In Steffani's Words...

When I was a child, my mother — who grew up in Pittsburgh and visited her family there often — enrolled me in a writing workshop at the Carnegie Museum of Art. Improbably, I remember wandering through the museum alone, writing stories about paintings.

In 2011, my grandfather's obituary in the Chicago Tribune began, "the grandson of a slave," which makes me the granddaughter of the grandson of a slave. I grew up watching him write notes for his weekly sermons on yellow legal pads at the dining room table. Fascinated by language, song, and gesture, and a serious student of Black vernacular rhetoric, he created sublimely moving experiences for weekly sermons, funerals, weddings, prayer meetings, even hospital visits—as powerful as any aesthetic experience mediated by a museum or concert hall.

Today, my creative research uncovers Black vernacular genealogies for cultural practices and technologies like writing, drawing, and performance. I begin with the observation that all paths to drawing do not move through “old masters”—or any masters—and all routes to movement and being moved do not involve European-derived models of “performance.” During the last fifteen years, I have studied alongside artists operating inside and outside the contemporary art industry, including a slam poetry duo, a group of “showtime” acrobats, an R&B trio, a trained pantomime, a pole athlete and gymnast, a team of praise dancers, and a crew of parkour practitioners. My process unfolds across several years and many stages, often beginning with practice-led research and interviews. In dialogue with interlocutors (living and dead), interpreters, and actors, my work connects fields that are rarely in conversation. I look to self-teaching, body-based knowledge, and opaque sites of contact to trace forms of the past into the present and future.

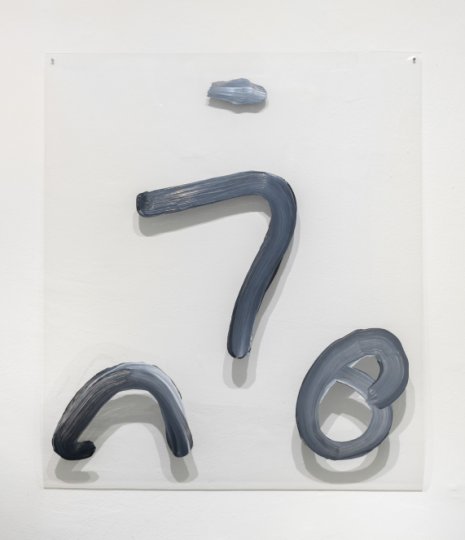

Considering privacy and opacity as political strategies, my recent work focuses on language and its expanded field of gesture. Alongside video and movement, I make drawings and sculptures that materialize my exploration of language, movement, abstraction and opacity, often working with clear materials (translucent barrels, polyester film, glass) as support or container. Many of these works share the title Same Time.

In a movement class not too long ago, a student of the choreographer Steve Paxton reminded me that to become still involves not “stilling”—there is no such thing as “stilling”—but rather applying an equal and opposite reaction. As we were walking forward, the teacher told us to imagine walking backward until we were walking forward and backward at the same speed: in other words, standing.

Recent works in video and sculpture, including In Succession 2019, Toss, Tumbler, and Tumblers ask: when might weight be shared between one body and another? How are power, self-possession, and posse (a Latin root that means “community”) connected? Can a body be a figure and a ground? An end and a means? Simultaneously agent and support?

Guided by my mentors, many of whom find homes for their research inside and outside the academy, I situate my creative and professional practice within an expanded intellectual field. I have made it a specific goal to move freely within a range of contexts, from community spaces to universities to museums. I am currently an Assistant Professor at Rutgers University-New Brunswick, where I work with and learn from a diverse community of students.

Writing plays an important role in my practice. Ten years ago, I founded Future Plan and Program, a small press focusing on literary work by artists of color. In recent years, I have begun to focus my attention on my own writing and the role that writing, as material and process, plays in my practice and research. Last year, I published “Drafts,” a contemplative essay sketching an alternative genealogy for drawing, writing, and abstraction, in Artforum in April 2019. [see top for link to PDF]

I am now finishing my first novel, which loosely grows from my research about mime. In 2020, Quincy Flowers and I co-founded a horizontal platform, at Louis Place, that connects writers across the US and around the world for creative exchange and solidarity.