Chapter Two

You bet. America is a big obsession is mine. I am amazed by the depth and skill with which Rodgers and Hammerstein’s musical gets at questions of how America defines itself; the role of the outsider, the need for an outsider, and the cost of that need. Who Left This Fork Here started out with a rehearsal of Chekhov’s The Three Sisters, and over three years of working on it on and off, it became something else entirely. And yet not: I was thinking about aging and mortality. My father was ill at the time and I spent hours at a time just looking at him. I was thinking about the human face. In Fork, Jim Findlay and I made use of very low-tech live video that allowed the audience to look close up for a long time at the face of Judith Roberts, who was 80 years old when we made the show. I asked Judith to sit and look at her own face in the camera’s monitor— that alone was her action. So the audience watches Judith watching herself.

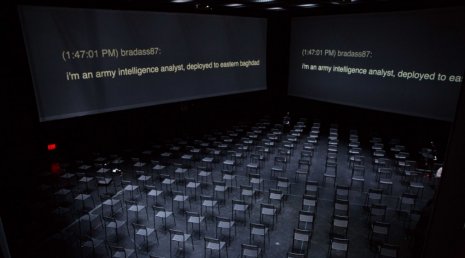

Faces also made up the visual content of The Source. In this piece, which concerns Chelsea Manning and the documents she released through Wikileaks, the composer Ted Hearne set excerpts of de-classified U.S. military documents from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan to be sung by four singers and played my seven musicians. Novelist Mark Doten arranged the text. Jim Findlay and I filmed about a hundred people - who were not performers - watching a U.S. military video of combat in Iraq. (The video is known widely as The Collateral Murder video). The faces of these people were projected on large screens that surrounded the audience on four sides. Again, the audience watches others watch, and in the end, they watch each other watch the collateral murder video.

Looking to discover something -- about what it’s like to be a human being. I think of those plays as new plays. But it strikes me as odd to refer to a production of a play by Shakespeare as being contemporary— how could it be anything but contemporary? It’s happening now. When a production of a play by Shakespeare is really cooking, one senses the words are being invented, spoken for the first time and the actors seem like expressions of the text itself, not interpreters of it. The play speaks the actor. It’s like great rock’n roll. Or a great symphony orchestra in concert. There’s a sense of presence and total authenticity; it feels at any moment like the whole thing might spin out of control and the blow the roof of the place.

It’s a quality I aspire to; I can’t say it’s one I achieve, certainly not all of the time. It’s elusive, kind of internal and I depend on the preparedness and courage of the people I work with, especially actors, to go there. I ask a lot of them. They endure long periods of saying something or working on something not knowing what it means or why they are saying it or what we are moving toward. I've been told that the process can be pretty intolerable at times. I’m uncompromising about them being real and vulnerable in space and time. I know that's not an answer about staging, but the two are bound up together. Back to staging…

I try to make space for people to find their own meaning in. I’m interested in people being simultaneously alone and together in the same room. For The Source, this was overt-- there was no physical distinction between audience and stage (the singers sat among the audience; everyone is onstage and/or everyone is being watched). For Oklahoma!, the seating was arguably the main element of the design, and the audience witnessing the story became part of the story. But it’s there in proscenium work as well. The stage and the house make up one room. That seems to me to be maybe the one inarguable fact about the theater: We are all here now. In dance people never question this. Same with sculpture. But in theater, there is a history of, well, being fake. Do you find your students subscribe to this?

These trends move in cycles, in reaction to what’s come before. For a while now artifice has gotten a bad rap, but maybe that’s changing.

If only our political predicament was momentary. I’m not very reassured that theater can change that. It can offer us the chance to be more alert, to slow down and look at people, things and situations more generously than we might. It can inspire the questioning of authority and independent thought. So I think there is an indirect political/cultural power there. It can also distract us and make us complacent. And this is all just what happens inside a theater between the stage and the audience. The extent to which any of us carry the experience outside is tenuous at best. Harsh as that may sound, it doesn’t make me want to stop. I am super lucky to be a director and make work that I love. Super Lucky. Next year, I will direct an adaptation of Don DeLillo’s novel, White Noise in Germany as well as an opera by Michael Gordon in New York. They are both big, challenging projects. One great thing about this award is that it feels like an opportunity to push myself out of my comfort zones; I’d like to do more of that.

********

Tom Sellar is editor of Theater, a creative journal published by Yale University, and professor at Yale School of Drama. He was a member of the 2017 Herb Alpert Award in Theatre Panel.