Chapter One

Interview with Robert O’Hara edited from an email exchange with Todd London, March 13-26, 2018.

It's always difficult to answer the question of the first play you wrote. There are so many phases of development for playwrights from the moment one decides I am a playwright. When you are young everything tells you that writing is a hobby, not something you will grow up to do.

The first play that I remember writing--I was nine or ten--was something for my cousins in the backyard of my grandparents' house, something silly about lost love. I know it had a song in the middle of it, probably a Michael Jackson song, like “She’s Out of My Life” or “The Girl Is Mine.” The first full play I wrote and had done was an adaptation of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, only my version was called Ebony and the Seven Cool Cats. I wrote it as my sixth grade play, and the entire sixth grade class was in it. It also had a famous song in it, “Mirror Mirror,” by Diana Ross. So it should have been clear very early that I was both a budding homosexual and a thief of musicality.

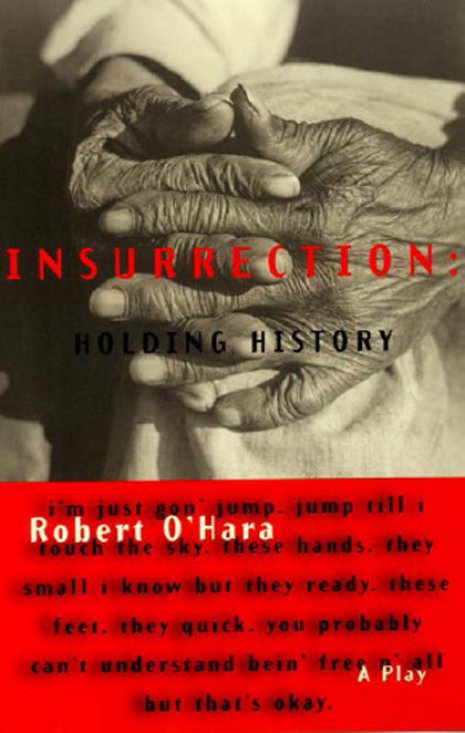

My first professional play to be produced was Insurrection: Holding History, which is about a homosexual grad student at Columbia University going back in time and falling in love with a slave. Written when I was a grad student at Columbia University....

Writing allows me to sit inside my truth and create a fuller truth. It allows me solitude. I am able to live by a motto of mine: “I Will Not Be Limited by Your Imagination.” I mean that for both the viewer/reader of my work but also for myself. It sounds odd to say that I’m not going to let even my own imagination limit me, but it's true. I often tell playwrights not to imagine what should come next, but rather to imagine what should NOT come next--allowing themselves to push the imagination in new ways and not be limited by how it usually functions. That's what writing gives and allows: a challenge to my imagination unfiltered by the realities of the truth.

The truth says that only one play by a writer of color will be produced at most theaters per season, and it will probably be by August Wilson or Lorraine Hansberry. The truth is that my work is still considered by some to be too outrageous (code for Too Black and/or Too Gay) for most stages. The truth is that many theaters are still afraid of both the Black Voice and the Black Body, unless they are presented in a non-threatening manner. Writing allows me to neglect those truths and simply live inside of wonder.

Directing demands that one constantly deal with the logistical truth of what can be done and afforded within a certain length of time. So with directing my relationship to the truth is extraordinarily different than with writing. As a director I push that logistical truth as far into the imagination as possible. Some Artistic Directors don’t see me as a Playwright and Director. They see me as a Black Playwright and Black Director, to call on only if there is a Black project or a "diversity" slot to fill. White playwrights and directors can and are invited to write and direct any and everything, including and especially, stories by artists of color.

I would not be the artist I am without having met and worked with George C. Wolfe. I first encountered his work in college. It was indeed The Colored Museum I read. It hit me like a bolt of lighting. I knew I had found a kindred spirit. I essentially co-founded a Black Theater Company on my predominately white campus so that I could produce The Colored Museum.

My experience with George was full of “tough love.” There was no coddling or hand holding in his mentorship. Rather, there was trial by fire. He was preparing me for the REAL WORLD. When I finished my graduate studies in directing the transition to the professional world was seamless because of the bumps and bruises I’d gotten being George’s assistant director. He also gave me my first artistic residency and produced my first professional play.

George is a genius of satire. His mind goes a million miles a second. I would follow him and just write down random quotes of his, which I still have to this day. As a writer, his use of short pungent scenes and playlets taught me how to, as James Brown says, “hit it and quit it.” His brilliant directorial use of heightened theatricality taught me how to think in an iconic, transformative way about space. George’s shows are full of intelligence, wit and technical profundity. Essentially he taught me how to make an “Event” out of each production.

Also, George deals with the duality of Blackness, its beauty and its horror. He doesn’t believe in the Magical Negro, and neither do I. Oppressed people can be as diabolical as the next person. The American fear of Blackness makes it more and more difficult for us to honestly represent ALL hues of the Black experience, which by its very nature is the American experience. This is why some critics panned Barbecue, accusing me of stereotyping poor blacks performing stereotypical actions. In fact what they call stereotypes, I call my Aunts and Uncles. What they think of as poor, because of speech patterns and clothing, I see as working class, the family and community from which I come and into which much of America returns for Thanksgiving and Xmas.

Many theaters would rather not have Black folks on stage if their representations make white audiences uncomfortable or force them to deal with their Whiteness. But if Black bodies Sing and Dance or, more recently, Rap, they are accepted with open arms, even without a narrative. Black Musical Revues populate our stages in abundance, but we lack original Black narrative musicals, because the Black Body and Black voice are many times not valued, except to talk about how hard it is to be black.

I absolutely, wholeheartedly think of myself as a satirist. It would be hard for me to think otherwise, being a gay black kid raised in Cincinnati, Ohio in the 1970’s and '80’s, with a young working mother, a grandmother who cussed and drank like a sailor, and a grandfather who sent me down to the local bar to pick up his pack of unfiltered Camel cigarettes from the age of seven. I was the kid who won dance contests by imitating Michael Jackson, doing “Rock with You,” who sang and danced in the backyard with his cousins to songs he made up, whose Mom and Granny called his genitalia “bootycandy,” whose teenage uncles called him "faggot" to his face starting at the age three, who wet the bed until high school, who teachers called gifted and put him into advanced classes and whose grad school professor--at an Ivy League school that sits in Harlem--told him he was a little too focused on “African-American and Homosexual issues.” How could I NOT be a satirist?

We are currently living in an American Satire--literally! I wake up and turn on the news, and there in full-blown HD is a Satire.

All around me: We still elect presidents not by the majority rules but by some draconian electoral college that a bunch of privileged white men created while writing “land of the free” and “all men are created equal,” while raping black children as their black parents picked cotton and served mint juleps in a big house. Our nation was born in Satire, and we will destroy ourselves with Satire. I am a product of America in its most primal form. My motto is: “Everybody is Welcome, Nobody is Safe.”