Chapter Two

“I've heard people talk about issues of representation and the content of culture. But I'm trying to figure out how to make Black films that have the power to allow the enunciative desires of people of African descent to manifest themselves. What kinds of things do we do? How can we interrogate the medium to find a way Black movement in itself could carry, for example, the weight of sheer tonality in Black song? And I'm not talking about the lyrics that Aretha Franklin sang. I'm talking about how she sang them. How do we make Black music or Black images vibrate in accordance with certain frequential values that exist in Black music? How can we analyze the tone, not the sequence of notes that Coltrane hit, but the tone itself and synchronize Black visual movement with that? I mean, is this just a theoretical possibility, or is this actually something we can do?”

—from 69 by Arthur Jafa, 1992

“I realized that the black voice was at the core (technically, formally, and spiritually) of why black music was powerful. People typically talked about cinema in terms of stories, narratives, thematics—but it quickly became clear that we needed (additionally) different concepts. So, for example, the idea of black visual intonation was conceived as the cinematic equivalent of the black voice. You’d never confuse Billie Holiday with Fela or Fela with Bob Marley or Marley with Charlie Parker or Miles Davis, right? Each has a certain signature relationship to the black voice (as transgenerational continuity) and with black vocal intonation specifically, whether in the voice of the performer or played out instrumentally, as a primary mode of expressive articulation.

What is the relationship between black music and Western music? African-American music is Western music—a lot of people don’t seem to realize this. I like to say like we are illegitimate progeny of the West (ill suns), in the sense that a lot of ideas were imposed on us (nonconsensually, so to speak), ideas which we internalized and made something new of, something unique and distinctively American, all without us ever being seen or accepted as the legitimate heirs of these ideas. Black people came to the Americas with the very deepest reservoir of cultural traditions, modes of expressivity.”

—from Love is the Message, The Plan is Death, Arthur Jafa and Tina Campt, e-flux journal #81, April 2017

“Nam June Paik, the godfather of video art, said that ‘the culture that's going to survive in the future is the culture you can carry around in your head’, and I always felt like the Middle Passage was a profound example of that. If you look at African American culture, the places in which we're super strong and have a lot of confidence are those areas in which our cultural traditions could be carried in our bodies. The incredibly rich traditions of architecture, painting and sculpture tended to erode in the Middle Passage, and, by extension, in our experiences after the Middle Passage. However, the places where we're strong – oratorical media, music, dance – those are the things that we carry in our nervous system. Those are the spaces where our expressive traditions and our cultural artifacts are bound up with the experiences that we've had here in the Americas, the cultural context that we came from originally in Africa, and in some ways where we imagine ourselves to be going.”

—from “Arthur Jafa in conversation with Hans Ulrich Obrist”, 2016, Serpentine Galleries

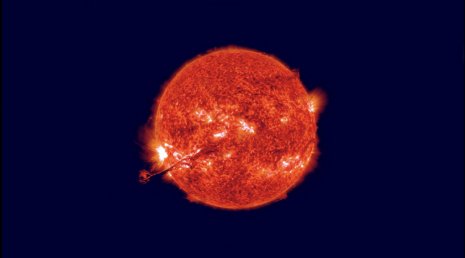

“One of the many things Fred Moten said that had an impact on me is that we normally think of jazz as a tension between a group and an individual: when the individual begins a solo, the group fades into the background. He argued that a better way to understand the individual is as an emanation of the group. Whenever there’s a sun in my work, I’m thinking about that: you see the sun blazing; then, all of a sudden, a flare reaches out and you recognize it as a single entity. Afterwards, it’s just absorbed back into the body of the sun; it’s an emanation. In hip-hop, nobody’s individual genius is in opposition to the group dynamic – otherwise it wouldn’t work. How many tracks can you find now with just one MC? They’ve disappeared like the dodo. That tension between the ego and the group is what’s productive because we cannot totally sacrifice our egos in order to work together: we need them to survive in this antagonistic environment.”

—from “As Brilliant as the Sun”, interview with Jayce Clayton, Frieze Magazine, February 22, 2018

“For me, so much of black being is bound up with a conundrum, dilemma, on an ontological level, we talk about it, argue about it often times…. For me personally, I think black being is intrinsically bound up with horror. I don’t think you can get around it. It can't be reconciled, or theorized away. One has to accept it, to live with it. And there is something about living in this irreconcilable space, something so fundamentally Black ...I remember reading somebody’s definition of the blues that says something like, Blues is not tragedy in the classical sense, blues is a tragedy that you’re complicit in, that you can’t extricate yourself from. Don’t even want to extricate yourself from.”

—from “Arthur Jafa and Helen Molesworth in Conversation” MoCA, April 2017

“Even in its title, then, Love Is the Message, the Message Is Death, is bound up with these complicated ideas around what it means to be alive and to not be alive at the same time, as a way of continuing to be alive, and what kind of cycle is produced by that. I was seeing this really amazing footage that's coming up more and more now on YouTube as Black people start to document abuse. With phone cameras you increasingly start to see the insanity of it being documented. I could make a five-hour long version of the film if I wanted to. For me, Love is the Message is about trying to re-sensitize people to the footage that we're seeing all the time. On the other hand, it’s also addressing Black people directly. It’s saying, ‘Yo, keep moving forward; they knocked us down, we turn that shit into an art form. They hit us in the side of the head, we turn that shit into an art form.’ We can't stop ourselves from being injured, but we can in a sense deflect the sort of insult that's added to the injury.”

—from “Arthur Jafa in conversation with Hans Ulrich Obrist,” 2016, Serpentine Galleries

*******

Pablo de Ocampo lives in Vancouver where he is Exhibitions Curator at Western Front, one of Canada’s leading artist-run centers for contemporary art and new music. He has curated screenings, exhibitions, and performances at galleries, cinemas, and festivals internationally. From 2006 to 2014, de Ocampo was artistic director of the Images Festival in Toronto, and in 2013, served as the programmer of the 59th Robert Flaherty Film Seminar, History is What’s Happening. He was a founding member of the collective screening series the Cinema Project in Portland, OR.

“In every instance in which transformative art happens, it's never about individuals. It always happens in discourse, in relation, in exchange…”

“I don’t care about manifestos. I care about working with people that I care about and love, and having a common objective, and that objective is to create a space, an emancipatory space for everybody. Black people and everybody.”