Chapter One

This email conversation between Okwui Okpokwasili and Eva Yaa Asantewaa,* arts writer, curator and community educator, took place between March and April 2018.

Growing up in the Bronx, I was not very comfortable operating outside of the grid--outside of urban landscapes. I also felt certain about who belonged where, where I could go, what neighborhoods I could traverse safely. I didn’t feel free to go anywhere, to touch anything. In my neighborhood, there were large stretches of carefully manicured lawns that were accompanied by signs with clear instructions to “keep off the grass.” I was very much aware of limits and boundaries. It was in my imagination that I could take fitful steps towards crossing those boundaries. But even today, being in a wide-open field, or in dense forest or even standing at the shore and looking towards the horizon at a beach, underlying my feelings of awe, there is a strain of terror.

Nature was not something to be touched; in fact, nature was something you tried to keep from touching you. In the city, nature was covered in excrement, urine, broken glass. Touching could bring you all kinds of infection or, if nature was manicured and glistening and shiny, then you were admonished not to touch it, lest you infect it.

So, to be in Japan, on this farm, in a village, was to sink into the corporeality of nature. There was no escaping its touch. From digging potatoes out of the earth, or pulling worms off cabbage, I was constantly touching the earth or coated in it. So, for me, there was a continued unwinding of buried childhood terrors that accompanied any art practice.

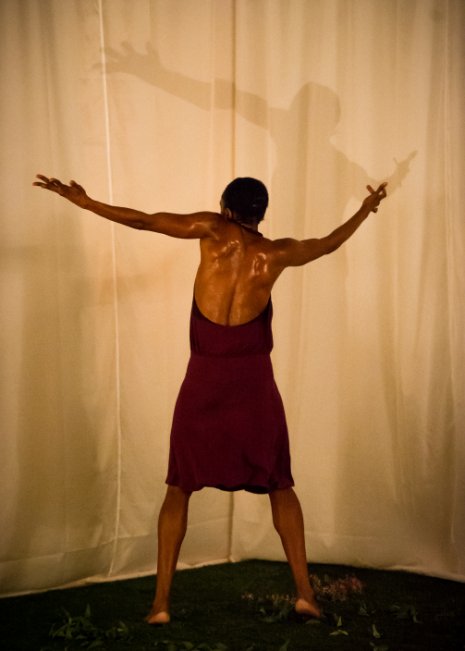

By this time, I was older and had already spent time in wilder wilderness, but I had never considered that in my performance practice the trunk of a tree could be a supporting partner. I had never imagined I could use the wind moving through me as a guide for flow. I was suffused with feelings of gratitude and respect. Pressing against the tree, dancing, my body might interrupt a procession of ants, and so they had to make their way across my body, and how could I not allow myself to become a willing bridge? Just as the tree didn’t rush to fling me off, I could patiently allow the ants to climb over me. I felt so lucky that the tree could withstand the weight of my body and, if my skin was bare, I’d even be imprinted with the pattern in the bark. I felt so grateful that the wind might push me to move in a direction I had not planned to go. With each inhale and exhale, I was taking my part in some great breath. My pores were open, my ears were open. It changed how I listened in a space, which directly impacted how I moved.

And all of this didn’t necessarily erase my fears but, somehow, the joy that accompanied my newfound gratitude could exist alongside some of the fears that hadn’t entirely subsided.

Perhaps it made me start to feel the presence of ghosts.

I think I’ve been really fortunate to work with people who understand the material of time. To work so closely with Ralph Lemon is to witness a preternatural patience coupled with a voracious curiosity. When he is building a score, or working with performers to build a score, he makes time. We might spend hours unwinding and undoing and reforming a phrase, getting underneath and busting open a phrase. In those moments, I had a feeling that time was being unspooled anew, that a minute was eighty seconds, an hour, one hundred minutes. It gave rise to a kind of spaciousness within me. The discipline of making time for myself and the performers who enter my process is very important to me.

I think, often, the economy of building live performance (limited rehearsal time, limited tech time, limited funds) builds a lot of pressure around time. Questions have to be answered, problems resolved and the end result must be predictable, repeatable and ultimately “known.” Of course, there are dance practitioners who reject this system of predictability or of clean resolve, practitioners who are interested in making structures that can contain the unknown and that ask performers to continue to make discoveries in performance, but they still have to contend with the time required to build a rigorous score, or a structure for improvisatory exploration.

Everyone is pressed for time. But time is everything. Time shapes the mind. It shapes the body and it feels like a radical act to take time and to hold a sustained attention to one act over time. When I do this, I feel I am witness to little miracles. I feel new interior landscapes emerge, and I traverse them into hidden memories or into new understandings. People who meditate know this (and I don’t know that I am one of those people), but to do one action over and over again, to pursue one task over an extended period of time, was my way of creating a miraculous opening for myself and for anyone witnessing it, an opening that would make it impossible to hold onto a position of certainty of who my character is, certainty about who the audience is seeing.

That quake provided an open road to new imaginings. In Bronx Gothic, my initial concern was to evoke a period where my relationship to my body felt unstable or my understanding of my body was unsteady and shifting, being in a state of multiplicity, seeing with a new understanding. I was interested in attempting to translate that condition in performance. Could this state be transmitted to the people witnessing the performance? A state of uncertainty regarding what they believe about my body and then in turn an uncertainty about what they believe about their own bodies? And in that uncertainty, a new pathway, a new understanding might be revealed?

How do any of us contend with the multiple conditions that are always present in one body? And when that one body collides with the complexity of the world, what is the resulting charge?

I was relying on my memory of pubescence as a time of confusion and dread where my body seemed to be housing an entirely other, unknown body within it, and that other, unknown body was working its way out of my former body. But there was also a sense of wonder. Could I, as an older woman, long removed from puberty, begin to excavate the conditions of that confusion coupled with wonder? And then, on top of that, what to do about bodies caught in a kind of purgatory? Bodies that have been violated in the middle of this transformation, bodies that were broken by violence and never properly pieced back together? I was interested in attempting to recall this confusion, and to be in a state of perpetual and obvious transformation and to be unfinished, to be in a state of multiplicity. How might that translate in performance, night after night?

I guess, the natural human state is to be unfinished. A friend was sharing something very wise with me earlier, a quote from Pema Chodron:

“As human beings, not only do we seek resolution, but we also feel that we deserve resolution. However, not only do we not deserve resolution, we suffer from resolution. We don’t deserve resolution; we deserve something better than that. We deserve our birthright, which is the middle way, an open state of mind that can relax with paradox and ambiguity.”

To be human is to live within a veritable kaleidoscope of contradictory and constantly shifting modes and truths. And how much more so is that for someone who has survived violence and trauma?