Science, Knowing, Magic

Thanks to curator Pablo de Ocampo* for his email interview conversation with Deborah Stratman conducted during March and April 2014.

Pablo de Ocampo:

Deborah, I’m really thrilled that you’ve been recognized with this award as I’ve been a huge fan and supporter of your work for some time now. I wanted to actually begin by asking a question I use when leading workshops and talks about cinema, which is to ask you to share a memorable or defining moment you have of watching a film. I don’t so much mean the film itself, but something about the experience of watching it: the context, the architecture, the weather, etc.

Deborah Stratman:

I was in the cinema with my family watching Dumbo when my mom went into labor with my youngest brother, Dave. I guess I would have been about nine. That was pretty memorable. Especially since my brother was arriving two months early. Dad’s good at kicking into efficient triage mode during chaotic, stressful scenarios, so all came out fine in the end. But we had to leave the film when things were still really grim for Dumbo, before he realizes he can fly, which I recall was very troubling.

In terms of defining my practice, one of the more memorable experiences was circa 1987, taking a class with Peter Kubelka. I was an undergrad, just transferred to art from what had been a physics trajectory, and I had no idea who he was. He projected his film Unsere Afrika Reise from a flatbed for the entire semester, breaking it down cut by cut. It was a radical immersion in synchresis, contextual slippage, transplantation, manipulating temporal pressure, choreographing the gaze… basically, a cinematic grammar 101. It instilled in me a love of something beyond literary or theatrical tropes, a kind of pure cinema.

PdO:

We've talked before about the idea of suspension in relationship to your film Kings Of The Sky and I wanted to revisit that idea and ask you to respond to that idea in the broader context of your work. I'm thinking here both of other direct visual images – like your use of Niagara Falls in "O'er the Land" – but also of suspension as a phenomenological experience of sound that permeates so much of your work.

DS:

Suspension, yes. It’s a resilient theme for me. I think about it on a number of registers, many of which seem to make cinema possible.

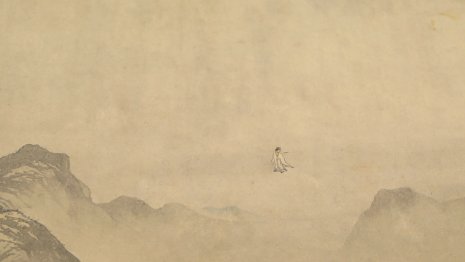

Suspension of belief. Suspension of time – internally to the film, how the filmmaker stretches and compresses it, or externally, when viewers relinquishes their personal time to enter the film’s. I think about suspension in terms of gravity, or when gravity is resisted. The story of Colonel Rankin in "O’er the Land", for instance. Or the levitating man who appears in Immortal, Suspended, in the center of T’ang Yin’s painting. The title of the painting suggests that he is levitating because he is immortal, and so outside of time. I think of suspension in terms of a cut, where an action is arrested, so not subject to the normal laws and forces that affect bodies. But it could also be, as you suggest with the Niagara Falls shot, a durational experience that changes yet remains the same – an image that aspires to the condition of a drone.

Then there’s suspension as preservation, bugs in amber or objects in museums or ideas in books. And suspension as cessation, whether the stoppage be permanent or temporary. When I consider it this way, I start recognizing suspension as a potential force, like with a general strike.

Of course, there’s also the phenomenon of suspense, one of the primary engines of cinema, and sound is extremely facile in this realm of tension building. I love audio for its capacity to manipulate our expectations, but also for how it somatically evokes place. I hear grasshoppers, a distant lawnmower, kids playing, leaves moving in the wind, maybe a far away plane…and I effortlessly imagine a hot summer afternoon, sitting in the prickly grass. Incidentally, sound can be used to levitate objects! It’s called acoustic levitation. Small objects placed in the crosshairs of oscillators on x-y-z axes get trapped in the wave pattern and appear to float.

PdO:

Acoustic levitation! Your knowledge base continually amazes me. It's something that is so striking in your work, the way in which you draw on these expansive systems of knowledge, both scientific and worldly yet create work that seems to transcend knowing. This acoustic levitation idea is such a perfect example of that, capturing this slippage in which scientific knowledge and magic come together. Could you talk more about this idea of slippage?

DS:

That’s nice to hear that the work can transcend knowing. There’s a thing the writer Charles Bowden says that I’ve quoted a thousand times, but it never stops inspiring me. He says what is explained can be denied, but what is felt cannot be forgotten. While I love exploring and thinking about different paths of knowing, or just research in general I guess…I don’t want my art works to espouse a known. I’d rather they reflect the process of investigating and feeling things out, even when that process is unwieldy or difficult. I deeply admire the structures and laws that scientists spend their time formulating, but I equally want from experience a place of unknowing, like what Keats called ‘negative capability,’ when he’s advocating for beauty over categorical knowledge. He describes it as “when a man is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.” I think my attraction to chaos and entropy is related. There’s something so powerful and cleansing about destruction, even when it’s agonizing. The paranormal or magical keeps showing up in my work because it represents phenomenon that are felt but can’t be explained. And the science turns up because it’s so elegant and cool. It’s inspiring to me, the quest for universal patterns just for their own sake. The slippage exists because both paths, the scientific or the poetic, have wonder and observation at their core as catalysts.

PdO:

Yes! I love that Bowden line which I've heard you say before, particularly this notion about that which is felt not being forgotten. This resonates for me in many of your films through this intense visceral quality that you are able to induce through the otherwise immaterial means of cinema. This physical impact, or resonance, becomes obvious in some of your work outside of moving images, like the sound sculpture environment Tactical Uses of a Belief in the Unseen, a project where one's body is literally shaken by sonic frequencies. But I think it has a very strong presence in your films, this awareness of a being a physical body in the world.

DS:

Immateriality is such a fabulous container. I like it for art making because it allows a person, much more so than if they’re making collectible, material containers for their ideas, to sidestep the commodity value of objects. Not to mention where the heck to keep all that physical stuff. Of course there are films that operate more like objects, limited edition prints, film installations, etc – where the material becomes salient. But generally speaking, a film isn’t a thing; it’s an ephemeral constituent. As a whole, it only exists in your mind. You can freeze its unfurling, and examine a frame, or play it in repetition. But in order to consume and grapple with the film in its always-moving-past entirety, the collaboration must be with memory and with expectation. The film lives inside the person. Its very immateriality is what makes a visceral, embodied reception so exciting, or maybe what makes it possible. I think it has something to do with desire. The fact that we’re not seduced by what we have, but by what’s absent. So we reach towards this slipping past, non-corporal thing, and project our own bodies into it. We are absorbed by it, or wear it, like psycho-dramatic camouflage.

Emotional and social resonance is possible in all kinds of work, of course. We become aware of being a physical body in the world when we’re doing, moving. And if we’re not doing - if we’re sitting in darkness, watching - then maybe we sense our physical being when we’re made aware of how we see and how we hear. What are the channels we absorb through? How are we prevented from seeing and hearing? To be aware of our own agency, or lack of, is a deeply political embodiment.

*Formerly Artistic Director of the Images Festival in Toronto, Pablo de Ocampo was recently appointed Exhibitions Curator at the Western Front in Vancouver. In 2013 he was the Programmer for the 59th Robert Flaherty FIlm Seminar. He has organized and curated screenings, exhibitions, performances and related events at cinemas, galleries, festivals and arts spaces internationally. In 2003, he co-founded the collectively run screening series, Cinema Project in Portland, Oregon.

Curriculum Vitae (PDF)

""A film isn't a thing; it's an ephemeral constituent.""