In Virginia's Words...

Before the pandemic, I was making theatre in a public plaza in Chinatown, Los Angeles, before that, under a freeway in Tucson, before that, in a prison in Arizona, before that, I was very sick. You need to find your moon, someone once said to me, reminding me that in order to get better, I would have to slow down, go deep, and be willing to stay there for a while.

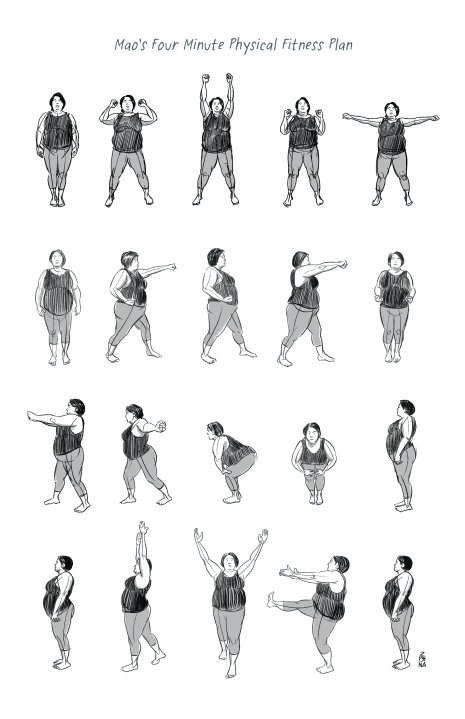

The pandemic initially forced me to revisit the question of practice. As a writer, I returned to something I had neglected or lost sight of, my own physical body. Moving on a daily basis is the only thing I do with consistency right now. Fundamentally, isn’t that what theatre is?

In addition to writing and directing plays, I have created a body of work that is interdisciplinary and includes multimedia performance, dance theatre, performance installations, guerilla theatre, site specific interventions, living room encounters and community gatherings.

I was an organizer before I was an artist. A comrade recently asked me a question that I now think about on the daily—

The question was not metaphor. It was material. How can art get our people out of cages, detention centers, prisons?

The first poem I ever read publicly was in a juvenile detention center in Austin, Texas. This has continued to have an impact on my work. Prisons, both literal and metaphorical, the boxes people try to put us in, and state violence are tropes that recur in my writing. Writing, in part, is my attempt to liberate myself from confinement, conventional rules, and structures, an attempt to imagine freedom.

When I first set out to be an artist, I did everything I could to just keep working, to be a working artist. I am the daughter of a Chinese Mexican immigrant and an airplane mechanic. As someone who grew up in a working-class family, it was important to me that I make a living as an artist. I lived and worked in Los Angeles, Minneapolis and New York. I wrote and directed plays about the Chinese diaspora in Mexico, the Alamo and its legacy of colonization, immigration and the building of the US- Mexico border wall, the execution and lynching of women in South Texas. Transnational migration, colonization, mis-education and state violence are points of theoretical interest in my writing (and yes, things I talk about with people across the kitchen table) but I knew the way I was making work wasn’t going to help me answer the question –

When I was commissioned to adapt Helena María Viramontes’ novel Their Dogs Came with Them for the stage, I advocated for us to turn to our communities as experts, as dramaturges, based on their lived realities and created a playwright-driven page to stage process of development at Perryville Women’s Prison for Their Dogs Came with Them that culminated in its world premiere at the prison’s medium security Santa Cruz Unit in 2019. The play was performed by 17 actors from inside the prison and over 20 collaborating artists from around the country, including four directors (Marc David Pinate, Manny Rivera, Kendra Ware and myself). The cast was Black, Brown, Native, Asian, White. They were queer and straight. Our youngest cast member was in her early 20s, our oldest in her 60s. In addition to over 100 women on the yard, 20 invited outside guests, including college administrators, artistic directors and scholars, attended the performance. An original score was played live by Grammy award-winning artists Martha Gonzalez with Juan Perez, Bob Robles and Tylana Enomoto. In addition, the set designer Tanya Orellana, choreographer Marguerite Hemmings, musical director Martha Gonzalez, and I taught workshops on each of our areas of expertise at the prison, in an attempt to make the process of theatre production transparent and accessible.

I mention this project in detail because it marks a shift in the way I work and is an example of my long-term goals as an artist.

At one of the early workshops, after we had read the novel together, I asked the question—what do you know? This is a question I inherited from Laurie Carlos. One of the women answered with a sense of clarity:

I am desperately trying, as my friend Adela Licona says, to make art as moving matter, art as movement building, by bringing together people, to co-imagine and co-create a world we want to live in, can live in, together. In this model, the play, the theatre, art is a rehearsal for something bigger than ourselves, a gathering of people, across borders and walls we did not make and beyond bars that we are trying to tear down.

As an artist, I want to craft and build spaces for collective dreaming, for ambitious work that is transformative, that demands that we listen to ourselves and to each other, that incites movement. I want to make work that sets people free.

When I won the Yale Award and the Whiting Award, I put aside some of that money to begin making and producing work in San Antonio. It was important to me that I make theatre in the city that raised me even though there was no real infrastructure to do it. But I will. I did. I do. I have - including the time, together with writer Barbara Renaud Gonzalez, I created a piece with over 100 female performers in front of the Alamo where we let out a collective scream against that monument to war and colonization, or the time I took over an empty lot in the city center with visual artist rafa esparza and poet Joe Jimenez (I kept a fire burning in the middle of a hurricane) or the time, with artist Veronica Castillo, we made barbacoa together, cooking the cow’s head in the ground for 14 hours. We invited over 50 artists from 13 states across time and space during COVID to join us in this celebration.

And even though it is not documented, recorded, or published I know it is not only my most ambitious work but my best work. You see, I am trying to make something that is not for “the field” or my career or any award but for my people, as an act of resistance against cultural genocide. I am doing it the only way I know how, with my hands and imagination and a longing for other ways of being in this world, of relating, of being together, outside of capital or capitalism, a desire so damn deep sometimes it hurts.

Sometimes this work cannot be recorded. Like the work we made in the prison. The Department of Corrections refused to let us video the performance. This was a big blow to us especially because I fought hard to premiere the work there.

This is why I started my own production company, a todo dar productions, because I want to make theatre, uncompromising, untranslated and unmediated, in places where theatre doesn't normally exist, for people who look like me and my family and my community, for the queers, the outcasts, the outlaws.

In some ways, I think what is most powerful about my work are the things you don't always get to see like how we create ecologies of care in the face of state violence, how we dream when our communities are under attack, how we create spaces for movement, joy and celebration amidst all of it - to study together and think together, work and collaborate together, imagine and create together.

Since the pandemic, I have decided to stay in Texas and commit to making work in the Southwest, along the I-10 corridor from Houston to Los Angeles, centering autonomy, abolition, and self-determination as art and life practice. I am invested in theatre beyond the black box.