Time and Space

SLA is a piece that I did when I was at UCLA studying with Mary Kelly. I was rather aimlessly trolling the library and came across a book containing all the communiqués that the SLA had sent to the public during their somewhat brief existence. Included in that collection, of course, were transcripts of the four audiotapes that Patty Hearst and the SLA made for her parents during her kidnapping in 1974. I was fascinated by the texts because they were addressed to her parents but were also a communication to the FBI, the media, the public, etc. And, of course, she was speaking but she was also a filter through which the SLA was sending its message. So I decided to begin working with one of the transcripts. I started with the second communication, because it was the one in which Patty Hearst was the most suspended, somehow, between the world of her parents and this world of revolutionary politics. I was asked to participate in a performance evening and decided use the event to push my questions forward. I partially memorized the text, gave an audience the transcript of the text, and told them I was going to attempt to speak the text. I asked them to correct me when I was wrong and said sometimes they might have to feed me a line.

I sat on a stool looking into a video camera that I had set up between the audience and me and recorded the speaking. Of course I couldn't say the text accurately and people had to intervene quite a lot to correct me and move me along. I am not ‘playing’ the character of Patty Hearst; I am just trying to speak the text that she spoke. Similarly, the audience is not playing the part of the SLA, but their task does structurally cast them in the position of co-author. It was an experiment. Immediately I felt liberated from some of the confining conditions of performance. There was something really interesting about using performance to ‘make a tape.’

Yes, and their task - the fact that they had a task and a rather active one - distracted all of us...me and them from the self-conscious awareness that this was a performance.

What is interesting about the off-screen audience is what happens to the second audience that picks up a tape or sees the video. The existence of the off-screen audience generates an important awareness in the second encounter.The video audience knows that they could be but aren't that off-screen audience. The off-screen audience creates an imagined position for the audience or viewer of the video, a place where a viewer or set of viewers could be but, instead - because they are not in that position - they have the chance to reflect upon it. In doing so, they are able to reflect upon agency, political language and their own participation in operations of collective memory.

My experience working with Mary Kelly taught me a lot about the deep relationship between content and form. I believe that the form of a work articulates its content and vice versa.

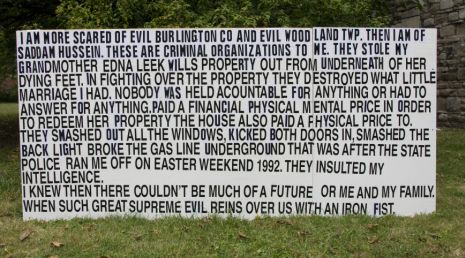

I try to be very precise with the aesthetic decisions I make in each work, even to say that I try to be precise about where and when I make aesthetic decisions and where and when I don’t make them but rather transmit aesthetic decisions that have already been made by someone else. With Yard (Sign) for instance, the installation of 147 or so yard signs. Some of the signs in the work are found but many are re-fabricated from found images. In this case, of course, the choices vis-à-vis re-fabrication must adhere as closely as possible to aesthetics of the original sign because why would I compose or express any aesthetic authorship in that sign space? Any choice I might make as to the color of the text, the size of the text, the handwriting, etc. would be completely arbitrary. The aesthetic choices I make in that work are solely ones related to the whole collection of signs: choosing certain signs for inclusion, constructing how the signs addresses people in space, what the whole means as a collection of particular signs and how to support the work’s aim to interrogate the speech, political and otherwise, that people make through and from their property.

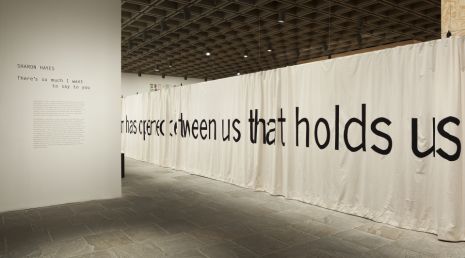

While I would say that I make specific aesthetic decisions with each work, one of the concerns that crosses over all the work I make is the way in which a work addresses its viewer, audience or public. My attention is acutely focused on the position of a viewer(s) and on using elements of form: scale, volume, surface, space, time to construct a precise address that allows a viewer to place and hold themselves in the field of concerns raised by the work.

I don’t find the word nostalgia helpful in understanding the complexity with which past political movements, events or claims circulate within the present moment. For me the present moment is one that is always pointing backwards and forwards. It is not one moment but a collapse of multiple moments. I mean this specifically, not generically. I don’t think everything exists in everything. At any given moment of time there are precise political debates or singular ethical propositions that originated in a prior time that, perhaps because they are unresolved, are brought forward in specific ways.

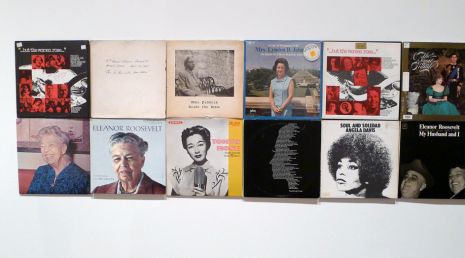

Gay liberation is one of these unfulfilled propositions. The GLF (Gay Liberation Front) formed in 1969 and was disbanded in 1972. Their political positions were largely eclipsed by a shift in gay politics from liberation to equality. But in 2007 when I was first asked by the MIX Experimental Film Festival in New York City to put ‘sound’ to 33min of raw footage shot by the Women’s Liberation Cinema in 1971, I felt there was an important, even a rather urgent, reason to unspool back to that moment to consider this gay political position that actively aligned itself with anti-racist, anti-capitalist revolutionary struggles and that decried the violence of conventional familial relationships, and of forms and institutions that upheld a rigid division of gender. I approached Kate Millett to respond to the footage because I was interested in foregrounding the process through which a re-examination of that moment might happen and to offer, again, both of us as witnesses.

I was asked recently what I mean when I say I stage ‘speech acts.’

The idea of words as action originates, as you know, as a proposition made by British linguist J.L. Austin in the term ‘performative.’ Austin articulates performative utterances as those linguistic constructions that do rather than say. His classic examples are the “I do” of a marriage ceremony or “I christen thee the Queen Elizabeth” in the instance of the christening of an ocean liner.

I do not enact performative utterances that are faithful to Austin’s identifications but, from his work and from that of theorists like Judith Butler who have examined the performative in relation to gender, I’ve been moved to interrogate the speech beyond our assumptions of its communicative value.

By this I mean things that are complex and things that are very simple. Obviously when more than a thousand African American men took to the streets of Memphis in 1968 wearing signs that say I AM A MAN, there is more going on than just communication. Certainly when I hold a sign with the same words at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in 2007 (as part of a work called In the Near Future), I’m not communicating in the conventional way we think of communication, where a speaker or set of speakers attempt to transmit a statement, question or message to a listener or set of listeners.

I’ve also been interested in more complex ways that speech functions as action as when I stood on the street at Sixth Avenue and 51st Street and spoke a ‘love address’ to an unnamed lover. I was moved to write a text to the most intimate of addressee, a lover, because I wanted to talk about war publicly at a moment when the space for such public discussion had closed down. As I stood on the street for those five days in September I was literally speaking to people passing by, I was looking at them in the eyes. I was trying to “communicate” with them but they knew and I knew that they weren’t the ‘you’ that the text addresses and, in that way, the text did not communicate with them. However, I would contend the text did act upon them in some form or another, with greater and lesser depth, meaning and significance depending upon their own choice to listen for whatever given period of time.

My interest in speech as action doesn’t depend on any idea of effectiveness. Most of my work is not effective actually. I would say it circulates along different measures of value. A friend once told me he wanted his work to either make someone laugh or make someone cry. Those two responses were a measure of success for him. I’m not interested in making people do anything specific. I make work to put something out into the world – an idea, a way of looking at something familiar through a different lens – that someone can use in some way as in the way you might use a book. You absorb it, you reflect upon it, you are moved or annoyed by it, it could change your life or it might open up some small space of action, consideration or investigation. It’s dialogic.

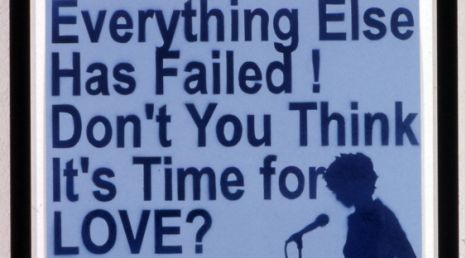

The form of the letter allows me to address a public indirectly and, as a result of that ever-so-slight-distance, people listen when they might otherwise not. I think they allow that, while they are not the ‘you’ I am talking to, they could or might be. I remember during the Wednesday love address of Everything Else Has Failed..., I looked into a small crowd of people who had gathered to listen and noticed that a woman was crying. This disturbed me for quite a while. Did the performance cause her to cry? Was there something in the text that reminded her of a painful situation of her own? Did she love someone from whom she was separated? A soldier, a journalist, a person living in an area of war? What is my responsibility for provoking her emotions? I stewed over this and then let go as, I think, the work asks me to do. The language or discourse of love is unwieldy; it is intensely generic, general, accessible but attempts to describe and name the most intimate and particular experiences or emotions. In that sense, I am less in control of the impact of this work than in any other I’ve made which has been a fascinating realization.

I remember Lorraine O’Grady saying in a public conversation that she stopped using herself in her work because as she grew older age and aging necessarily came into the reading of the work and she had no interest in that content. (I am completely paraphrasing.) I haven’t shifted away from using myself in my work and would perform again in future work if the necessities of the project demanded it. The decisions I make about whether to use myself in a piece (as in In the Near Future), or to cast an actor (as in Parole), or to recruit participants - in the sense that a group of people forms through some form of self-selection - (as in Revolutionary Love) has everything to do with how the body or bodies in the work contribute to the meaning of the work. In ITNF, I had to use myself for two reasons: one, that the actions of holding each sign in public, while an invited audience documented the event, were a form of research, and I had to be the body in the speech act in order to figure out how the speech act of protest makes meaning. To cast a body that would hold the sign brought up too many unrelated questions: How old should the body be? What gender? What ethnicity? Let me be clear, my age, gender and ethnicity have a great impact on the way in which the piece functions but to cast another body that would hold the sign would fix this relationship in a way that my use of my own singularity does not.