Chapter One

Choreographer Karen Sherman and dancemaker Arwen Wilder’s email conversation took place between March 11 – 25, 2020. Wilder has admired Sherman and her work for nearly 20 years. They live across the park from each other…in Minneapolis.

– Irene Borger, editor and director, Herb Alpert Award in the Arts

I'd danced in one show at that point but as a "non-dancer.” A few months after that, I started working for Movement Research as their Technical Director for the Judson Church series. During tech on one of my first Mondays, one of the artists told me she would walk a series of increasing larger circles in the dark before the sound should start. I was supposed to press play when the circle reached a certain diameter. We teched it successfully but during the show it seemed like her circles weren’t reaching the size she’d indicated and I sat there at the sound board, peering through the murky darkness at her. She kept circling and eventually widened her path to pass right by the sound table at which point she hissed at me accusingly, “Is there a problem??” I was mortified. I biked home that night deeply embarrassed, berating myself for my error. When I got home, there was a message on my answering machine from a choreographer who'd seen me in that dance I'd performed in a few months earlier. She was asking me to dance for her. I considered myself even less of a dancer than a tech director so I called her back and told her I was incapable of dancing in the way she required. That I wasn’t even a dancer at all. She asked how I felt when I watched dance—did my body twitch in its seat? I realized that it did. She said that was my body’s way of telling me it wanted to do what it was seeing, that it could do what it was seeing. That sounded extremely convincing but I still thought she was a fool for asking. I agreed to one rehearsal with the condition that she could fire me afterwards. (She didn’t.)

It always seemed significant that these two things happened on the same night. A real creation myth moment, as if the universe was forcing me to watch dance more closely from the inside and out. And letting me know how simultaneously agonizing and glorious a life in dance was going to be. That twitching-in-your-seat question immediately tuned me to dance as a performer—and it impacted how I worked as a technician, too. Being hissed at by that performer at Judson instantly taught me how to watch dance more closely—to watch the mind of the dancer as closely as the dance, and to watch it with my own body.

I learned a lot reading this question. The words attention and duration are so much more appealing than time. I've been trying in recent years to articulate my thoughts and approach to time—what distinguishes mine from someone else's, if indeed there is any distinction (after all, every dancemaker addresses time)—and I'm still not sure I can. I shape it instinctively in the moment and have been surprised by how much I prioritize it, even though in the moment I wouldn't say I'm consciously thinking about Time. I would probably say I'm thinking about Feeling. And I'm expressing Feeling through Time. Which I guess is Attention and Duration. When we premiered Soft Goods, one friend said I'd made a play in which dance is a character and another said I'd made a dance about time. The more I thought about it the more I realized how true it was. I'm not sure where this sensibility comes from. At one point it occurred to me that maybe because I never went to school for dance or because I didn’t make pretty dance that everything about my dances—including the way I used time—was improper, ad hoc and compositionally distasteful, a clumsy affront. Whether that’s true or not, it ended up becoming a kind of freedom. I've felt like an outsider most of my life, including within dance, but ultimately that's allowed me to disregard a lot of expectations and conventions. I was never going to meet those expectations—I can’t dance pretty—so why try to pass?

Sinister, dread...I know what you mean by that. There’s a disconcerting undercurrent throughout most of my work even when it's funny and wry. Duration is an agent to bubble those things up. As a performer in my own and others' shows, when I’ve had control over how long something could last I would go until I thought it was time to move on and then I’d hang out there just a little longer. At some point I realized this was bringing the room to attention in a certain way because the expected shift was delayed, so maybe this is how I started to develop my own think/feel sense of Time/Feeling. I don't like things to drag on but I really love when they’re allowed to take the time they take, or maybe take a tad longer so it feels a tiny bit weird, suspenseful in a mundane way, a thing flips from funny to disturbing. I know the right amount of time when it arrives. I guess I think more about Timing than Time. I think less about what has elapsed and more about what has just arrived.

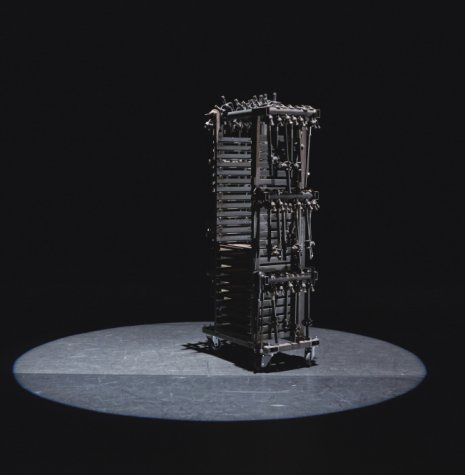

Static things, like the visual artwork I've been doing or the use of objects and machinery in my shows, opens up all this for me in such a new way. The dumbness of objects, their I'm-here-for-the-looking-at nature invites a new challenge to a dance-based approach to time. At least for me. I think Soft Goods did this well but it was hard to mess that up because the objects in that show (Genie lifts, cumbersome stage cable, curtains, treacherous equipment racks) were practically pornographic and exhibitionist. Their strength was in their big, hulking muteness, their physical unfriendliness. Their weight. How they groaned. How much it took for them to change or move. They were geologic. Talk about time....

Well, I do love bodies a whole lot and I don't choose objects all the time. But I've sometimes set out to have a show that was conveniently light on its feet and, by the time I was done, discovered I'd done the opposite. I think I've always been curious about objects but only realized that recently. I walked to school as a kid and would often arrive late because I'd been looking for rusty things in the gutter. I remember one time being in the woods in our neighborhood and finding a glass ring—like a shower curtain ring but solid glass and maybe 1/2" thick. Pulling it out of the dirt was like rescuing a baby bird. Its beauty, the weight of it in my hands, made my body soar. I treasured it and kept it by my bed at night. At some point it broke in half. I was heartbroken. But also fascinated by being able to see the inside of the glass where it had sheared off—the coronal plane I guess we'd call it—but the object itself never felt the same to me after that.

I like objects and scenography sometimes for their aesthetics, often for their mechanics but usually for this heart feeling. (I love trying to figure out how things are put together and this dissembling is not unlike the assembling of a dance; dances are simply the sum of their parts—it’s the putting-together and sequencing that makes a dance whole.) In my dances, objects and sets are really there to serve the dance in their own voice. To reflect the things the dance is doing via another medium. In Soft Goods, the Genie lift's lumbering, groaning, slow precariousness was so incredibly physical. A perfect symbol of the laborious reality of dance. And in production, technicians handle objects all day long. They define you, are an extension of you, so they had to figure prominently in the show because the handling of gear and equipment are modes of creative expression for stage technicians. But the sculpture or object-making I've been doing discreet from dancemaking—though never truly separate from dancemaking— somehow exists in another category that nevertheless encompasses these same desires to feel something; to be in a shared space with something that feels emotionally, intellectually, physically, spiritually, socially worth being next to. Everything I do or make is born from being steeped in dance, from being inculcated with its unity of body, brain, touch, emotion.

We're having this exchange as the coronavirus is beginning to rage through the U.S. Just in the last few days, schools, theaters, businesses have been closing across the country. There is a lot of panic setting in on a national scale now. Store shelves are suddenly empty of certain items and as you peruse the aisles you can practically see the deliberations of the shoppers who came before you hanging in the air: These wipes don't have alcohol. Pass. My parents both worked in medicine, primarily in hospital laboratories. Because of that, I have this sense of on one hand controlling my environment but on the other hand being clear-eyed that avoiding risk is impossible. I've long thought about how the things I touch have been touched by someone else before—a karaoke microphone or a doorknob—and maybe I don't want to lick my hand afterwards but you know, you take your precautions and that's all you can do. But it's so heightened now. Things we bring into our homes that we don't consider to be objects in the sense of works of art or items of use—these cans and bags and containers that are the skins for the contents inside—are suddenly potentially threatening, their physical presence at once alarmingly huge. This is beyond the intent of your question, I know, but currently overshadows it.