Beyond Entertainment

MD:

Like early American democratic thought, tap dance is, itself, revolutionary in origin. That African-American slaves and Irish indentured servants came together, blended cultures and manifested a democracy and a ‘freedom’ that wouldn’t be seen politically for over a hundred years is extraordinary. Tap dance has influenced everything from jazz music to bboying and hip-hop. Its history is a powerful reflection of the history of the United States – from extreme oppression to joyful expression and back again.

What we’re chasing away with this education are stereotypes, mis-education, racism and deep-rooted snobbery.

We are simultaneously fighting against images of minstrelsy, and of the movie musical as two different, both inaccurate ways to “define” tap dance in American culture.

We are fighting against those who think the form is too presentational (Broadway) or not presentational enough (Savion Glover’s heavily criticized back turned towards the audience).

We are fighting against those who consider the form to be purely entertainment and not art, as well as those who think it’s musical sensibility is not accessible and too daunting for a mainstream audience.

My dream is spreading a love and respect for the art form as it is, while chasing the possibilities of what it can be.

Tap dancers have two huge worlds at their fingertips. We are simultaneously dancers and musicians, and I take my responsibility to those two worlds very seriously. I chase finding the potential in both without compromising the integrity in either.

MBJ:

And who would you name as your allies in this journey?

MD:

There are so many brilliant hoofers/tap dancers/choreographers/artists out there – killers - who are innovative and pushing technical ideas on a daily basis as soloists. Those dancers inspire me to take risks choreographically and push myself technically. They are my allies. They are my friends, my peers, my elders, and they inspire me constantly.

The spirits of hoofers like Gregory Hines, Jimmy Slyde, and Harold Cromer, the great women of the tap renaissance, mentors like Gene Medler and Dianne Walker, innovators like Brenda Bufalino, risk-takers like Josh Hilberman, dancer/directors like Ted Levy, master technicians like Sam Weber, visionaries like Mark Mendonca, revolutionaries like Savion Glover. My allies are also musicians and composers of many genres, like the brilliant Toshi Reagon, curators, multi-form dancer/choreographers, presenters and artistic directors like David Parker, Judy Hussie-Taylor, Ella Baff, David White & Alison Manning, Janet Eilber, Brian Green, and Ephrat Asherie. My allies are artists who share the stage and creative collaboration with me: Dormeshia Sumbry-Edwards, Derick Grant, Nicholas Van Young, Jason Samuels Smith, Miriam Chicurel, Aaron Marcellus, Greg Richardson, Darwin Smith, and every single one of my dancers.

MBJ:

You've built a career in the study and generation of sound. Where is your quiet place? Are you able to enjoy silence without mentally filling it with rhythm?

MD:

My quietest place is often filled with music and sound. The richest noises in nature often fill me with quietude and peace the way the purest of silences cannot. Sounds and presences like the ocean, its constant waves crashing or crickets and cicadas in the North Carolina woods at night. These things can bring to rest the incessant rhythms living/building in my head.

The city usually only incites or inspires music and rhythm but I have to admit that the distant hum of the BQE [Brooklyn-Queens Expressway] can lull me to sleep. Some of the most exceptional quiet places for me are songs that I don’t want to touch, songs that I can just lose myself in without a percussive or musical thought or interruption. To me those songs are magical.

MBJ:

Can you recall a moment, either in a rehearsal, in a jam session, or on stage in front of an audience, where you were part of an ensemble that achieved complete sonic synchronicity? Five dancers or more achieving oneness in sound? Can you describe the feeling of knowing oneness when you hear it? Is sonic synchronicity the same as perfection in sound?

MD:

I most definitely have felt the power of oneness with an ensemble. I cut my teeth performing with the North Carolina Youth Tap Ensemble where sonic synchronicity in each work within our rep was one of the highest achievements we could strive for. This has happened only a few times in a few different settings in my adult life but that feeling of oneness did not always manifest while executing solely unison choreography and unison sound.

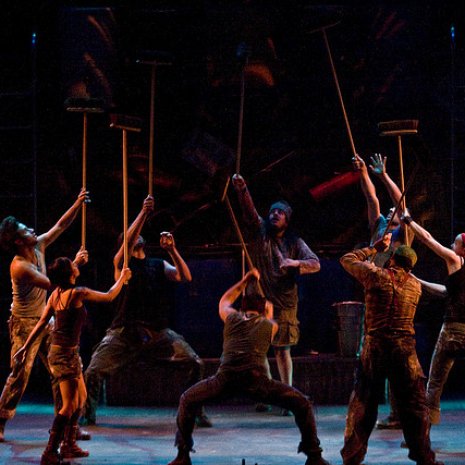

One of my favorite examples of this is the kind of magical synchronicity that happened in STOMP. Of course, I sought that level of execution and that connection every night, but only rarely were those moments of complete perfection possible. This is because they are so much more than sonic, percussive or musical. Those moments are spiritual and energetic. Oneness could only be achieved when everyone in the cast was vulnerable to each other.

In THAT moment, when each individual willingly gave him/herself over to the group, when breath and muscle became one with time, pulse and groove, in THAT moment we could lock in. In THAT moment, we came out of an 8-part polyrhythm into total unison, complete oneness. It’s so powerful that it changes your physical experience, it can give you goose bumps, it can take your breath away. I could never call this kind of sonic synchronicity “perfection in sound” because it is so much more than sound.

That oneness isn’t heard, it is felt.

""What we're chasing away are stereotypes, mis-education, racism and deep-rooted snobbery.""

""The oneness isn't heard it's felt.""