Chapter Two

………

Text message exchange:

Gosh, I am just struggling to get back to that interview....

I’m sorry to leave you hanging

It’s not a bad question at all. I’m just having difficulty seeing the point in talking about anything right now, certainly about my work.

Maybe a new question would help. I dunno. Everything feels so especially bleak today. Apocalyptic.

………

I don't understand that disconnect at all. Artists and activists are often doing the same thing, even with the same approaches, just in different settings (and sometimes not even in different settings). They are both great, radical problem-solvers. Much of my young adult experience with activism was with Queer Nation, ACT UP, and especially WHAM! (Women's Health Activation and Mobilization), a kind of sister organization to ACT UP in NYC that focused on women's health and reproductive freedom issues. All of those groups were known for direct action tactics. You put your body in the streets and on the line. Your body is the testament and the tool. From the 1960s lunch-counter sit-ins to the 1980s die-ins to the 2010s Black Lives Matter highway shutdowns. In dance, no matter what the overlying message is, the body is the underlying one. Sure, I get a thrill from interesting choreography but the emergency of the body, the absolute singularity of its urgency and languor, what it conveys and carries, is the be-all end-all, really.

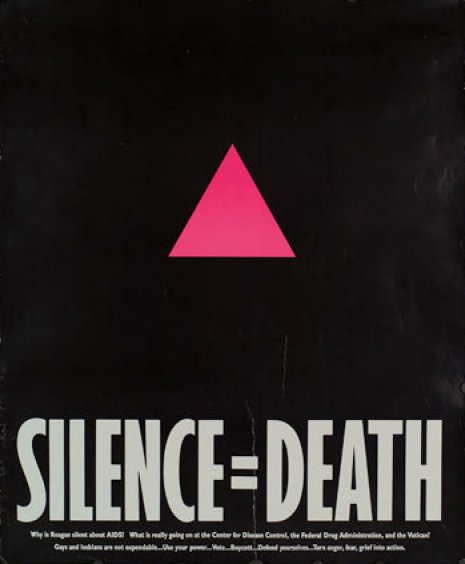

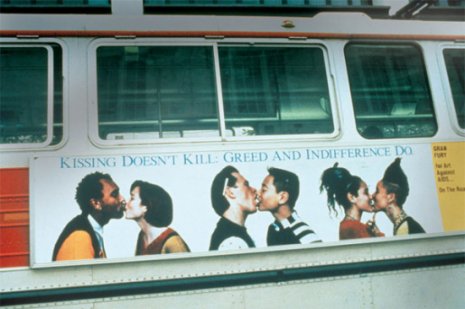

One of the genius outgrowths of ACT UP was the work generated by the Silence = Death project and Gran Fury, the group of designers and artists who made the visual "propaganda”—SILENCE=DEATH; Kissing Doesn't Kill: Greed and Indifference Do; Men Use Condoms or Beat It; Cardinal O'Connor: Public Health Menace.... So many incredible, powerful visual messages that jolted anyone who saw them. It was art, it was activism, it made you be and think and do and feel differently. I remember being profoundly reached by those messages at the time; I stood in admiration of how pithy and effective they were.

Everyone I know is struggling with the prohibition between bodies due to COVID-19. I'm watching many people I knew from AIDS activism leading the way right now, and watching dancemakers try to transform how we reach and support each other while our entire infrastructure dissolves. It seems to me that these groups and these intentions are bound to converge. (Not the least because they both knew healthcare and dance infrastructures were already deeply flawed.)

What is real and who and what to trust are questions for our times, for sure. For the ages. Trust feels extraordinarily heightened right now. The vacuum of leadership at the top contrasted with what we're seeing this week from Andrew Cuomo or Anthony Fauci or Tim Walz. These white men who many of us have protested or argued with or who have made grave mistakes on many other issues are now offering real solace, guidance, and protection (to the degree that's possible). Daddy issues are abounding! Of course, politics are nothing but theater. Even with Cuomo you can see him thinking, "Gonna do an even better 9/11 Giuliani than Giuliani did" and his presidential aspirations may as well be a chyron at the bottom of the screen.

I'm so grateful to dance for how it allows things to be real and surreal at the same time. For those to be the same thing. I noticed a few years ago that people kept using the word "humanity" in relation to my work. This is not a word I would have used or that would even have occurred to me. But apparently that’s what was coming across. When I realized I was hearing that word over and over, and in a way that described not heavy-handed nobility but something more simple and naturally flawed, I found it moving and meaningful. It's not a conscious intention in my work and certainly not an ambition, but its presence is a reflection of what matters to me. In terms of trust...I don't know...that's so personal. I hope you, Arwen, can trust me in my work as I trust you in yours. I hope everyone has someone whose work they trust being inside of. And I hope everyone making work has people within it whom they trust because the process can be so fraught and depleting.

Sheesh. I make those decisions based on things I can't stop thinking about. Things I keep coming back to. It's a cliché at this point but the idea that an artist is making the same piece over and over has some veracity. I often get obsessed with a topic, make a show about it, find myself purged of the obsession by the time the show is done, but its themes often survive and crop up in the next project. The virus mutates, to use a topical metaphor. Loss, human connection, isolation, power—I feel I can never get away from those themes. Fortunately, I have a well-developed sense of humor.

What we're saying here with regard to COVID-19 may be wildly out-of-date or dwarfed by the time this interview goes up. We're living in naïveté and ignorance right now. Trying to stay topical and current in one's work is both a marathon and a sprint. I pay attention to what's happening in the world but speak about it from an internal place. The current external conditions may vary but the core dynamics remain the same. Politically, culturally, sociologically, artistically. I don't believe in "universal experience" but I do believe in individual variations on shared themes. Maybe that's how I address broader issues with abstraction? I'm genuinely curious about other people and ideas in general. I think my work also reads as quite personal—not necessarily autobiographical but emotionally invested. Which I deeply am by nature; with my work, with people, all of it. You can see me in my work. Maybe that goes back to your trust question. Also, like most artists, I don't always know where I'm going to end up. The abstraction comes from the surprises that present themselves in the process and the embodiment comes from following them.

You recently mentioned copperhead, the show I made that was drawn from the experiences of the Manson Family women and Terri Jentz's memoir Strange Piece of Paradise. What intrigued me in those stories was how both victims and perpetrators experienced the violence as a shared encounter linking them together. These crimes were committed at close range, which required touching and feeling each other. The physical/somatic empathy made them worthy subjects for dance. But the stories resonated for me personally, physically. While I drew heavily on images from Paradise and accounts of the Mansons, I also drew on my own experiences in violent encounters. Instead of recreating any of those stories, I focused on the emotional aftermaths and psychological complexities. I created new images to evoke those. There was no enacted violence in the show (except for that one section you referenced earlier where another dancer and I hit each other). But the feeling of violence, power, distrust, and also lush, almost flagrant sensuality hung heavily in the air. Not showing the violence made it creepier, more complicated, harder to reconcile. I'm always careful to say the show wasn't about the Manson Family women or Terri Jentz but was drawn from their experiences. Their stories spoke to me and guided me but it wasn't their stories I was telling. It was a larger story that could have been any of ours. Abstracted but embodied.

I was just reading an article about touch, oxytocin, and mental health, and how this particular pandemic will affect that for our species long term. I wonder how Body Mind Centering® or other somatic modalities could save us right now, lead us out of the darkness and hold us steady for 18 months. Our imaginations are the ultimate virtual reality; could the deprivation of touch we are about to experience for a prolonged period be mitigated by it? I so hope. I agree that this steroidal online world we're in right now can never replace flesh contact. Our memory of touch should be where we turn first in its absence.

I think a lot about the ways we sensorially engage. How we touch through sight or move through others moving or feel parts of ourselves by feeling something outside of ourselves. I don't think about communicating my own experience of making an object but I do think about someone else's physical experience of looking at it or handling it. I suppose they might wonder about my hands-on involvement with the object but I’m thinking about theirs. For the gallery show I had in 2018, Minor Bodies, I considered dancers my primary audience. Largely because they are my main audience and most of my Minneapolis friends are dance folks. But it was also because I think dance people are extraordinarily sophisticated about visual art and they indeed do engage with it from a total, full-body intelligence that is second nature—first nature! One of the pieces, "Ultimate Host," was an upholstered doorway that squeezed you as you went through it. There were challenges to making it in terms of materials—what would give enough pressure against the body without it being impossible to pass through—but I kept thinking, "There are going to be a lot of superfeeler dancers going through there—the bar for sensation is going to be very high!" I wanted the sensations to be mysterious, unfamiliar. I assumed people would try to figure out its construction (I would've) so I experimented with multiple kinds of foam and obscure objects in order to confuse their physical/mental processing. At one point I wanted it to have nodules in places and was stuffing balls into the foam but dancers know their balls! All those hours spent lying on them—they'd immediately be able to identify a softball vs. a lacrosse ball vs. golf ball… They have such a sophisticated sensitivity. Very Princess and the Pea. I gave up on this whole idea because I couldn't find a solution and I kept the materials really simple. Once the show opened I saw that what people really loved—especially the dance folks—was the compression and tactility; the way it touched back. Instead of just passing through the squeezing doorway to get between rooms, people would hang out midway getting hugged by it for minutes at a time. All my concern about foiling their efforts to figure out how I'd made it had been a waste of energy. My desire for them to be somatically mystified was achieved by them being somatically thrilled.

Most of the other objects in that show were wood and I think we're all familiar enough with that material that we can project into our bodies what touching it would feel like. I absolutely love this phenomenon. I think about it all the time when I'm out in the world. How something would feel to touch. Do you do this too? Though it can be excruciating these days, I think that imagining is what will save us.

I miss being in a room with bodies. The project I'm working on now was going to have so much person-to-person touch. My god. Just thinking about it is both a balm and torment. The imagining has to be what saves us.

########