Political Embodiment

PdO:

I wonder if you could talk some more about political embodiment in relationship to perception.

DS:

I think of embodiment more broadly than just via our human bodies. For me it might also be a structural body. An embodiment of control could be a prison tower or a master planned community or a jersey barricade or a guard or a television network or the frame around a film image. Embodied resistance I tend to associate more with human bodies. The one who speaks. Those who assemble. The one who takes an alternate path. Though embodied resistance might also be, say, the sandbag that’s holding back the runaway river.

An important ingredient of political embodiment for me is the act of listening. A piece that illustrates this well is Duane Linklater’s It’s Hard to Get…, which is a formally spare film about many things – translation, empathy, colonization, cultural distance, embodiment, melody, repetition, history – but also, ultimately, about listening. If being heard is a fundamental necessity for having political agency, then listening has to be the other half of the arrangement.

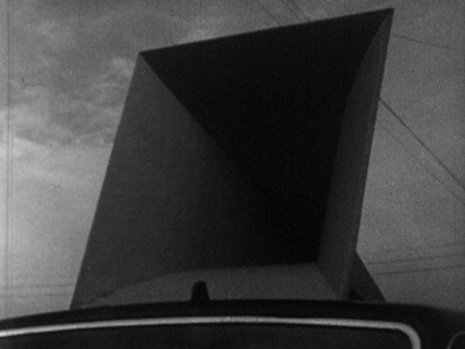

I feel like considering politics, perception and embodiment is something you’re very adroit at yourself. The shows you put together for “History is What’s Happening” is a case in point. They were films about how we choose to move and behave as political beings when we are physically amidst others, or films that were questioning the efficacy of interfaces that offer a different sort of ‘together’ – radio, internet, or that ubiquitous shiny black rectangular i-portal. I thought programming Queen Mother Moore’s speech at Greenhaven prison was a perfect catalyst for exactly this subject.

PdO:

Oh I love that you are citing Duane's film! He's the best.

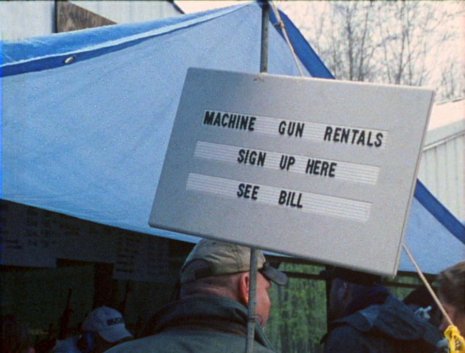

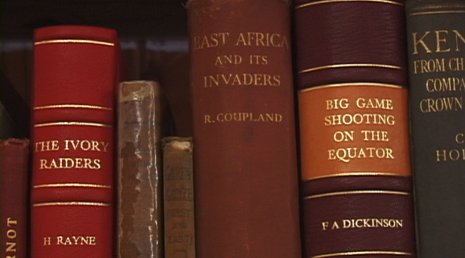

I want to pick up on this idea about listening and hearing here - "If being heard is a fundamental necessity for having political agency, then listening has to be the other half of the arrangement" - specifically in relationship to how you work with the human subjects in your films. No matter if they are incendiary figures (such as the war re-enactors or gun owners in "O'er the Land") or more benign ones (the keeper of the birds of prey in Ray's Birds), you always strike me as being particularly adept at negotiating relationships and working with the subjects in your film. Do you think about the people you film as being active participants in your work?

DS:

I suppose so, yes. In the sense that in order to have a conversation, or a good one at any rate, both people need to be active - actively listening and actively responding. Social negotiations are always interesting to me. They’re a bit of an art form in themselves. Introducing a camera or an audio recorder makes the power balance more fraught, of course. But I enjoy seeing how people integrate the knowledge that they’re being recorded into their verbal responses and body language. Subjects are also active participants in the sense that they constantly causing me to reconsider my framing or question my approach. Some of my films are extremely conversational in this regard. There’s an unstudied, dynamic relationship between who or what will ultimately lead the viewer’s attention. Sometimes the ball is entirely in the subject’s court – vis à vis the story they’re telling, or the attitude they project – and other times it’s in mine.

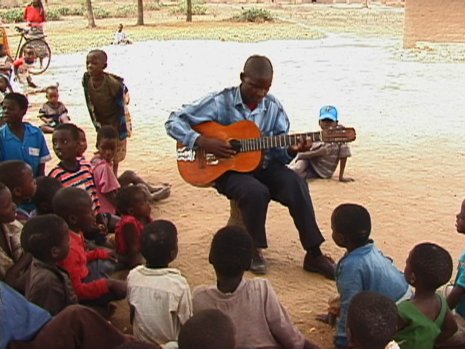

There’s a scene in Kuyenda N’kubvina, which I made in Malawi, where this guy, Agorosso, is telling a great story about how when he was growing up, his village had all these songs they would sing to tease and appease the hippos. He’s completely engaging, and your attention is entirely with him and his songs and his storytelling. Then his cell phone rings and he abruptly exits storytelling mode. He talks to the person on the other end, while the camera stays on. He finishes the conversation and then resumes his story and his singing. During that interim, and probably a bit after, the viewers’ attention is with me, and with the framing of the scene – considering what happens when someone abruptly shifts from public to private, from performing to chatting, but also considering the intersection of culture and technology, and the gap between resident (Agorosso) and guest (me).

PdO:

Where do you see yourself, as a filmmaker or artist, in this idea embodied resistance?

DS:

I’m actually not the best listener. I often lack the patience, and memory of what’s just been said. My problem might be over-engagement. People say things that spin me off immediately into yet another question I want to ask. I have a bad habit of stepping on people’s answers before they’re finished. In part, this is because there’s a very good chance I’ll forget the question if I don’t ask it immediately. This is extremely annoying, both to the speaker, and to me later when I’m trying to edit, and I hear myself yammering over somebody.

Not knowing is a primary catalyst for almost all of my work. It prompts curiosity, or a resistance to ignorance that becomes embodied in the art. I make as a way to get to know things. Which is not to say that being in a place of unknowing isn’t useful. Like I mentioned before, I think it is totally necessary. It’s the unknowing that gets me to question and make art in the first place. Embodied resistance lies in being curious and asking good questions - not in answering them. I think we embody resistance to the status quo when we simply pay attention to what is happening at the present moment, and try to see what it is, rather than what it was, or what we expect it to be.

PdO:

You certainly don't come across as a bad listener! I think this is in large part due to a certain generosity that comes through embracing the position of not knowing. This idea of embodying resistance simply through paying attention is so apropos to how you work. It really speaks to films like "In Order Not To Be Here" or "O'er the Land", which I think can easily be oversimplified as, you say above, what we expect them to be. Once you shoot a film, once you've seen the images and heard the sounds that will compose the final work, how do you carry this sensibility about trying to pay attention to what is happening through to the end?

DS:

By any means possible. Some pieces bear longer attention-paying better than others. Sometimes it’s only out of an extreme force of will. On a nuts and bolts level, paying attention means thinking about what neighboring scenes do to one another. Thinking about rhythm. Thinking about the big picture shape of the film. About how it will begin, how it will end, where the gaps are, where it’s too crowded.

PdO:

I wanted you to talk about re-enactment in your work. There's some obvious examples of it your work, most recently in the staging with the Foley artists in Hacked Circuit. But I was thinking about the term not just in the direct performative sense, but also in the way in which you can use editing and appropriation as a re-enactment, like in "Village, silenced".

DS:

I’m interested in the way that re-enactment ritualizes history. It’s an embodied memorializing. I wonder if it might be our deepest way to remember. I was at humanities round table a few years ago where science writer Margaret Wertheim, citing a working group she’d been part of, brought up the conundrum of signage for radioactive waste storage. What kind of signs will effectively serve as a warning for extremely hazardous material that could be around for a million years – so much longer than any single language has even been in existence? She said every kind of sign they came up with had problems. If you take the ominous route, skull and crossbones, for example, there will always be people attracted to danger, or who believe it’s a false front to hide something of value. They talked about leaving the site unmarked, so as not to draw attention to itself, so it becomes forgotten. And most interesting to me, they talked about how it might be possible to ritualize the site.

In Village, silenced the memory that gets refreshed is multiple. We’re asked to reconsider and remember not just the mining community of Lidice, and the miners of Cwmgiedd who collectively re-enacted Lidice’s annihilation, but also the artist who facilitated the re-enactment (Humphrey Jennings), and the film he made (The Silent Village). Interestingly, both Village, silenced and Hacked Circuit utilize the loop. With Hacked Circuit, I’m thinking about the loop as an essentially paranoid form. But both films, in part through the use of rhyming and looping, point to manifestations of social control and the manipulation of environments.