Chapter Two

We were, and still are, living through a moment of extreme violence against women in Puerto Rico at the time when Venimos desde el futuro came together. There were a lot of immediate protests in response to specific violent attacks—but in those moments of crisis, sometimes the political discourse is reduced to the level of “please don’t kill us” or “don’t rape us.” Sometimes it can’t be helped, it is that dire. But for us at that moment, despite the fact that we had to address violence directly, it seemed important to also insist on thinking in transformative, perhaps utopian terms.

At Beta-Local we were spending a lot of time thinking about pedagogy and how to get around received and tired pedagogical forms. So though we wanted to think in utopian terms, we did not want to sit around a table and make a seminar on “feminist utopian caribbean thought.” Instead, we wanted to be it, to do it. This is how Venimos desde el futuro came together. The idea was to create a radio station transmitting from 100 years in the future, after the end of patriarchy. It was organized rhizomatically: I was in charge of one day’s programming, and other people were in charge of others who asked others yet so that by the time we were actually transmitting there were about 40-60 people involved and no one really overseeing anything, I didn’t know at least half of the people! Everyone—writers, artists, activists, lawyers—was generating new material or curating works for the transmission. It was chaotic and beautiful. The last transmission was an hallucinatory 4 hour live improvised session which began with Ezequiel Rodríguez interviewing singer/persona Macha Colón who described how she was happily living a life as a dolphin and could only regain her speaking voice with cheap cola-champagne. I am not sure what people even made of it, those who did listen in. But for me it was important to see people show up for that kind of communal invention, in the midst of a crisis. For me, all of this work is pedagogy (collective radio production, people self-organizing), which is separate from my work as an individual artist and, for the most part, my artwork. It is important to mark the difference because I am interested in processes and setting things in motion, and also because these projects involved many people at once.

Maybe about 7 or 8 years ago I was reading, I am not sure which French writer, on the general subject of experiencing a place and I realized I was trying to adapt very specific thinking—related to 20th century Paris—a particular economy, way of moving, sounds—to the place I was in—2010 Caribbean semi-rural spaces. It wasn’t absolutely useless, but it was more as if I were using the wrong tool: it takes a lot longer; you miss some things, and you may be ruining the mechanism. I think we—I don’t think this is particular to me, but to a lot of my peers—feel like there is a process of recognition, of being with a place, listening to it, and thinking about the way all of us interact sensorially within it; that needs to happen before we theorize, and before we create abstractions and name things. The walking seminars are a way of doing this move together in a very slow, high-resolution way.

We walked sometimes with dogs, sometimes with horses, and there is always a moment when the dog or the horse cannot keep going. Humans are pretty versatile in terms of terrain. Forget about cars. Walking just switches a lot of things off—your sense of time changes, your perception of the weather etc. Then there is the feeling of getting lost which makes you pay attention to absolutely everything. I think there are two ways that I managed to put myself in a position for something surprising and unexpected to happen, to learn something I had not even known was out there to learn. One is you stay someplace for a very long time. The other is you walk without knowing exactly where you are going. In both cases you will eventually you will run into something unpredictable.

Walking can also be a form of auto-pedagogy. Not really teaching others, but teaching myself. There is an educational philosophy/practice called Reggio Emilia that was developed for elementary school children during post-war Italy. I won’t go into it at length, but an important concept in relation to it is that the place is the “third teacher.” I spent some time thinking about this when my children were small and I think, in this case, place is the first teacher, and I am in charge of logistics.

Yes, I think so too. It might be easier to speak about it through an example. In the case of the anti-colonial movement in Puerto Rico, there are two issues. One is that the only archive is the material archive gathered by the FBI and the police. In this case, ideology is embedded in the kind of materials and its interpretation, and I do not think there is any research against the grain that would make it otherwise. By contrast, there is no record of loves, debates, or dissent. Some of that is by choice because it was a clandestine movement.

The question then becomes how can we build on, play, or invent if this subjectivity, its form, its complexity is always suppressed and erased? As the monoculture spreads, there are many many subjectivities that are erased, and no amount of uncovering will bring them back. Whole languages, whole ways of thinking about the world are systematically erased. In Puerto Rico when a whole generation of anti-colonial movement is persecuted, put in prison, etc…people really do disappear, those ideas are suppressed. You can memorialize, but it is hard to question, expand, or mess with because it is considered either heroic or criminal. My position is that the archive is not useful (with rare exceptions) to people whose ways of thinking about the world have been systematically erased. Instead, what we have open to us in fantasy, wild recombination, new languages, experimentation in order to give new meaning to the world.

In Nicaragua the Sandinistas built schools for deaf kids in Bluefields, but in fact this community had already begun to create their own language and resisted learning Spanish Sign Language, inventing a language that has been developing since the 1980s. Some language researchers that have been studying it for 3-4 decades now have found that complexity in the language is added by each younger generation, they play, the stretch, they add, they make errors—the malleability is in this lack of respect, and pushing forth formally, sense will follow later. In order to grow complexity they need to inherit some work from a previous generation but they also have to imagine and play with it as well.

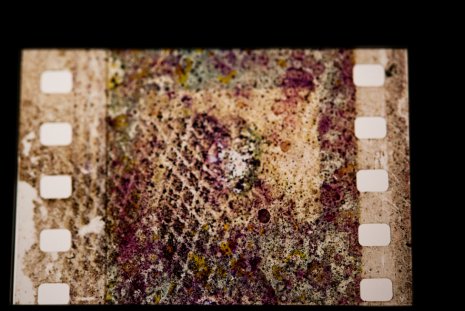

So, where I am going with this is that we need to create new materials. Aside from political thought, language (though language is a material thing too) or theoretical approaches, we also need to think with the sensorium. We need to populate the world with new images and objects, creating with the maximum amount of stretch and invention that sense will allow, so we can then go a bit beyond that into nonsense as well. We need to break with some things too, such as reliance on “story,” “progression,” and “representation.” Those are just a few forms, but they are not everything. I think what I am interested in is pushing sense and nonsense, expanding language, speaking from group subjectivities that are largely absent from material culture. I have tried to put this in practice through formal experimentation but also paying close attention to forms of being, produced within other parts of life. In Otros Usos (2014) I shoot through mirrored objects. The idea of transforming the scale through the mirrors, came from watching fishermen who were returning to fish in what was once a restricted military dock. They chose to ignore the scale, and instead use it as a shore, so simply using the remains of the base in a counterintuitive way, letting the scale of the dock just be waste.

I think there are images without spectators, and there are experiences without spectators—that is, art forms in which “audiences” are unimportant, irrelevant. In which “communication” is beside the point. I am interested in exploring those possibilities in film. I am not sure if I have done much of it yet, but I am headed that way in some projects. However, I think there are no signs without spectators, or rather that spectators, audiences, publics, perhaps because of the expected passivity as a receiver, in specific forms of art, are implicitly “readers of signs.” So I think that when I show work in a museum or a film festival, there is no way around the audience’s system of signs. After realizing this, my first thought afterwards is, of course there must be a way!

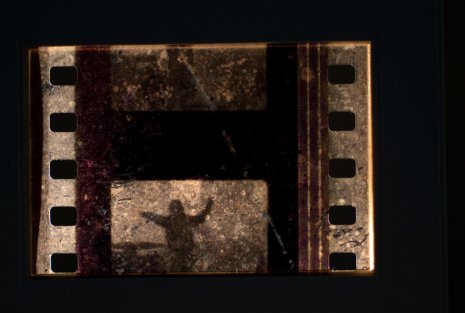

For example, I have seen countless films and read countless essays on the anti-colonialism movement that imagine a reader or an audience who might know some things, not others. But when does the work of thinking sensorially, materially about this history, these forms of thought begin if we are always explaining the basics? For example, in the case of Safehouse (2018) I wanted to make work for us, for those of us (whoever this might be) who identify deeply with the idea of liberation and who want to think from this position in order to question, expand, make more complex, and even resolve traumas and create a new language.

This is not something that only Puerto Ricans will understand, any person or group who has been involved with a collective political project that requires action, common purpose, discussion and serious consideration of violence, the violence of colonialism and violence in response, knows what Safehouse is trying to do. This does not mean that people who do not know are unable to listen in. Of course this happens as well. Just as women have played male-gaze-spectators in mainstream cinema. Audiences can shift their positions, as the film enacts an imagined audience. For example, in the case of Safehouse, the imagined spectator is someone to whom the idea of the collective work of liberation is not a past historical event but a present task. If a work implies a specific subjectivity as its ideal spectator then each viewer of the work has to adjust to that position to understand it.

###############

Almudena Escobar López is Time-Based Media Curatorial Assistant at the Memorial Art Gallery in Rochester, and a Ph.D. candidate in Visual and Cultural Studies at the University of Rochester. Her research questions the limits of institutional archives through alternative collaborative approaches to knowledge. She has curated screenings and exhibitions at film festivals, cinemas, and museums internationally. In winter 2018, she co-programmed the Flaherty NYC series ‘Common Visions’ with Herb Shellenberger at Anthology Film Archives. Her writing has been featured in Vdrome, Vertical Features, MUBI Notebook, The Brooklyn Rail, Afterimage, Film Quarterly, Little White Lies, and Desistfilm Magazine . She currently serves on the Board of Trustees of the Visual Studies Workshop (Rochester), and the editorial board of InVisible Culture: An Electronic Journal of Visual Culture.