Why Make Theatre?

GL:

I've been wondering about your relationship to historical sources. You've already mentioned Turing and that "Hello Hi There" was inspired by the Foucault/Chomsky debate; in "Magical" you explored the reenactment of historical feminist performance; Democracy in America took inspiration, at least tangentially, from de Tocqueville. Cage is clearly very important to your work too. You're not a director who stages traditional plays from the past, but you clearly have an acute sense of your lineage. Do you self-consciously and deliberately align yourself in a historical continuum? And, if so, is that comforting?

AD:

I'd be happy to place myself in any kind of lineage that could include all those people: Alan Turing, Michel Foucault, Noam Chomsky, Alexis de Tocqueville, Carolee Schneemann, Martha Rosler, Yoko Ono, Valie Export, and John Cage. A pretty good group. But even that list makes clear that there's no one tradition or school or whatever that I could claim - so I take no comfort! Well, it is good to remember that all the artists and thinkers I most admire, without exception, went through big ups and downs in terms of public reaction and institutional support. That's comforting.

You could say that with the algorithm work I'm basically applying some more or less familiar techniques from visual art and music to theater, and the change of medium brings with it all new questions and problems and opportunities. In that sense I'm following the early algorithmic visual artists and stochastic or rule-based composers. But those influences are all mixed in with everything else.

About historical sources: history is really my thing, especially intellectual history. That's what I studied in college, and it's a big, even foundational part of how I work. I'm always looking for the development of ideas: how they change over time, how those changes take root, and become consensual. It's why Foucault is such an important figure for me – I first encountered that kind of genealogical thinking in his writing – and why it's so critical to try to make visible our invisible assumptions, the generally accepted truths, the seemingly obvious definitions, and to keep expanding the range of what's possible to be thought. In a way it's our only hope. But I almost don't like that I work with anything from the past. I think we have to start weaning ourselves off it, like with an addiction. We try to use history to figure out the present, to empower ourselves towards the future. But it's dangerously easy to get entranced by all those images and stories. In the U.S. at the moment we seem to have two main modes: nostalgia and fear of impending doom. And those two modes are actually one mode: retreat.

GL:

I notice that there are no theater artists in that pretty good group. Are there any you’d like to add? And that leads me to a larger question: why do you still work with theater? It sometimes seems to me like such a conceptually backward medium, compared with the others you cite. What does it offer you that other mediums might not?

AD:

Yes, I noticed that there were no theater artists, too! I guess that with other theater artists I don't tend to think of other theater artists as "influences." It's just the field, and my ideas about theater change too fast. I was 18 when I saw a Howard Barker play and went bananas, but now I don't think of him as being a big influence - it didn't last. Or Romeo Castellucci when I was 24, same thing. Or Castorf a bit later. Those are artists who obviously made a big impact, made a strong statement that no one working in theater can ignore but then their work becomes part of what there is, part of the environment.

I tend to think of influences as those artists or thinkers I continue to grapple with, and those tend to be in other fields for some reason. Maybe it's because the theater artists have already figured out how to make their ideas happen within theater (obviously), so there's nothing left to do there, it’s already done, if you know what I mean. With people in other fields, it's all still open, you still have to figure out what their ideas might mean for theater, there's still loads of thinking and doing to do. Maybe.

I think part of the ambivalence is normal; it's normal to struggle with your form. You try to get down to the essence of the thing, how does it work, what's it made of, how can it be different. But it's become far too fashionable for people to hate theater. Trashing theater has become a kind of badge, like saying, “oh, I work in theater but I’m not one of those regular theater types.” Like women who feel really flattered when men tell them they're "not like other women." It's unseemly.

That said, I can't stand theater! Ha! I guess it's partly because theater has this long history, three thousand years, which is all about the imitation of human behavior, and the idea is that human behavior hasn't changed much in three thousand years, that there's a direct line you can trace from the Greeks through Shakespeare to the present day, and that theater connects us to the eternal human spirit etc etc. I mean, really, gag me with a periaktos. And then, of course, all other art forms went through a more or less traumatic break with representation at some point in the 20th century. Theater artists kept trying to make this break, and failing. It didn't stick. So you can kind of get the impression that theater just decided to ignore big chunks of the 20th century, when all those notions of an unchanging human nature and the Kantian transcendent subject, all that got thrown in the poubelle. (Of course I'm speaking way way way too generally. A lot of international work and a lot of U.S. experimental work should most definitely not be lumped in here.)

I also think Stanislavski and his acolytes did a lot of damage. Going for all that motivation stuff, they turned acting into a demonstration of wanting, wanting, wanting. They basically turned the entire art form into an expression of neediness. And neediness is embarrassing, repulsive, even. (Unlike vulnerability, which is beautiful.) Then, too, the actual material of theater isn't totally clear. It's everything. It's life. It's whatever can happen in a room, or out of a room, or anywhere. I don't even accept the simple Peter Brook notion that all you need is one person doing something and another one watching. Maybe you only need the one person watching. And then you wonder, well why should that one watching person just be watching? Before you know it, you've reinvented Fluxus.

In theory theater should be completely open to all possibilities. I like Cage's definition: theater is something that engages both the eye and the ear. As in life, you have to decide how to fill the space and the time, but at the same time, as in life, there are constraints, certain kinds of structural necessities or problems of time, attention, change and development. And maybe the biggest problem: language. The tension between that openness and those constraints continues to be very exciting to work with.

GL:

I wonder whether there's more to be said about neediness and representation, and if perhaps there's a political dimension to it. Many of the artists on your list of influences were deeply political in their practice, either implicitly or explicitly; the traumatic artistic breaks you mention often coincided with political upheavals. I've been thinking recently about artistic experiments from the second half of the 20th century that were deeply political at core - certainly the performance artists you mentioned and the Living Theater, but even Cage, Cunningham, Judson. So many of their experiments and strategies have now entered the mainstream, or are being appropriated or quoted by young theater and performance artists, but often without a sense of political context.

Influences

Isidore Isou (the Elvis of post-dadaism!) and Letterism, Potlatch and the Letterist International

My college library had the entire collection of Potlatch magazine, the journal of the Letterist International, which was founded by Guy Debord and a few others after a bitter split with Isou over whether Charlie Chaplin was all washed up. (Isou was pro-Chaplin.) But, at least at first, it was all based on Isou's ideas: to use words, symbols and letters as a kind of third artistic mode, after the figurative and the abstract. It takes semantics entirely out of the equation. There were 29 issues published from 1954 to 1957. I used to really have the best intentions to do my proper reading for class, but instead would end up sitting in the stacks reading through Potlatch until the library closed. I was thinking a lot about Letterism for the last act of A Piece of Work.

Marinetti and Russolo, Futurism

The Futurist Manifesto blew my mind into bits. I'd grown up inhaling nostalgia without even realizing it, a second-hand nostalgia for the ‘60s -- you know, everything interesting has already happened, now it's Reagan and reaction and consumerism and everything just gets worse worse worse. Futurism was a great corrective, a big slap across my romantic face. Misogynist, fascist, irritating, stupid boys playing with their stupid war toys -- half of it's beyond bullshit, the rest is brilliant and energizing and yowza. I kind of hate them, and kind of love them. I made my final thesis in grad school about them. Nostalgia is the enemy of art! And so is pasta.

Cage

Hardly needs to be said. My research into Cage changed my work, my thinking, my everything. Obviously the use of chance is a major aspect of my work. But Cage also provides the most wonderful model of how to live as an artist. His humor, his collegiality, his pleasure in his work. The creation of a million thousand tools and possibilities for others to explore, always opening to more and better life, the notion of accepting what is - and taking taste and judgment out of the equation, of rejecting self-expression and autobiography. I interviewed his former assistant, Andrew Culver - I still have the tapes somewhere - and he told me that for the last few years before Cage died, they had started working with computer software to automate the chance procedures of his compositions. They're still online; you can run some of them.

Mark Wilson

I grew up with Mark, he and his family are our closest family friends. He's a kind of second father, or uncle, or non-religious godfather. So computer art was absolutely part of my understanding from a very early age. We had several of his pieces around the apartment I grew up in, things he'd given as birthday gifts. I didn't really understand what he was doing until much later, but I remember the sound of the ink plotter running whenever we had dinner at his house, and a couple of years ago of course I realized that what I've started doing in theater is very closely related to what he and his peers were doing in visual art from the 60s and 70s.

A couple of images like the ones in our family apartment:

Laurie Anderson

I want to be her when I grow up. Endlessly adventurous with her work and her life, just an extraordinary musician, poet, inventor, story-teller, investigator of language, technology and communication. Maybe more than anyone, she was/is my idea of what a New York artist should be.

GL:

What does it mean to be re- enacting Dionysus in 69 in 2013? Or creating large-scale dance-theater works with non artists or community groups for reasons that are largely aesthetic rather than political? Perhaps I'm asking, do you think of yourself as a political artist? Or, are you a politically motivated person? Or, do you feel that your reaction against neediness and representation is somehow politically motivated?

AD:

You're asking very good and difficult questions!

On neediness and representation: I think they are linked. I'm speculating, but the question of recognition seems important here. Of course we know recognition as a structural component of classical Greek tragedy, the moment when secrets are revealed, and the characters and audience together "recognize" the truth. "Recognize” means to re-know what was already known before - a bit opposed to the project of expanding the frontiers of knowledge. Rather, it’s about repeating the already known. All representation demands recognition and acknowledgement. It doesn't work if people don't get what is being represented. Probably that's where the neediness comes in. You could say that representation is conservative in its basic functioning. It's an affirmation of what is commonly understood, of what is, rather than a production of new possibilities for what could be.

In a way, this leads us to this current craze for reenactment - all these young artists using old performances. It's a strange phenomenon. Anne [Juren] and I talked about this a lot when we worked with performance art pieces from the 60s/70s in Magical. It's really the subject matter of Magical, this mechanism whereby formerly radical work gets drained of its political content, and is used as pure style or image. What was once urgent and immediate becomes an exercise in recall and recognition. I remember seeing Madonna's 2006 HBO special - she was in her guitar phase - and in one song she was appropriating signs and symbols of punk rock and I thought, this is the end of everything. Little did I know we would soon have Abramovic at MOMA, and Beyoncé plagiarizing Anna Teresa de Keersmaeker, and so on. Luckily some artists like Carolee Schneemann are starting to call us out on this. (The choreographer Mette Ingvartsen wrote to Schneemann asking for permission to re-enact Meat Joy, and Schneemann wrote an open letter in response that was recently published in PAJ. It's worth reading.) On the one hand, I understand it - we're in a generation that absorbed so much visual information, it makes sense that we are still trying to digest it all. But I do worry that our absorption in past images is really just nostalgia, and a kind of abdication in the face of a present we don't know what to make of. We borrow the artistic strategies of previous generations because we haven't developed our own. And, in the borrowing, the politics, the urgency gets neutered.

A friend of mine, the curator Florian Malzacher, made a related point about philosophy and activism in his new book. I'll just quote him because he says it better than I ever could:

"A generation of philosophers that derived their theoretical concepts from their own, concrete political experiences and engagements (for example in the leftist groups in France and Italy of the 1970s) was followed by generations of philosophers (and artists, curators etc.) that built on these thoughts and abstracted them further – but too often without binding them back to their own contemporary reality. So we got used to calling concepts, cultural theories, and art works “political” even if they are only very distantly based on theories that themselves were already abstracted from the concrete political impulses that sparked them. A homeopathic, second hand idea of political philosophy and art has become the main line of contemporary cultural discourse."

As for whether I consider myself political, as artist or citizen...I feel I have to be careful here. I'm clearly not making activist art. I'm not tackling issues with a capital I, or intervening in the public square. But I'm always aware of a political intention guiding my work. It's a kind of project towards empowerment.

For the algorithm projects, this means using quite simple tools, so that the audience has a chance to understand the under-structure, the governing rules, so they can "see through" the interface. This seems vitally important. With these new digital tools, we are in danger of creating a kind of holy order of priests, who understand the technology and are comfortable manipulating it, while the rest of us are the objects of those manipulations. We need to demystify those tools, and get familiar with their implications. That’s one kind of project.

Further, I take from Chomsky the belief in the intellectual capacities of all humans, and the belief that there is great pleasure and freedom to be found in the exercise of those capacities. I'd like to propose a situation in life where we are neither anyone’s master nor anyone's slave. Actually, where we are not anything's master or slave. That includes animals, and it includes objects, concepts, and structures.

Trisha Brown

I loved Trisha Brown long before I really got into dance. I think I saw Group Primary Accumulation with my mother, must have been in revival in the late 80s, no idea where. The Joyce? City Center? It was great there, and it's pretty nice in this video in the park, too. There's such a pleasure in the unfolding of the structure, a kind of embodied mathematical delight.

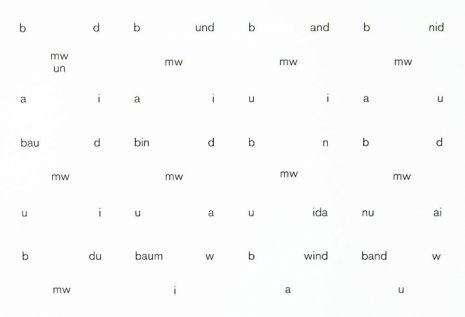

Eugene Gomringer

His use of language as a material has become very important to me - I'm not playing with it visually as much as he did, but rather in terms of theatrical language: the sound of words, and their relationship to intention and character. Trying to break open words as objects, and to keep a tension between the materiality and the content. Gomringer's work (and that of his peers) kind of pointed me in a direction, how to make the double nature of language perceptible.

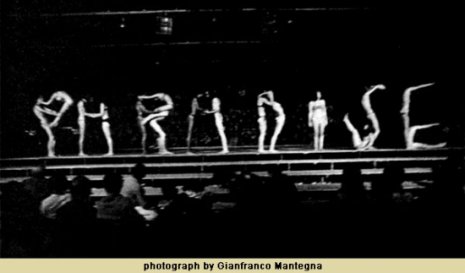

The Living Theater

They are not so much an influence aesthetically (though if you look closely at Passing Strange you can find a reference to Paradise Now, though actually that might have gotten cut in the move uptown...), but more in marking out a standard of ethical and political integrity.

Here's part of a text I wrote about them a few years ago: "It’s nothing but our polite good manners as audiences, our respect of the imaginary borders, our willing compliance with the rules that govern social norms, that keep us quiet and in our seats. The Living Theater offers us the tantalizing possibility: what if? What if we all stopped believing in these illusory boundaries and just…got up?"

I grew up in New York on the upper west side, and in that era, in the late ‘70s, John and Yoko were really like "ours" somehow, at least in our minds. Sean went to school with one of my upstairs neighbors, and my older sisters would sometimes see John around on Columbus Avenue. But the line on Yoko was always that nonsense about the Beatles' breakup and her crazy singing voice. It's amazing to think back to how much people hated her. But then I checked out her work - maybe because of her position in the pop world, she was probably my first encounter with conceptualism. I loved it, the wit, simplicity, and beauty of her pieces. Totally radical, but positive and idealistic rather than brutal or shocking.