In Marie's Words...

I am a member of the Seneca Nation, and my work draws on images and ideas from Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) protofeminism and Indigenous teachings. My practice is interdisciplinary, incorporating printmaking, painting, textiles, and sculpture. Some of my projects are solo in nature, while others are collaborative. In all of them, I explore how history, community, and storytelling intersect.

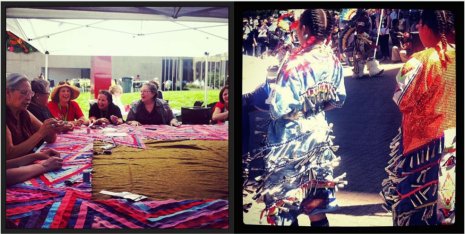

A significant part of my practice involves setting a table for people from different backgrounds—multi-generational, cross-cultural, trans-disciplinary to come together and connect. This can take the form of sewing circles, community-built sculptures, or crowd-sourced participation in a project via social media. In my sewing circles, I appreciate that each person’s stitch is like a signature or thumbprint, and that as the stitches intersect, they become a metaphor for our relatedness. Stories flow while eyes are diverted and hands are busy. I believe that exchanging ideas like this, one story at a time, can help us understand and strengthen what I call our companion relationships—our connection to place, to one another, to animals, and to the universe.

This interconnectedness lies at the heart of my practice. There is a question I return to throughout my work: What would the world look like if we thought of ourselves as companion species? It comes out of my reading of the Seneca creation story, in which animals are our First Teachers, and I’ve explored it in my ongoing series Companion Species (2016–), which includes embroidered wool blankets, a cedar sculpture, cast bronze and crystal pieces, copperplate etchings, and wood-block prints. At first, the series focused on canines who have lived in close relationship with humans as our pets and literal companions throughout history. As I studied depictions of dogs in art history, I was struck by an image of the Capitoline wolf nursing the Roman demigods Romulus and Remus. Here was a vivid example of the connection between the human and animal worlds—a canine mothering humans, nurturing and protecting them with her body even though she wasn’t their biological mother.

The Seneca are a matrilineal society, and the word “mother” has great significance for us, referring to our inherent responsibilities not only to other humans, but also to the nonhuman world of plants and animals, land, and sky. I believe all humans have maternal qualities that can help bring about balance in the universe if we are willing to prioritize them. While listening to Marvin Gaye’s 1971 anthem “What’s Going On,” I began to contemplate the lyrics “Mother, mother,” “Brother, brother,” “Father, father,” “Sister, sister.” Gaye’s words invoke our relationships with other humans, but in an Indigenous world, this call would extend even further: “Uncle, uncle,” “Grandmother, grandmother,” “Deer, deer,” “Water, water.”

As part of the Companion Species series, words are hand-embroidered on reclaimed wool blankets highlighting the intersection of Gaye’s knowledge and Indigenous knowledge about our relatedness. Language—especially “twinned” language, or call-and-response—often appears in my work. It calls back to the ancestors and forward to future generations, acknowledging the wide circle of relationship we are all born into.

Call-and-response is also central to the project I plan to work on over the next three years: a series of site-responsive neon sculptures that will blaze like a sunrise on a shared horizon as they amplify the text TURTLE ISLAND. This series will be called Chords to Other Chords (Home), after a line in Joy Harjo’s poem “Bird.” For the Seneca and other Indigenous peoples, Turtle Island is the name of North America, or planet Earth. Native peoples are often expected to translate our stories for those outside our communities, but this name will be placed in the landscape without explanation, subverting expectations while affirming the importance of the ancient story of Turtle Island. Perhaps saying the place-name “Turtle Island” can change the way we steward the planet and human relationships?

These sculptures will be sited at prominent arts and cultural institutions in New York State. On a poetic level, the signs will call back to the ancestors and forward to future generations. On a practical level, they will provide a platform for integrated programming in each community, with a focus on initiatives concerned with Indigenous language, environmental stewardship, and the preservation of traditional foodways, music, and storytelling.

I envision the sculptures growing larger in scale and more collaborative in scope over the next decade, as I plan to work with choreographers and composers, as well as the broader community. I am interested in exploring how sculptures are activated as a result of living in the world, and how different types of activation promote seeing through a multi-sensory lens.

I am an artist as well as a custodian of stories. I believe I have the responsibility to amplify the stories of others, set right historical blind spots, and speak up for those who can’t speak up for themselves: humans, animals, the natural world. My materials also tell stories. Many of the ones I use—blankets, beads, tin jingles—are associated with my Seneca heritage, and are considered “nontraditional” or “craft” materials within the context of the Western art world.

Blankets

Blankets are central to my practice, and I return to them again and again, as canvas, medium, and subject. In my family and tribe, we honor people for being witness to important life events by gifting them a blanket, and I appreciate that this is a custom shared in common with other Indigenous communities. Blankets receive us into the world and accompany our departures. We constantly imprint our energy and experience onto these humble objects. Blankets also played an important economic role in trade between Native peoples and European settlers. After I came across a photo of a 1913 Coast Salish potlatch in which a blanket is seen flying through the air like a magic carpet, I began to think of them as transportation objects as well, capable of carrying meaning and memory through time and space. The blanket is a witness to all aspects of human experience, both momentous and mundane.

In Companion Species (Canopy) (2016), large tapestry pieces made from reclaimed wool blankets hang and hover in the center of the space. Their scale is enveloping, and the blankets themselves, irregular in shape, have performed the work of second skins, covering, protecting, and insulating bodies on beds and couches, at campfires, and between migrations. The former presence of a body, or bodies, is suggested in the mended bits, worn bindings, and stains, which to me are like beauty marks. A shift in airflow triggers the slightest movement in the cloth, a reminder that it’s a living material.

Cedar

Images of my work don’t convey the scent of cedar that is a large part of experiencing Companion Species (Underbelly) (2018), a sculpture of a canine that weighs one and a half tons and measures 15 by 10 by 11 feet tall, towering over viewers even as she exposes the most vulnerable part of any animal’s body: the underbelly. Displayed in a gallery space where her dimensions exceed the width and height of the door frame, she is like a ship within a bottle. The cedar she’s made from suggests a continuum with nature, and her scale questions Western notions of dominion over animals.

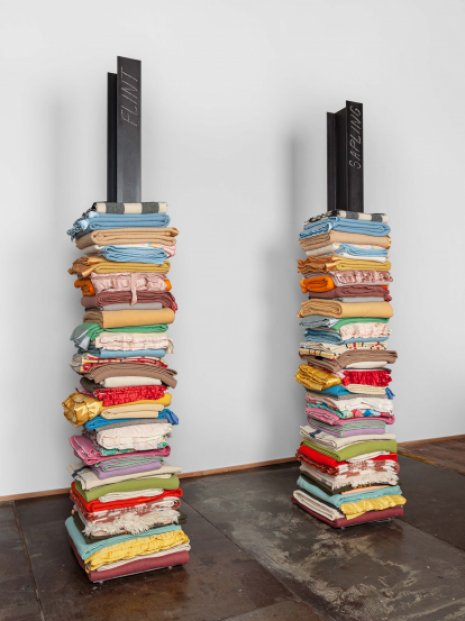

I-Beams

My use of I-beams in pieces like Skywalker/Skyscraper (Twins) (2020) acknowledges the labor and skill of the Haudenosaunee ironworkers, or “Skywalkers,” who helped build New York City skyscrapers like the Chrysler Building and the Empire State Building in the early to mid-twentieth century. My I-beam supplier, Abe, tells me that iron is the most recycled material on the planet, meaning it’s likely that the I-beams I use embody some aspect of my ancestors’ presence. Columnar and ladderlike, I-beams bridge the earth and sky. They evoke skyscrapers and steeples, reaching skyward like trees to light and channeling a warmth that contrasts with their cool, still disposition.

Tin Jingles

In pieces like Butterfly (2015), I use tin jingles to reference the jingle dress dance, which originated in the Ojibwe tribe during the influenza pandemic of 1918. The story goes that a young girl was very sick, and her grandfather had a dream in which he was instructed to attach the jingles to a dress. Women wearing the dress then danced around the sick child so she might be healed. The belief was that the jingles made a healing sound. We can assume the medicine worked, because other tribes adopted the practice, and the jingle dance is still performed at powwows today.

Tin jingles are activated by touch, light, and movement.. Nestled side by side, shiny and familiar, they beg to be activated. Before I sent the jingle clouds that make up Sky Dances Light (2023) to the gallery to be displayed, it felt important to activate them, to imbue them with intention. I invited Acosia Red Elk, a ten-time world champion jingle dancer from the Umatilla tribe, to dance with the jingle clouds. Her interaction with the sculptures affirmed something I’ve long felt: that these materials are alive, and part of their aliveness is the way they’re engaged through dance and touch and sound. The jingle sculptures shift with the brush of a hand or a passing breeze, just as our understanding of each other expands and deepens when we create opportunities to connect. Or, as Klamath elder Gordon Bettles says, “My story changes when I know your story.”