In Tania's Words...

My work exists comfortably and uncomfortably between practices of artistic and political nature. It exists within the contradictions of my own life journey. I have studied theater for most of life at the level of BA, Masters, and Doctorate. I toured my work significantly in theater festivals, I taught in theater departments, and won several theater awards. Yet I never created a play to be presented on a stage in a theater for an audience seated in the dark. I have always experimented with audience interactivity often outside institutionalized spaces. Back in Lebanon, when I co-founded Dictaphone Group in 2010, I was guided by a commitment to spatial justice, and was drawn to creating performance work in the contested public space that forced me and my collaborators to question the politics of space through performance: Who is allowed in these spaces? Who feels invited? Who use these spaces regularly? Who passes by? What laws govern them? What are their daily negotiations? Who feels surveilled and controlled here?

In terms of form, my work focuses on the central element of liveness and that is the encounter with the audience. My audience has never felt like a faceless crowd; they are co-creators and collaborators. Sometimes they are the sole performers of the work, transforming it from an installation into a live art performance. In these instances, each encounter with a new audience holds the potential of an entirely new experience. Each audience has the capacity to shift the work slightly, and sometimes drastically. When creating new work, the interaction with an audience does not come last as it is often the case in theater, it is the guiding image of the work. How I choose to encounter the audience ends up dictating the main form of the work, which can vary from site-specific performance, lecture performance, one-on-one performance, interactive sound or video performance, amongst others.

In terms of content, my work has been described as feminist, playful, and politically-driven. For as far as I can remember I have created work that actively resists borders. The internal and external borders, the visible and invisible, borders within our bodies, colonial borders, cities as borders, the art industry as a border, and national borders as a space to make people disappear. As an example, two of my works - As Far As My Fingertips Take Me and Cultural Exchange Rate - confront borders’ effect on people’s bodies and mental states.

I have recently been offered the opportunity to lead a new project that researches and supports the intersection of art and human rights in an academic setting. As part of this job and beyond it, I was also offered the chance to curate other artists work for the first time. I took both these opportunities seriously as I know that artists, especially those coming from a working-class background and/or are BIPOC, are rarely giving a seat at the table in art institutions. I was drawn to the excitement of working collaboratively with other artists to create a program where our works sit side by side and speak to each other. My utmost goal in these roles is to shift the institutions into becoming artist-centric spaces that put people first before their outcome. The desire is that we all practice the very politics we believe in, not only on paper or in the content of our thematic focus but in the most mundane parts of our work processes.

On a personal level and concerning my own creations, I want to focus on areas that have been recently concerning me. Along many of my peers who have spent the last decades touring excessively in order to be able to survive from our artwork and maintain our careers, I am thinking about the sustainability of such practice. In a world coming out of a pandemic and in the midst of climate disaster, how could we work internationally and sustainably at the same time? Site-specific work and long local collaborations can be one way to work. In the center I co-founded, OSUN Center for Human Rights & the Arts at Bard College, in an attempt to decentralize and decolonize financial support and collaboration, we share resources with other artists and curators around the world to create local iterations of our festival on their own terms with no strings attached.

I also aim to attempt to collaborate with extra-human beings. I am currently creating a new work on my relationship to the soil, the one I grew up with and the one I currently reside over. Both hold layers of trauma, ranging from war, toxic garbage, to settler colonial uprooting. The piece, Memory of Birds, invites migrant birds to the scene while exploring migrant people’s survival tactics in planting themselves in new soil and deciding to intentionally forget.

In 2016, I created a work that I once dreamt about. As Far As My Fingertips Take Me is a one-on-one encounter between an audience member and a refugee that came to me as an image in a dream. The audience member and the refugee (performed by artist Basel Zaraa who was born in Yarmouk Refugee Camp in Damascus), encounter each other through a hole in a gallery wall. The artist draws a group of people fleeing on the arm of the audience and shares with them a song through headphones.

I first understood this 10-minute show as one critical of the role of art in producing empathy. It asks, can an audience be literally touched by a refugee story? And can the art world, presented by a sterile gallery wall, facilitate such empathy? The piece was understood by others in ways that I didn’t imagine or “dream.” I have met people who managed to keep the drawing on their arm for two weeks, consequently extending a short performance into a durational piece. I have been contacted by a couple of people who tattooed the drawing on their body, perhaps as a long-lasting sign of their solidarity.

As Far As My Fingertips Take Me was commissioned by Royal Court Theater and Lift Festival in London who wanted to address the “refugee crisis.” It was crucial for both Basel and I to counter the idea that the refugee “crisis” is a new phenomenon rather than an ongoing reality enforced by decades of wars and occupations, capitalist development, xenophobia, and securitized border politics. Hence the telling of his family story that marks decades of life as refugees.

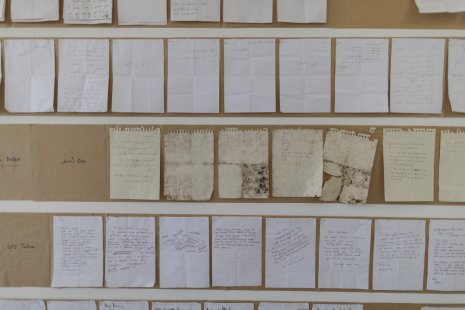

In 2019, I created a performance entitled Cultural Exchange Rate that shares my own family history across a century of time hailing from a deprived border village between Lebanon and Syria and attempting emigration to the Americas. The piece invites the audience to open cabinet boxes and immerse their heads into my family’s personal items, oral histories, and collected archive. In this multi-media and multi-sensory work, the deeply personal - including an x-ray video of my baby still a fetus inside me - meets the cold official state archive and evokes the global quest of the marginalized to attempt a better life.

In order to build this performance, I embarked on research trips both to Mexico City and Akkar (Lebanon). In Mexico City, I met lost family members who have lived there for many generations in order to learn about the start of our family’s migration to Mexico and record oral histories about my great grandparents. In Akkar, I recorded oral histories about my family’s border crossing when fleeing the Lebanese Civil War. The process included a number of collaborations with designers, musicians, historians, and archaeologists.

Although Cultural Exchange Rate functions as a performance, there are no performers in the piece. It features an audience guide and a team of technicians who freely enter the space when needed. It is the audience members themselves who perform the piece. They activate the space and transform an installation into a live event. Ten audience members work around each other, glance at each other, sometimes follow each other, other times wait for each other. Meanwhile, they each create their own journey and experience.

Scale is an important element in the design of the piece. The actual space of the performance is relatively large; so are the cabinets that constitute the set. On the other hand, the audience members experience the work intimately, often only with their faces as when they stick their heads into the various cabinets. It is almost as if the piece is theater for the head—the head here is not merely the brain but the gate that activates all senses. Inside the cabinet, the head is surrounded by a black fabric that shields it from the outside world. On both sides, next to the ears, hidden speakers broadcast sounds, music, or words—so close to the skin that sometimes they can feel the air moving. Close to their eyes they can watch a video or look at pictures or other objects in the cabinets. In one cabinet there are sweets that they can taste. Smell constitutes an element of storytelling in a number of cabinets. The intimacy of these micro-experiences works in juxtaposition with the coldness of bank vaults and the theme of political economy.

Like As Far as My Fingertips Take Me, the chosen form of Cultural Exchange Rate is an opportunity to be self-critical of the role and limits of art in evoking empathy. Do we really need to open one another’s closets and stick our heads in a family’s intimate stories and lives to understand what makes people migrate? I am not sure. Though I now know that being immersed in other realities offers an opportunity not only for the audience to feel empathy but also to evoke their own stories, memories, and feelings on the subject.