Chapter Two

That’s a good question. I always think I know what I want, but can never bring myself to write an actual “script.” Inventing stories is neither a strength nor a particular interest of mine. But when you work on a team to make a film, the script is like your bible. I tend to talk early and often with my collaborators about how I want a work to feel, or what I hope it will do when it’s done, and we bounce ideas around until we’re more or less on the same page. When other people get involved it sets something into motion, material starts getting generated (research notes, reference images, budgets and schedules) and a script, to whatever extent one is necessary, emerges. But while I might catch glimpses in my mind of how the final piece will be, I never know before I make it, and once I do, my recollection of what I’d imagined is overwritten. Some new thing I couldn’t have predicted exists in the world and does what it does, and I become an audience member, not so different from everyone else.

Sometimes the formal structure of a piece comes first, sometimes it’s the subject, and sometimes they arise in tandem. It’s often a spirit of curiosity that gets things started, or I’ll think of some formal/structural experiment that I can’t get out of my head. For example, years before making H.M. I started wondering what would happen if I ran a single 16mm film through two adjacent projectors, so you’d see two parts of the same film at the same time, side by side, and would eventually see every frame twice. How could I edit a piece like that? And how would watching it feel? I was temporarily obsessed with the notion that space (literally a length of film) had a fixed relation to time (duration) in celluloid, which was no longer the case in digital media.

Psychoanalysis had been a useful lens for thinking about subjectivity and experience, and around 2005 I started getting interested in neuroscience, mainly because I find it unfathomable that all of human consciousness is materialized in the meat between our ears. And then I heard about the case of Patient H.M., who lost his ability to make lasting memories when doctors removed his hippocampus in an effort to cure his epilepsy. Patient H.M. could only remember things for about 20 seconds before they were gone forever. When you watch my double film projection, you know you’re seeing the same thing twice, but because we, like H.M., have about 20 seconds of short-term memory, we too feel, at times, like we’re seeing the repeated image for the very first time.

Critical Mass might be a good example of what you’re talking about. It also exemplifies a third way that form and content develop for me, which is through what I have come to call my “good bad ideas.” These are the projects where the central conceit sounds great when I first think of it (So elegant! So pure!) but once production starts they take me through a very dark place where I have to wonder if the immense amount of effort required to make the piece is, in fact, worth it. Greystone (2012) is the example of a “good bad idea” par excellence.

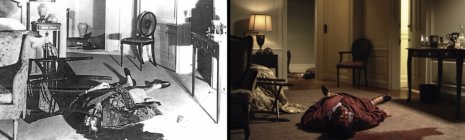

I came up with my idea for Critical Mass (2010–), while watching a theatrical screening of Hollis Frampton’s Critical Mass (1971). His film, which was made by shooting three reels of film straight through, copying them, chopping the copies up into tiny snippets and reassembling them into a two-steps-forward-one-step-back sort of format, follows an explosive argument between a young couple. It was striking that, despite the fact that their image and sound were mostly out of synch, and despite the fact that you could rarely watch for more than a couple of seconds before you’d encounter an edit, and despite the fact that the characters were practically caricatures of New York art students in the 70s, I couldn’t help but empathize with each of them and their story. How is that even possible? I have a hyperactive sense of empathy, for sure, but even at that level of mediation I was moved. Maybe it was the mediation itself that was moving, because as the argument fails to progress, so too does the film, and we experience in a new way the young couples frustration. Maybe it was the fact that the gender dynamics in the piece still sounded familiar 40 years later. Maybe it was that I was a sucker for structuralist film, all the better if its’ subject was social. Regardless, I became obsessed with a question: what would happen if you tried to perform Critical Mass as a live work? Could I even find two performers who would be able to memorize that edited argument, word for word and cut for cut, and do it live without seriously messing up?

It was all of those. Film, photo, and video are the preferred media to document performance, whose ephemerality often keeps it from reaching a wider audience. Here, performance brings an absent film back to life and holds some reflection of it up to a new audience. Some viewers of my Critical Mass have also seen Hollis Frampton’s film. Many haven’t. So while the actors have to rely on a kind of bodily memory (running on automatic at some level, after many months of practice, to effectively perform the piece) they must also respond in real time to each other’s words and actions, experiencing the argument anew, very much in the present. They can’t think too hard about what they are doing or they will lose their rhythm and make a mistake. But they can’t forget what they are doing and just go with the rhythm, or they won’t connect with one another, and no real sparks will fly. The audience, meanwhile, may be recalling the Frampton film, and comparing that absent artifact to the living thing in front of them, which keeps barreling ahead like a freight train. Eventually, they have to kind of relax into the cognitive dissonance and let it flow through them, or else struggle to follow the dialog in its absurdly non-linear presentation.

I started out thinking I should try to “change the world.” I don’t know how often art can do that, and I think there are more practical ways to channel one’s energies into social change if that’s the goal. But I do think that the ethics of representation count, and I hope that the representations I make provide opportunities to think critically about topics that matter, free from the demands of more traditional, instrumentalized or commercialized media.

My understanding of the role my work as an artist might play in all of this has shifted since growing up and having kids and getting involved in local politics. I do a lot of things that are not art that I believe make some measurable difference in the world, and these non‑art experiences—as a teacher, community organizer, activist and parent—have, unexpectedly, unburdened my work of a demand it could never quite satisfy. I also think that politicizing representation—finding new ways of using the moving image to bring us closer to the experiences of others, particularly marginalized others— often does more good than simply representing politics in art. So while I’m hopeful that my work might produce something meaningful in the world, I’m ok with the fact that that “something” can’t necessarily be quantified.

*****

Diana Nawi is Associate Curator at Pérez Art Museum Miami where she has curated Nari Ward: Sun Splashed; Iman Issa: Heritage Studies; and Adler Guerrier: Formulating a Plot among other exhibitions and programs. In 2017 Nawi will organize John Akomfrah: Tropikos, John Dunkley: Neither Day nor Night and newly commissioned project with Haroon Mirza.