Institutional Weight

GV:

I want to segue for a moment onto a parallel project, one that you initiated a few years before, which is called If only you could see what I have seen with your eyes (an event for acoustic disobedience), 1998, but which I believe is an ongoing project. These are portraits of young incarcerated individuals that deal with your notion of “disappearance,” whether social, political or existential, in a straightforward but very generous way. Can you tell me how this project developed and how it has informed your subsequent work?

DJM:

I think you are referring to two different projects that had overlapping concerns. An event for acoustic disobedience was a national multi-year project that was focused on what is termed “at risk youth.” These are children under the age of 18 who have been incarcerated for an alleged severe crime, but who cannot be prosecuted due to being underage. In every major city across the country these young people are held in what are called ‘lock down units,’ a type of prison for youths who are caught in this in-between space of age, court system, police bias coupled with overt racism, lack of proper education, health care, and being trapped in a lower economic social condition. Most of these kids are black and Latino. I would travel from prison to prison offering to trade my services of teaching art classes and reading seminars in exchange for being allowed to make classical portraits of these young people. Generally they must wear prison uniforms and I asked if they could be photographed in their chosen street clothes. In many cases this was the first formal and desirable photo that had ever been taken of them.

The other project came from teaching in an adult prison in California. Then it occurred to me to extend this idea to prisoners on death row. I began with the prison where Mumia Abdul Jamal was being held in Philadelphia. He was the former Black Panther who was convicted for the 1981 murder of Philadelphia police officer Daniel Faulkner. But not being able to gain access I asked the prison officials and inmates if I could start a project whereby I would exchange essays and books with the prisoners to be followed by a drawing assignment. I called the project Free to the People, 1997, which was inspired by Andrew Carnegie’s words carved over doors of the public library system that he created in Pittsburgh. For two years, I embarked upon a letter-writing project with 164 prisoners on death row. At the end of a two-year period I asked each person to take what they had learned and to draw self-portraits and send them to me so I could make an exhibition out of them. The drawings were nothing short of extraordinary. Not only were their drawing abilities and solutions surprising, so were the insights of these men waiting to die on death row. This informed their drawings with such an honesty and political urgency.

These projects were very much informed by earlier works in the late 1980s and early 1990s where the breadth and scope of the projects went well beyond the traditional white box as a form of exhibition. For example, in Seattle in 1991, there was, IN PUBLIC a citywide, site-generated public art project. In 1993, I worked with Mary Jane Jacobs in Chicago on a public art project called Culture in Action. At Cornell University, Chon Noriega included me in a group exhibition called “Revelation/Revelaciones: Hispanic Art of Evanescence,” where I proposed a site-specific work titled, The Castle is Burning, 1993. The piece was inspired by two events that occurred at the university in 1969. One was Willoughby Sharpe’s historic Earth Art exhibition that presented the emerging earthworks art movement in a U.S. museum for the first time. The other incident was the 36-hour takeover of Willard Straight Hall by the Afro-American Society on April 18, 1969, after a burning cross was discovered outside the black women students’ cooperative called the Wari House. Twenty-four years later, my piece ended up sparking a similar protest after racial slurs and political comments were spray-painted onto the work and other parts of it destroyed. The five-year project of Deep River Gallery in Los Angeles was an artist-generated intervention into the idea of galleries and display in downtown Los Angeles that was founded by Rolo Castillo, Glenn Kaino, Tracey Shiffman, and me.

All these projects, and many others, had many of the same concerns of being durational interrogations and critiques of institutional spaces. They created a form of speculative ethical and ideological platforms that were pushed into the forefront of the sociopolitical landscape. These were nothing less than acts of poetic terrorism. It seemed perfectly clear that the stakes were so high and the social concerns so urgent that this required the most potent means of bearing witness and focusing a spotlight on what was being left, either in the shadows and/or dismissed, forgotten subjects and topics that were actually crucial to our examination of power. Perhaps my concerns were informed by the idea of our future and destiny as a species and how that destiny appears to be seemingly random.

GV:

I’m jumping now into a project titled, The House America Built, 2004, which explores a different type of social conditioning and a man named Theodore Kaczynski. Here you focus on social anarchy and consumer culture as an extreme example of social aberration.

DJM:

Kaczynski is an excellent example of social and behavioral modification resulting in the next evolution of radical violent revolutionary action. But let me back up for a moment. I have many different intersecting interests in Kaczynski as he was a very complex and interesting person. One focus was his cabin in Montana where he lived. After his arrest his cabin was moved on a truck to the courthouse in order to show it to the jury as forensic evidence of his extremism and insanity. This was the first time an architectural structure was used in this manner. He was a PhD in mathematics said to have been a type of genius with unlimited potential. In his cabin at the time of his arrest there were about 300 volumes of books covering history, politics, theory, philosophy, science, and religion – basically the canonical texts of western history. He had a particular interest in Henry David Thoreau and his ideas of independence, living in nature, social experimentation and self-reliance. Kaczynski’s cabin in Montana was an identical copy of Thoreau’s cabin at Walden Pond where he lived out the exact life that Thoreau preached in his books. If the cabin in Montana were proof of Kaczynski’s madness and subsequent conviction then it would be logical to conclude that Thoreau was equally insane living in exactly the same cabin structure. Through a form of reverse engineering from the photos of the cabin I built an exact copy of the cabin Kaczynski lived in.

To this I added Martha Stewart, a recent celebrity. At the time, Stewart was the undisputed queen of domesticity, the home environment perfected and a brand and icon of beautiful living. Surprisingly, Stewart and Kaczynski had a number of things in common: they are very close in age, both received advanced degrees from Ivy League schools, and both are Polish Americans. Both are the contemporary examples of extreme choices made by living in the American empire. If Kaczynski was the genius mathematician who made a conscious decision to become an active revolutionary engaging in wide ranging social and political critiques then Martha Stewart was the one who decided to become a business woman embracing consumerism and an advanced capitalist model for corporate global business ventures of publishing, broadcasting and merchandising that have accumulated into Martha Stewart Living Omni media, a multi-billion dollar empire. The two are polar opposites in politics and ideology. They were at war with each other and never knew it. In other words, what they each came to represent was at war. Both are failed models of what’s possible through American independence and what’s fundamentally wrong with the arrogance, morally corrupt, ethical hypocrisy, totalitarian, exploitive government and economic systems in the United States and now the global free market.

These two represent the collapse of so-called American democracy and living in a market driven society. It seemed I had one of two possible solutions for this sculpture: take them both out and publically execute them in high definition global broadcast television as a response to this type of exploitation and abuse, or marry them to one another. I decided the latter since it was a non-violent and more poetic solution. I took the raw reconstructed cabin of Kaczynski and used the colors of the year (2004), from Martha Stewart Living. I took the color chips from her exclusive paint line - which are in some ways similar to the Pantone colors of the year - and applied her color theory and principles of the perfect use of color. I painted his cabin in color-coordinated beauty in order for it to be in absolute harmony with nature. To me, this was the marriage of radical political action and sublime domestic bliss. Two extreme views of life married into one ideological structure rendering an exquisite image of contradiction and contemporary social/cultural corruption.

GV:

This piece speaks on so many profound levels regarding fundamental American values that I’m wondering how it would have been read outside of a purely American context. Speaking of which, I’m wondering if your working process is different once you move out of the U.S. “empire.” I’m thinking of a few really great instances and will start with the 2004 project you realized at the San Juan Triennial called, If Only God Had Invented Coca Cola, Sooner! Or, The Death of My Pet Monkey.

DJM:

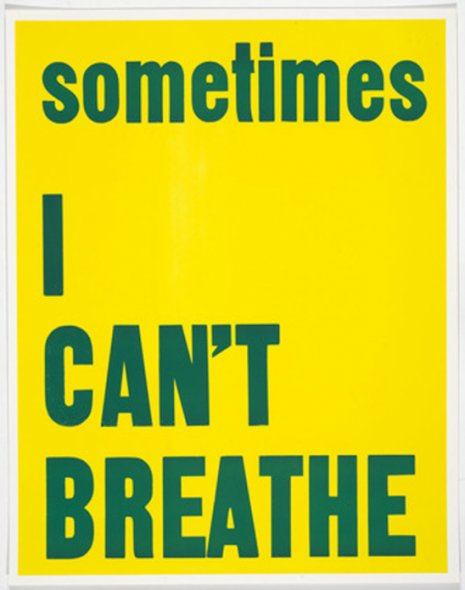

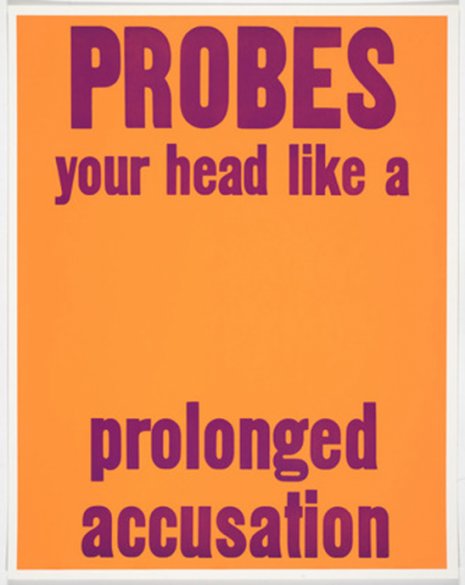

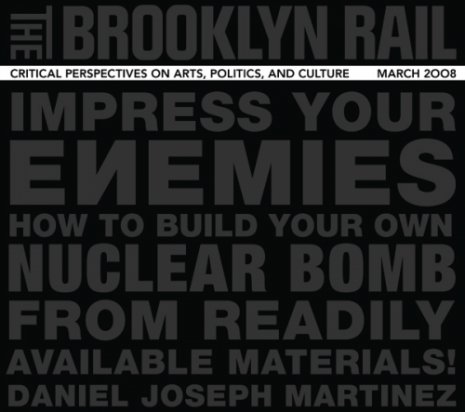

There are many great advantages to be had working inside the empire, but simultaneously it’s like having one’s hands tied. Subjects and topics that are at the point of crisis, catastrophe, disaster, and social extremity are mostly denied, avoided or outright dismissed in the US context. By contrast, most the world anticipates the debate and discourse that can be brought to bear by artists and the work we produce. Nonetheless, we persist in directing our analysis and critique towards the geopolitical and the movement of power relations as they are played out through the political institutions represented by the interactions in the 21st century global environment. The project you are referring to in San Juan was another experiment in attempting to combine a number of different modes of production and interaction. I began the project by spending time in San Juan, and, at the same time, was working on a set of 24 wood block prints with the Colby Poster Printing Co. here in Los Angeles.

These posters are quintessentially part of the LA urban experience and posted on every corner. With bright florescent colors and large unusual fonts, they advertise clubs, music, events, protests, things for sale, political elections, and holidays. The posters are used to make public statements of different kinds and are a longstanding method and still a very effective form of communication that is indelibly inscribed into the car culture landscape of LA. These posters seemed like a perfect vehicle since San Juan is both a city that one can walk in and also one of cars. I had discovered a favela called La Perla, which at the time was listed as the most dangerous favela in the Caribbean. I found this amusing and a perfect example of the fear of the Other. Ghettos and favelas are just other people’s neighborhoods, usually very poor, and the projection of numerous types of stereotypes and fears become amplified.

La Perla is a very interesting place for a number of reasons; it’s on a thin long strip of land situated outside of the great wall that surrounds San Juan. The favela is located right on the beach itself between the exterior of the wall and the ocean. It’s exquisite and beautiful beachfront property with views of the Caribbean. There are endlessly sublime, watery vistas of greens and blues that can make you cry. Since this is someone else’s neighborhood, I spent considerable time getting to know the various local leaders and senior residents, and asked them if I could be an artist-in-residence and create a site-specific work throughout the entire favela. On a daily basis I would post my 24 text-based poetic prints on homes, businesses, and trees. By placing them everywhere I believed I could intervene into the existing landscape. After several meetings and much discussion and looking at the artwork they agreed. This was very exciting because I was given free rein to go anywhere, anytime of day or night, to post my prints during the course of my time there. The favela itself was large enough that it was never going to be possible to visit the entire neighborhood. That was also the challenge: to see how many I could get up at the same time throughout the entire favela making it one large poetic text-driven piece of urban space with these florescent colors from Los Angeles contrasted with the colors of the ocean and the sky. Along with the palette of the colors of the neighborhood homes, this made a beautiful and dramatic combination.

The placement combinations were endless and it became a very challenging and exciting process to figure out. Each day’s outing, whether day or night, provided a new challenge. I very quickly noticed, as I was posting the signs in one area and then moving on to the next, that the signs would be missing from places where I had just posted them. At first I couldn’t figure out how they were disappearing. I asked a friend I made there, and he told me the residents were so happy having the artwork around that they decided to collect them for themselves as a keepsake of the project for after it was over. This created an interesting new challenge: how to get the posters to stay up long enough to create the effect I wanted but still allow people to be able to collect them for themselves.

I had a meeting with a few of the residents and asked if we could put up the work and ask people to leave them up for a few days before collecting them. I asked for volunteers who would like to help me put up the posters and ended up with a fantastic crew of young and old who wanted to participate each day. Some people took part daily, and there were always new people too. Throughout my several weeks in residence I must have posted around 1,500 pieces. In the end I got to know so many people going about their daily lives who had been seeing me everywhere all the time. I was the first artist to come and interact on a very direct and cooperative manner. In a sense I became a part-time resident of the favela. This was nothing short of an extraordinary experience for me, all of it, the performance of placing and posting the prints, interacting with the residents, making the text prints in LA to bring them to this island paradise in the Caribbean.

It’s very hard to quantify but something in me changed after this. In many ways I was not the same person when I began the project primarily because of my relationship with the residents of the favela and their generosity and enthusiasm towards my project. This relationship enabled me to experience my own work in a new way. The whole project carried with it the politics of race, class and economic struggle along with a stance of revolutionary ideology in the form of language as poetry in a public/social space that had been activated in new and unpredictable ways. Truly this was poetic terrorism performed in real time with an entire neighborhood involved and participating. I saw it as an active form of political aesthetic intervention that was unknown and unpredictable, existing in time and space as an agent of love.