Process

PdO:

You are primarily an artist working in cinema, but even when you work outside of that framework, this notion of immateriality permeates the projects you make out in the world even when they are physical and tangible objects: like building an Aeolian harp in the Mojave desert or putting a mirror on a mountain in the Yukon or floating an audio sculpture in the shape of a pentagonal platform in the Washington Channel. I was wondering where a project begins for you? When you begin a thread of research and start to investigate an idea, do you know the final outcome is going to be a film or a site-specific project or something else entirely?

DS:

I generally know right from the get-go whether the idea is going to be a film or not. But I can’t explain why, beyond saying it’s just an intuitive sense of what concepts are best expressed as cinema and which as objects. Research is something I enjoy doing no matter what final form a project takes, though every now and then I make projects that are entirely research-free. They’re kind of palate cleansers. I don’t get entangled in themes. I just touch down, make the piece, and leave.

Sometimes I start researching in the service of a concept or form that’s already in my head. Other times, it’s the research that helps me (or us, in the case of the collaborations I do with my partner Steve Badgett), arrive at a form. Site is always critical. I like when the work and the site achieve a back and forth, a kind of conceptual vibration or volley, so that the work influences the location and vice versa. I like pieces that get a viewer to think more probingly about site. What’s the history of the place? What are its contextual circumstances? What constitutes its economies? What are the infrastructures that allow, or prevent, function? Who controls those infrastructures?

PdO:

Considerations of site are of course inextricably linked to your films as well as your object-based work. How do you work with this idea of the back and forth between site and work when constructing a film?

DS:

This is a hard question because site is absolutely entangled in the work, but so idiosyncratically to each film that I’d need to respond to each on it’s own terms. Some films take huge geographic license, allowing places to be surrogates for whatever location the film makes us believe in. Other films are absolute in their allegiance to physical place. The pilgrimages I make to shoot on-site, to witness a landscape which absorbed an event, is at the root what gives the image its meaning and political context. Some films mix both strategies. And some consider site on an entirely different register. Like the site of a book, or an already existing film, or an emotional site. I choose to shoot some films knowing virtually nothing about the site. And I’ve spent years pondering others.

PdO:

Speaking directly to your cinema work, you work fluidly between film and video. I know you not only shoot 16mm film, but also edit your films on a flatbed, rather than the more convenient mode of digitizing your films and editing on a computer. Even with the still somewhat strong showing of artists working in 16mm film, not many still cut their films on a Steenbeck! What determines your choices to work in video or digital technologies versus shooting and editing a 16mm film in the "traditional" way?

DS:

Slowness. I’m pro slowness - not as the only way to make things, but as one way. Sometimes I like thinking slowly, especially if the ideas that constitute the film are hard. I like that the whole flatbed process is cumbersome. There’s a different kind of editing which happens when you can’t be fleet. Of course it can be maddening at times, when you know exactly what you want and it takes so long to execute. But other times, I really love the rhythms and timing that results from working at such an anachronistic pace. We all know technology is shifting, and sooner or later I won’t be able to cut on film any more. Which is fine. I’m already cutting and constructing things digitally a lot of the time anyways. But I’ll miss having the option to choose which speed of tool is right for the job.

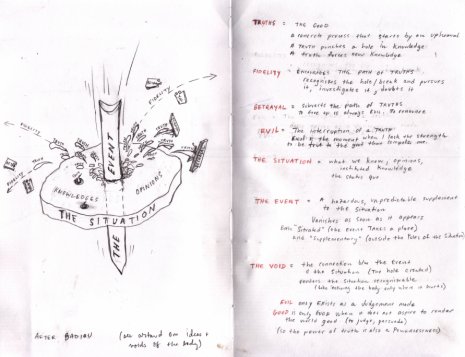

Deborah, afterthought: This conversation has reminded me of a drawing I did for my students (and myself), after we read Alain Badiou's essay on ethics and evil.