and strange. They become ‘seen’ again. At the Center Theater Group in L.A., collaborating with Jim Findlay, we started our process by investigating a material: plastic. I chose it because we’re all familiar with the material. Our relationship to plastic is almost always toxic, dismissive and negative. Can I flip that? Can I take various plastic materials and discover (via rehearsal experimentation) other qualities plastic possesses? Can we find something beautiful or poetic in plastic? Can we make our relationship to plastic more complex?

How do I define ‘aesthetics in theater?’ That’s a giant question. Allow me to riff and stumble a bit. I’ll also respond to your second topic about starting out as a more traditional director working with plays/texts and realism etc…

We all have lots of reasons to go see theater. Got a date on Saturday night and want to see something spectacular or want to go engage some challenging ideas, or Friday night and in the mood for something nostalgic. I have one major reason to go to the theater: to experience something I don’t know. Romeo Castellucci’s work does this to me sometimes. In Inferno he walked onstage, introduced himself, changed into a bulky suit and then was attacked by a half-dozen or so police dogs for 10-minutes. What??? A wake-up call, a creatively confusing situation. Shocking in this instance, but shocking isn’t always required to turn my world upside down. Robert Wilson also blew my mind. I saw Einstein on the Beach in 1992. The program announced: take an intermission break whenever you like. But I never left, and the opera is an epic five hours long. Halfway through, a large rectangular box, brightly lit, slowly made an ascent from floor to ceiling. The event took about half an hour. I started to leave. Then I watched for another minute. Again I started to leave. Finally I just stayed put for the whole glacially slow event. I never left. WHY? Fascination. Flux. Repetition. Deep minimalism. WOW. Amazing.

In the early ‘90’s my head started to explode with exciting ideas and confusion. I’m completely embarrassed to share this, but during that time I went through a great deal of doubt and torment about how to direct theater and think about art. How could I integrate everything I already knew about theater with the innovative forms I was experiencing? The fact of the matter is I come from a traditional model of theater making. Plays gripped my imagination putting me in a very stuck and reverent place. I felt responsible to dig out a play’s essence, like a piece of sculpture buried in a block of stone. I directed tons of traditional plays with this mindset. But my aesthetic was being turned upside down by thrilling new work: performance-driven work like Reza Abdoh, Meredith Monk, The Wooster Group, Richard Foreman, Hanne Tierney, Robert Wilson, Pina Bausch, etc. The power, innovation, visceral sensuality of the theatrical experiences I was witnessing inspired me to forge some kind of new path.

I started asking questions about all kinds of theater related things -- like performance space, about character, about event, about duration, about scale, and on. Take scale, for instance, meaning both the size of the performance and the physical structure the performance lives in. Who says theater needs to be squeezed into a traditional proscenium or black box? What happens when you put an event in an airplane hangar or an old dilapidated hotel or an elevator? Utilizing an innovative venue wakes up an audience. Entering the space feels like visiting an amusement park. Or what happens if you reconfigure the event for both the performers and audience? What if the scenes you’re watching happen down the hall, in the bathroom or in a stairwell? How about if those scenes repeat? What if many events are happening all at once? And what if the audience can move around the space and CHOOSE which event they’d like to watch? And for how long? Like visiting a museum -- the entire dynamic between performance and audience shifts. These ideas might seem like old hats now, but concepts using alternative spaces and scale were fresh then.

In 1992, around the same time I saw Einstein on the Beach, I met Anne Bogart and she totally rocked my world. While teaching at Skidmore, I took a weekend-long workshop with Anne and completely got her ideas about space and time in the theater. Instead of starting from the inside/out - or some American derivation of the Stanislavsky system - working with Anne focused my attention on the outside/in. For instance, how to consider and work with the physical distance between performers: what happens when the performers move close together or further apart? And speed, how fast or slow are the actors moving? I was starting to become aware of theater as a painterly surface, a choreographic playground. I had been struggling for years at Skidmore to find a way to describe and work with physicality for the actor that wasn’t dancer-y. Anne has names for these perspectives: spatial relationship and tempo. I understood them intuitively but after working with Anne I had a vocabulary to work with. I was moving away from traditional theater to a different understanding of theater space and time, towards a more abstract theater built on the Viewpoints of spatial relationship, repetition, tempo, shape, kinesthetic awareness and architecture. (Viewpoints was invented by choreographer Mary Overlie, expanded by Anne Bogart and, since the 1980’s, Viewpoints have been central to Anne’s approach to creating new work.) All these ideas derived from post-modern dance terrified me, turning everything I knew upside down. My truth machine was saying YES but my classic theater training was screaming NO! Wait a minute! I didn’t listen. I did something great: I walked towards these ideas, towards what I was afraid of. I walked towards Viewpoints and started working with them immediately. They became my main vocabulary as a director.

I also walked towards the plays of Charles Mee Jr. Mee’s work was scrambling everything I’d been certain about: character development, psychology, linear event, cause and effect, etc. His plays were challenging all of this. A character might launch into a full-page monologue of a mathematical equation, or another might burst into a pop song. And the playwright literally offered me free reign to cut, rearrange or insert any text I liked or didn’t like. Mee defies conventional theater form. Encountering his work was my first deep dive into episodic structure. Could I create a staging using only Viewpoints? Could character be created with physical gesture instead of psychological investigation? I willingly jumped into more abstract, postmodern waters and just started swimming.