Chapter One

This email conversation between Kerry Tribe, in Los Angeles, and Diana Nawi*, in Miami, took place in March and April 2017.

My last year in college I made a piece called FAMILY / MEMORY / ROUGH / CUTS, which started out as an earnest attempt at a home movie about my mother and her senile father and the difficulties of making sense of a past that can’t be agreed upon (if it’s even remembered). What I ended up making, though, was a structural experimental video with hardly any live action. It was mostly just a black screen with white text and sound, intercut with a few snippets of hand held footage featuring my relatives at a family reunion. Watching it, you had to decide if you wanted to pay attention to the titles, which included verifiable facts about my family history and subjective musings about why the video wasn’t working out; or, if you wanted to pay attention to the soundtrack, which included my mother trying to explain her reasons for moving her elderly father out of her house in New England and into a nursing home in Florida. The video was self-reflexive and its modus operandi was essentially cognitive dissonance, which continues to be of interest to me and is front and center in pieces like H.M. (2009) and Critical Mass (2010¬–2015).

I made that video at Brown and in my crit they asked to watch it twice so they could take it all in. People talked about how it felt to watch it, and how that feeling related to the difficult and personal subject matter. I remember one kid asked if he could bring a copy home to show his family over the holidays, which meant a lot to me. This feeling that I could make something that was quite personal and unorthodox in its structure and frankly “difficult” and still connect with an audience—maybe even an audience I’d never meet—this was something I wanted more of.

My parents were politically active progressives, and as I understood it, to grow up and be a successful contributing member of society meant to try to leave the world a better place than you found it. That’s a tall order for an artist! How do you quantify subjective effects? This was, and continues to be, a big question for me. Why make art when you could be doing something much more practical to ameliorate the unfathomable suffering that’s everywhere around us? How is this, in the big scheme of things, important? Nevertheless having the skill set and temperament that I had, I was not about to become an aid worker or brain surgeon, so I think I felt a responsibility to at least make art that might, at minimum, concern itself with subjects of social interest and import.

In 1997 I moved to New York City, where I attended the Whitney Independent Study Program two days a week and worked as a bike messenger three days a week and, subsequently, as Martha Rosler’s assistant. It was a challenging time for me. On the one hand, I felt I’d found my people at the ISP and appreciated our shared sense of urgency around art’s possible relationship to social justice. On the other hand, I spent a lot of time feeling intellectually insecure—never a mindset conducive to creative exploration.

Compared to the physical safety of our reading group, working as a bike messenger might sound scary, but to me it was the opposite. The days I spent crisscrossing Manhattan provided a necessary counterpoint to all the voices in my head. It was an embodied experience that brought me into contact with all kinds of people and places I otherwise wouldn’t have known. I remember dragging my messenger friends to see my final piece for the ISP (The Audition Tapes (1999))—which they made fun of—and feeling really happy to have these different communities colliding in front of my work. I still get excited about working with people who have basically nothing to do with fine art—neuroscientists, entomologists, firefighters, engineers, animal trainers…

At Brown and in the Whitney Program I had nurtured a suspicion of expressivity, beauty, and intuition that I brought with me to Los Angeles. I had little patience for what most people consider fine art: if it wasn’t implicitly political or explicitly conceptual and probably involved video I basically wasn’t interested. I was tone deaf to the myriad ways that art can critically respond to the world, regardless of mode or medium.

I came to LA in 1999 to study with Mary Kelly, who I had met at the Whitney Program, and with Juli Carson, who was a kind of mentor to me. But I probably learned as much from my peers and from professors who I hadn’t realized would have so much to offer, like Paul McCarthy and Chris Williams.

Though regular and intensive crit classes I learned to attend to how it actually feels to be present with a particular work or installation. Lari Pitman would talk about how a work “comports itself” in the presence of its viewer, and of the value of “linguistic delay”—that magic than can happen when a piece thwarts your ability to make sense of it, name it, pin it down. Mary Kelly actually performed linguistic delay in her crits, modulating the unfolding of our conversations to slow down the tendency to jump to what we think things mean, refer to, what the artist’s intentions are and so on. Instead she asked us to begin each crit with an almost Zen sense of bare attention to the affective and phenomenological experiences we were having. Mary could talk about anything, and everything she talked about became interesting, and I started to loosen my thinking about what might make for “good” work.

Both. A work’s subject matter is only ever as compelling as its formal realization. Things that I find boring or totally meaningless can become fascinating through good work, and fantastic subject matter regularly dies in work that has no magic.

I moved to LA at the turn of the 21st century, when reality television was taking over— when digital editing became the norm and anyone could make a video and everyone could attain their 15 minutes of fame. So questions around self-representation and the individual’s relationship to mass entertainment and spectacle continued to feel relevant. While in grad school I made a video called Double (2001) that involved casting professional actors to try and play me. A year later, I hired a small crew for the first time to help shoot Here & Elsewhere (2002). As my work was developing around the corner from Hollywood, I started thinking about how the language of documentary and narrative TV and cinema could be deployed to my own ends. I’m not sure this would have happened had I been living anywhere else.

I think having actors stand in for me and members of my family in those early works did a number of things. In terms of subject matter, my own autobiography felt like fair game at a time when I was reluctant to try to speak on behalf of anyone else; this was a topic on which I was a trusted authority. Working with actors also meant that I didn’t have to picture my actual family, and kept me comfortably on my side of the camera.

On another level, having multiple actors play each “real character” underscored the role of casting, which is all about finding the right person to embody a character with whom the audience can identify. Casting multiple actors for each part also disrupts the suspension of disbelief. Spreading that narrator across multiple performers suggests the fallacy of a unified, coherent subject position.

But I’m still very present in my work, albeit less explicitly. The Aphasia Poetry Club (2015) is, in one sense, a portrait of three people with brain damage. But it’s equally about the difficulty of expression — what one internally knows and feels and wants others to understand. Artists are familiar with this struggle: each project, for me at least, includes periods of intense anxiety and frustration as I try to find the right form, the right way, the right language to represent notions that, until the work is done, are infuriatingly hard to pin down. I talked a lot about this struggle with my aphasic subjects as we tried to find ways to represent them that felt truthful. At one point, one of the narrators says, “I’m aphasic, and you’re an artist, but we have in commonality of trying to express ourself. That’s why…we entrust you to use you through it. Because it’s like two layers deep…It’s not coming the way I want to. But, regardless, it’s the same experience, right?”

I was never any good at drawing or painting and despite my professors’ insistence that neither was essential for success as an artist, I felt and continue to experience this as a liability. But like I said, the videos I was making [as an undergrad] seemed to actually connect with an audience. Editing came naturally to me. It felt like listening to music, where I just kind of knew what was supposed to come next and when. Putting images with sound in time clearly produced specific cognitive, phenomenological, and emotional effects that could be predicted, exploited, or undermined. Is that unique to time-based media? I’m not sure.

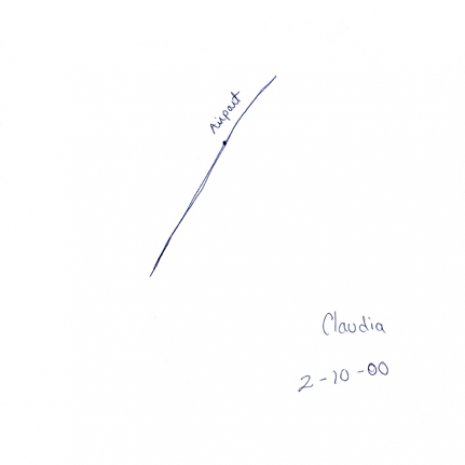

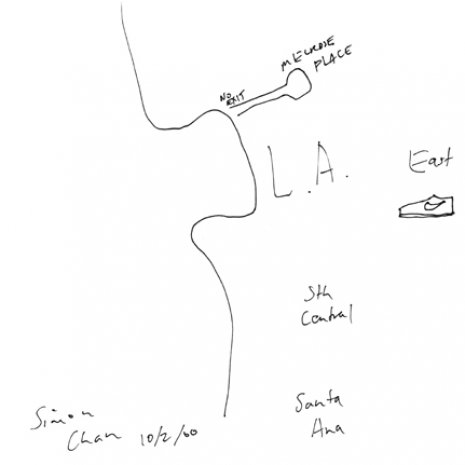

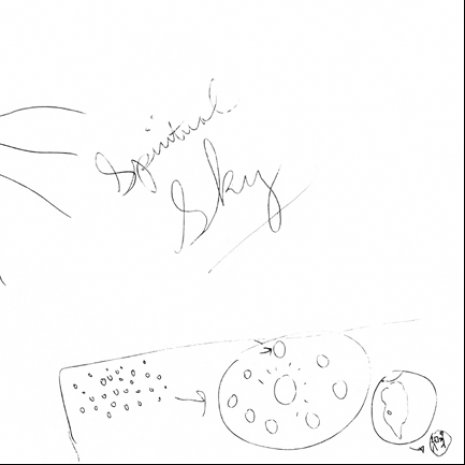

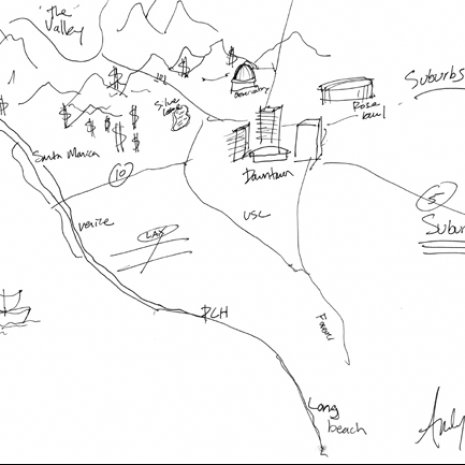

Right. That project—where I approached strangers at LAX and asked them to draw maps of the city—points to another through-line in my work, which has something to do with the relationship between the “official” versions of things and the idiosyncratic realities of lived experience.