Chapter Two

I think you have beautifully described all the things that drew me to make this piece.

Not all my titles initially follow this convention, many are all in lower case etc. Most publications and some institutions will unfortunately (auto)correct the titling once it is several times removed from my studio.

****

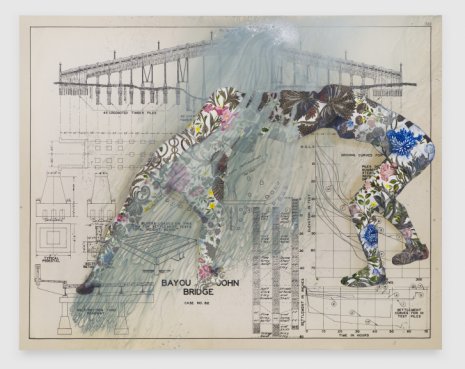

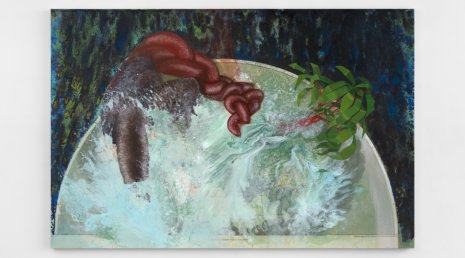

The use of pattern and ornamentation in my work usually references the broad-range symbols of resistance and healing within the black diaspora. For example, azabaches or figas in Brazil, that have a resonance with the Black Power fist. My effort is to say that we’ve had moments of healing and resistance and self-definition hundreds of years before that, and that maybe this is in conversation with both.

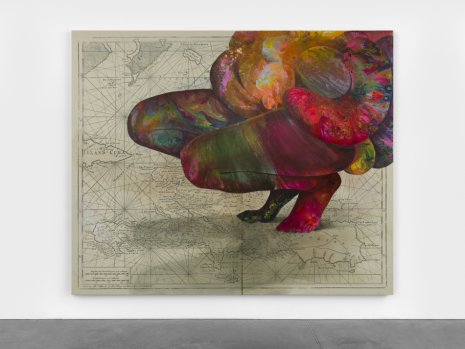

A lot of my work has been about recontextualizing Caribbean history and making more evident how it’s been formative to a lot of ideas around the world. When you think of things like the Enlightenment and modernist ideas of progress, they’ve been formed by the actions of, not just the bodies and the labor of, the Caribbean. Martinique and Haiti in particular have been extremely formative. I wanted to bring that, and to think of the women who were excluded even from those epic narratives.

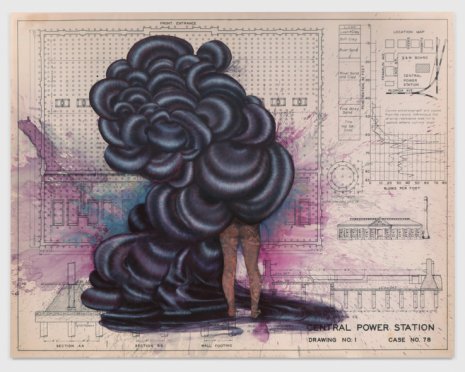

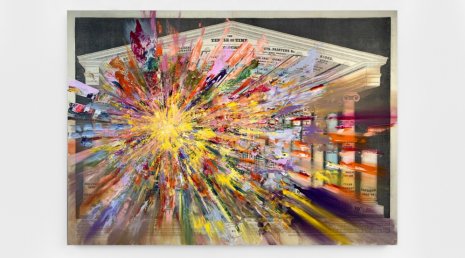

I've been a bibliophile since I was very little—I would always save my money for the book fair at school. As a book hoarder, I was always drawn to writing as a way of escaping, but books also played a role as a window into different spaces. I began collecting books deaccessioned by libraries. Over time I became more aware of why these things were being deaccessioned, and that it wasn't necessarily just a cleaning out of space to make more room in a physical sense. It was also to conceptually, ethically, make room for new ideas, to disavow what was no longer popular or histories proven to be wrong or that would have been exclusionary. When I started making work on those book pages, it was with a full awareness of how these were both physical and conceptual spaces of exclusion, that fought for someone like me to not exist. Painting directly onto these pages was a way of speaking with them, or to them, directly— depicting figures that reveled in that space and actively destroyed it.

The maps I have been engaging with recently through painting all entail macro-narratives about histories of territories, bodies, and migration that are very reductive—they go back all the way to the Punic Wars, to more contemporary naval charts of different banks within the Caribbean Basin, and mercantile routes in France.

My paintings and installations explore the histories of Afro-Latina and Afro-Caribbean women that have been overshadowed by—albeit absolutely foundational to—dominant Western narratives about migration. More specifically, within the scope of Haitian history I have centered on Marie Louise Christophe, the first queen of Haiti, which gained independence from France in 1804. Following the death of her husband King Henri I of Haiti in 1820, and the fall of the Kingdom of Haiti, she was forced into exile, ultimately settling in Pisa. My recent portraits you described serve as testaments to her and her daughters' importance within the larger narrative of the Haitian Revolution. By reclaiming their story from the margins, celebrating their resilience in the face of unrest and migration, and presenting them as symbolic of the rising of a new people and culture in the New World, my goal is to encourage a more complex view of the independence movements that occurred throughout the Americas during this period.

This time has made me pensive. I have been using the time to recover from a relentless decade of successively larger deadlines. Both an exciting and exhausting hamster wheel all at once. On one hand, I am making a strong effort to reach out to people—friends and family—that a frantic work schedule has distanced me from. Even though we are apart physically, I am trying to lean into technology in order to reconnect. Recovering also means committing to self-care practices: meditation, slowing down, coming to terms with not having to be in a production mindset all the time. As a maker, I am reconnecting with my hands in a way that’s not about ‘product’ but about sensory presence in an expanded sense.

So much of my work is about a sensitivity and responsiveness to place. In particular, as a child of migration, my work is about seeking to better understand our present reality and self-perceptions by finding power in the place that I am from. By using this time to reflect—to take an inventory of where I stand in relation to the important people in my life, routines I've taken for granted, and larger narratives unfolding in the world—I can tap into that sense of my own sensory awareness in order to envision new possible stances, new possible spaces for healing and also resistance.