Chapter Three

LCT:

You have often worked with children. Childhood is often reduced to a cliché, whether one of beatific innocence or a kind of agnostic dystopia, in film and art alike. Your representations of childhood and adolescence, in “Goshogoaka,” “Pine Flat,” “Pódworka,” and “Rudzienko,” are quite different, often imbued with a sense of fragility, vulnerability, and complexity, all at once. What has drawn you to children and teenagers? What have you drawn out of them, and they of you?

SL:

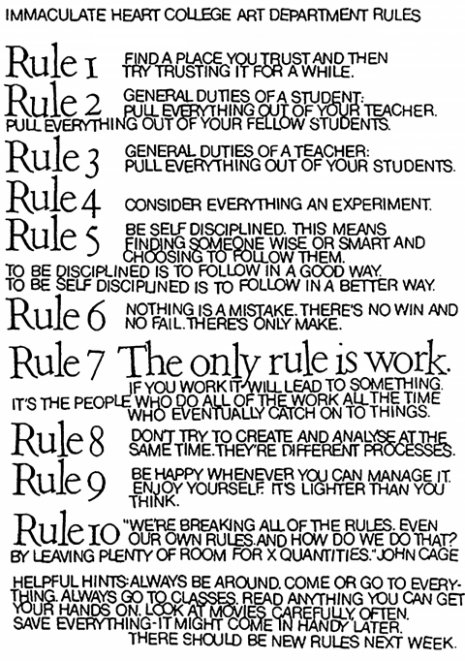

I really like the way you phrased that question. It reminded me of one of Sister Corita’s rules. To paraphrase, it goes something like, “give as much of yourself and draw as much as you can from others.”

I don’t think I am unique in my representations of childhood. It is a hugely popular topic today and so I think, like any subject that is widely represented, there are representations that oversimplify in order to get their point across. Of course I read as much of the theoretical and historical background as I can, and look for under-represented histories and forms like the Korczak stuff. I would hope that my strategy for dealing with the subject is similar to some of the work that inspired me: Truffaut’s work with children, Jean Eustache’s “My Little Loves,” or Kiarostami’s “Where Is the Friend’s Home?” I want to be as honest as possible with kids and have them relate to me on a level that is equal. Children are just as complex and multifaceted as adults. I think one of the elements that has drawn me to them is that they are just more honest. They engage with the world in a much more straightforward way, often without some of the preconceptions that adults have. This is why it is often possible for adults to see through a child’s motivations. Children have a harder time hiding and they have less interest in doing so. I have always just naturally drawn children to me and had an easy time relating to them. Something about me makes me hard to place for them. They think I don’t behave like the other adults in their lives and so they engage me as their equal. For instance, when I was doing “Pine Flat” I was always around town in the middle of the day, I didn’t have a spouse with me, I always walked instead of driving, I wore t-shirts and overalls, and I was willing to play with the children. None of this replicated their parents’ lives and so they saw me as more like them. This has allowed me an access that might be more difficult for others. In my first visit to Poland, I remember walking up to children in the courtyards and they would just start talking to me in Polish and I’d answer in English and I don’t think either of us understood what the other was saying but somehow we communicated.

I think the more difficult part of your question is what they draw out of me. The answer may be the flip side of their unintentional honesty. Children can sense all the BS instantly. They can tell if people aren’t being straight with them and they will shut down as soon as they sense it. Maybe this has been part of the success of my work with children: they require a kind of honesty that I feel I have to hold myself up to.

That children are comfortable with the idea of play is also something that draws me to them and has rubbed off on the projects I do with people of all ages. Play is important for all my collaborations. Whether it’s a middle-aged farming couple or ship fitters in Maine or kids in Poland or America. I think I told you the story before about how when I returned the lunch boxes to the workers in Maine (I shipped them in the mail from LA after I finished photographing their portraits), we filled each cooler with Halloween candy and treats. The boxes arrived on the workers doorsteps on Halloween and I know they enjoyed it very much. Laughing is important, as is being foolish and being physical.

Looking back, I’ve realized that a lot of what I do with children is physical. As I mentioned before, I was recently invited to give an artist’s talk on Steve Paxton who founded Contact Improvisation and was a co-founder of the Judson Dance Theater. I realized in the early research I did for “Goshogaoka” how much Paxton had influenced me. His approach to movement as way of interacting and creating interpersonal relationships was so helpful, as were all the Judson choreographers’ attention to everyday movement. It changed the way I looked at movement and gave me new ideas for how to use it. The physical stuff really helps to break down barriers and helps communication. When I can’t speak the same language as a young person, I find I can just start playing with them, doing something physical, like the game “Red Light, Green Light,” and pretty soon we are on the same page. I saw that recently when I reviewed footage from the farm in Poland last summer. I am in constant motion with them and organizing their movement. It’s led me to plan the next summer’s workshops around the body and movement.

LCT:

Many of your works, including “NO,” “Lunch Break,” “Double Tide,” and “Exit,” depict the rituals and repetitions of labor. What do you think it is about labor, and laboring bodies, that attracts you, and how have you sought to represent it?

SL:

Most of the world’s people are laborers and without that work we would not have the kind of world we do. Growing up in a working class family, I have always felt a connection to physical labor and to an engagement with the world that is more physical and less intellectual. (Perhaps this is also an answer to the previous question about children. Their engagement with the world is also physical.) In “NO” and “Double Tide,” the experience of making the films and the kind of labor engaged in were so elemental. I loved being in nature and I really identified with that kind of work. The months of scouting and learning about their processes were so satisfying and getting to know the people was equally great. In both cases, the subjects’ commitment to the natural world and knowledge about it was inspiring. I think you are spot on when you spoke of the rituals and repetitions of labor too. There is something that is so simplifying about labor, having the same schedule and rituals that is an antidote to contemporary life. It creates the space for certain kinds of relationships as well. The workers at BIW [Bath Iron Works] have known each other for years in a way that I think is less and less common. At the diner across the street from the plant I talked to customers and waitresses who have seen each other every day for 30 years.

***