Chapter One

This email conversation between Courtney Bryan, in New Orleans, and musicologist Matthew D. Morrison*, in New York, took place between March and April 2018.

- Matthew D. Morrison, PhD

Performance and composition do indeed feed into each other regarding my process. When improvising, I practice the skill of spontaneous composition, to borrow a term from Gary Bartz that he shared with my African American Music history class at Oberlin Conservatory. When notating a composition, I use the approach that Wayne Shorter explains, “Composition is just improvisation slowed down, and improvisation is just composition sped up.” I agree.

I admit that while simple, the act of translating these processes can be difficult. For a while my notated music and my piano improvisations sounded like different music altogether, but as I get more comfortable with my process, especially towards notating exactly what I am conceptualizing, the two modes of producing are beginning to yield more similar results. Because composing through notation is a slowed down process, I have space to explore ideas that I would not automatically have at the piano. For example, I like to experiment with visual symbols and shapes in a written score and can then use this approach when improvising on piano. As an improviser, the process from my ear to my hands feels most comfortable, and I like to translate that act - of what I would do in the moment when completely present in the music - to music that I notate. I want whatever I do in any context to be alive and present. That is my goal, and performing and composing help me find fresh ways to do this.

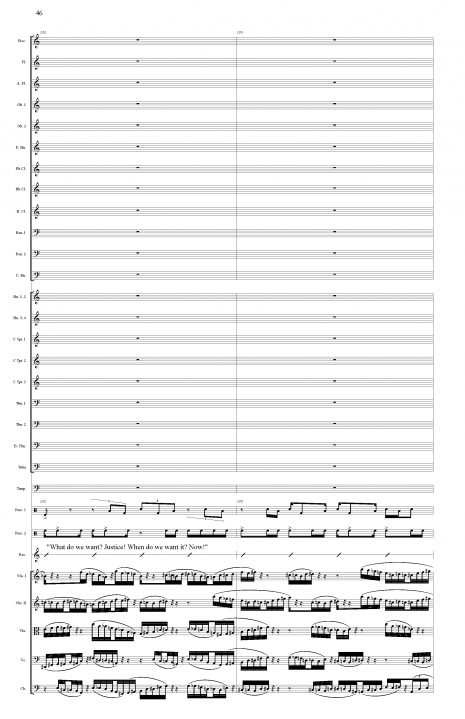

During one of my first composition lessons with our professor George Lewis, I remember him offering the idea that my main project was to notate improvisation. At the time I was not sure exactly what he meant. I became focused on this idea of notating the ‘feeling’ or ‘spirit’ of improvisation when I participated in the Jazz Composer Orchestra Institute, co-sponsored by Columbia University and the American Composers Orchestra, held at UCLA in 2012. As a result of this program, I had a reading by ACO of my piece, Shedding Skin, for orchestra (2013), along with other composers who shared the goal of including improvisation and the orchestra. In this piece, and in my pieces to follow for chorus, orchestra, and other settings for non-improvising musicians, I try to notate exactly what I am hearing, which often includes drawing from influences that are not always played by a certain instrument in a specific setting. For example, if I were to hear gospel musician and pastor Shirley Caesar’s voice as a collection of horns and strings, what would I notate?

In other cases, I have written more time-based scores with a mix of traditional and non-traditional notation so that the performers add elements of improvisation without the score suggesting a certain style of improvisation. An example is the piece I wrote for three gospel choirs for kara lynch’s invisible :: meet me in okemah :: saved. (The three choirs included First Corinthians Baptist Church Choir and Director, Dr. Patrice Turner; Convent Baptist Church Choir and Director, Professor Gregory H. Hopkins; and Bethany Baptist Church Choir and Directors, Rodney Smith and Lillian Whitaker). I notated a collective wail for the choirs based on an improvisation by IMPACT Repertory Theater and team leaders, Deitrice Bolton and Carlton Taylor, who were a key part of the collaboration. This notated wail was written in a way that the choir directors could use their traditional practice of teaching from a score to church choirs where some read music and others learn by ear. There are skills that church directors use in teaching music to choirs that have diverse ways of learning music. I wanted to draw upon that process while leaving space for improvisation, and, as I marked in the score, for “the spirit to lead.” This notation included traditional notes, written instructions, symbols, and general timing instructions. I believe this process was successful.

Often in my collaboration across the arts, I use a mix of these notational processes for the other musicians, once again depending on their background and what type of notation I feel would be most comfortable for all involved. I have not yet developed notation for what happens between the music and the other art forms, and don’t know if that would be necessary unless I was composing all the aspects of the piece. The beauty in collaboration for me is to share control and vision, though I do wonder what communicative value notation between the art forms would have. When writing for improvisers, I tend to notate the core elements of the piece, including melody, chords, any specific figures that should be exact, and clearly mark areas for solo or collective improvisations. Usually in this case, I am writing specifically for particular musicians, and the music is based on what I love about their unique voices.

Your response points to your practice and commitment to composing for a diverse range of ensembles and performers—whether a big band, new-music group, or improvising harpist. This eclectic skill as a composer of classical, jazz, and a diversity of improvised music is often threaded by how you engage with technology in your works. As we live fully immersed in the digital era and rapidly changing technologies, how does technology and music intersect in your work as an eclectic composer of improvised, western (classical), and jazz in single compositions? It is a uniquely sonorous mélange that contributes to what might be referred to as a ‘cosmopolitan’ style of contemporary concert music.

In my recent works, I have been very interested in creating music that draws from the experience of social media. This includes the way we communicate, receive news, celebrate, grieve, and make jokes in our daily interactions on social media.

In my piece Songs of Laughing, Smiling, and Crying (2012), I used YouTube as my archive to collect recordings, and mostly live recordings or films, of pieces with the themes of laughing, smiling, crying, or clowns and circuses. The pieces range across genre and time periods. This was a direct impact of sites like YouTube and how accessible all of this music is for us today. I turned this into a composition where I could improvise on piano with all of these recordings, along with help from sound engineer Bill Lee. I could virtually collaborate with Louis Armstrong, Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, Dinah Washington, Placido Domingo, and Tupac all in the same piece!

I used the same process with a different inspiration when I composed Sanctum for orchestra and recorded sound (2015), sampling the voices of Marlene Pinnock, protestors in Ferguson, MO, and recordings of sermons by Pastor Shirley Caesar and Rev. C.L. Franklin. During the process of collaborating with poet Sharan Strange on Yet Unheard for orchestra, chorus, and Helga Davis (2016/17), I composed a piece, A Presence, that includes manipulated sounds of Sandra Bland’s voice from her podcast series, Sandy Speaks, and my improvisations on piano.

The works you’ve mentioned live in the virtual world, but they also live in the reality of societal injustices—particularly within African American communities. Specifically, in 'Sanctum' for orchestra and tape, you directly address the disproportionate impact of police violence on black communities and the rise of #BlackLivesMatter protests and social media efforts that continue to stir the nation since the death of Trayvon Martin in 2012. How do contemporary events in society impact your artistic choices? How do the artist (composer/performer) and activist intersect in your work?

Too often, we are confronted with stories of people being victimized by police, and, in most cases, these victims do not receive appropriate justice. It is a traumatic series of situations to take in, even from the screen of a computer. I am inspired by all who have taken to streets and to government offices to protest for justice and change. My personal response is to deal with the emotions of these events through my music. Some of the sounds that I use come from the videos I see on my computer or on television, some come from people around me, and other voices come from recordings from earlier times. Then there are the sounds of acoustic instruments, which I use as a palate to illustrate what I am feeling and thinking. Whether or not this is activism, it is something that I hope can give listeners a chance to feel their emotions, regardless of their political viewpoints.

I described earlier how I use recordings in Sanctum. In another composition, Spirits (2015), I also use recordings as inspiration. I start the piece vocally quoting John Coltrane’s voice, “May there be peace and love and perfection throughout all creation, O God,” as quoted in Alice Coltrane’s The Sun from her 1968 recording A Monastic Trio. Then I proceed to perform what goes from sounding like light rainfall to a storm in the lower range of the piano. Whether solo piano or with other instruments, this is the rumble that is present in my recent works, a dense saturation of sounds. Towards the end as I introduce other melodies, I read the names of various victims of police brutality. Each time I have performed it, there are unfortunately different names to add, so I choose a few, alternating between men, women, boys, and girls.

The largest piece I have written is Yet Unheard for chorus, orchestra, and vocalist Helga Davis (2016/17). It is the largest in size, but also in scope: it draws together composition, collaboration (with poet Sharan Strange and vocalist Helga Davis), and social justice concerns. Yet Unheard was commissioned by The Dream Unfinished: an activist orchestra, founded by Eun Lee, to honor the one year anniversary of the death of Sandra Bland, and the premiere was a fundraiser for social justice organizations supporting African-American women victims of violence. The second performance of this in a chamber version was by invitation of Vijay Iyer at the Ojai Festival in 2017, and a third performance with the original instrumentation will take place with Steven Schick and the La Jolla Symphony this June.