In Guadalupe's Words...

To accompany my past exhibitions, I’ve developed participatory programming that draws from my own experiences with illness, alternative healing practices, migration, and political strife.

When I was eight, I fled my home country of El Salvador, then embroiled in civil war. I arrived, unaccompanied and undocumented, at the United States border in 1984. In 2006, I became a citizen and in 2016 to commemorate the occasion, I changed my name to Guadalupe Maravilla in solidarity with my undocumented father, who first took on the surname “Maravilla.” As an acknowledgement of my own migratory past, I ground my practice in historical and contemporary immigrant cultures, particularly those of the cancer and undocumented communities. The story of my own displacement from El Salvador to the United States recurs throughout my work.

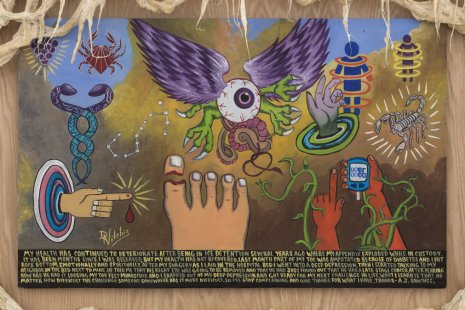

Often, this narrative is embellished, or elaborated in a fantastical vernacular. Autobiography is presented in tandem with pre-colonial Central American ancestral myths, handmade objects, drawings, and other border-crossing narratives.

I draw parallels between the violence endured by asylum seekers today and my own border crossing experience in the 1980s; my untreated physiological stress contributed to me getting colon cancer, which I overcame in 2013.

In March 2017, I performed Boom! Boom! Whammm! Swoosh! at the parking garage of the GOP headquarters in Austin, Texas as part of the FUSE Media festival. In this performance, I conducted a San Antonio-based feminist motorcycle gang inside the parking garage as though they were an orchestral body. The empty garage served as a vessel for protest, amplifying the sound of the roaring motorcycles and the screams of participating audience members. I also directed both the sound and the movements of twenty-plus immigrant performers, all of whom were, and still are, directly affected by our current political climate. These participants included quinceañeras, Tibetan throat singers, and immigrants with disabilities. In a sense, the empty parking garage was transformed into a giant therapeutic instrument, intended to cleanse political phobias in the audience or to decolonize the space. The vibrating Harley Davidson motorcycles served a similar function as a therapeutic Gong Bath.

In July 2018, I exhibited a series of drawings, Requiem of My Border Crossing, at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York as part of the exhibition titled Pacha, Llaqta, Wasichay: Indigenous Space, Modern Architecture, New Art. I began by investigating 16th century Historia Tolteca Chichimeca manuscripts, which originated in the Southern region of Mexico—one of my many stops along my migration route into the United States as an undocumented child. Originally written in Nahuatl, the manuscripts describe various rituals, and the symbiotic relationship between the land and indigenous communities during colonization.

From there, the 16th-century manuscripts were scanned, digitally rearranged, and hand-drawn into new documents. The new drawings depict crossing routes, indigenous rituals, dwellings, rivers, plants, and the displaced Central American Mestizo and indigenous communities. I resolve the drawings by playing the collaborative drawing game Tripa Chuca with members of the undocumented community, overlaying the existing composition. Tripa Chuca is a Salvadoran childrens’ drawing game, in which participants draw lines connecting pairs of numbers, without crossing the previously drawn lines. The outcome of the game determines the form of the final drawing, which ultimately serves as an index of a collaboration of two individuals re-staging a story of migration. I used this collaborative drawing game to create both the wall murals and the works on paper in the exhibition.

As part of same presentation at the Whitney, I performed The OG of Undocumented Children. This performance incorporated autobiographical storytelling and invented rituals, executed in collaboration with nineteen immigrant performers. These participants included: a family of immigrant vampires who only drank blood of Americans; three masked quinceañeras; the Mexican gothic electro-drama band La Rubia te Besa; two futuristic coyotes (a name used for a person who is paid to bring undocumented people across the Mexico–United States border); a pair of soothsayers, a La Momia songstress, and myself, the protagonist of the border crossing story. All performers were immigrants, some of whom were undocumented youth (DACA recipients only, to ensure their safety) that I encountered by connecting with New York immigrant communities for many years.

In 2019, I began Disease Throwers, a series of sculptures that function simultaneously as headdresses, healing instruments, and shrines. I collected the raw materials that comprise the works as I retraced my own migration route across Central America to the United States. Plastic anatomical models relate to illnesses in my family, and instruments such as conch shells, flutes, horns, crystal pyramids, gongs among many other objects adorn each headdress. The sounds produced by the Disease Throwers operate as vibrational healing treatments that wash away anxieties and help communal healing. These sculptures have been activated during sound baths in museums and community spaces nationally and internationally.

Oftentimes, my sculptural and performance works include an interactive, pedagogical component. In these workshops, I invite institutional and community audiences to engage with ritualistic usages of sound and movement, in order to facilitate mutual healing. In the past year I developed solo projects at MoMA, Brooklyn Museum, P.P.O.W gallery, Henie Onstad Art Center, and Socrates Sculpture Park in New York.

In December 2020, I would have debuted my Creative Time project SPIRIT LEVEL at the New York Hall of Science in Corona, Queens, New York. Unfortunately it was canceled due to COVID-19. The centerpiece of the exhibition would have had three 12-foot pyramidal mounds made of Central American household pantry staples, including maseca (corn flour), rice, and beans. There would have been around 32 tons of food in total, presented alongside two newly-commissioned Disease Throwers sculptures. While in the past, these works have resembled headdresses, these new sculptures resemble vibrating tables that respond to the sounds produced by the gongs. The surface of the tables will be covered in medicinal flowers. These sculptures accommodate an individual with hearing disabilities, who is able to experience the sound bath by laying on the sculpture and feeling the sonic vibrations. The project responded to food scarcity caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, as the 32 tons of food was donated to food banks and churches after the completion of the project. Unfortunately this project was placed on hold in the hopes that it can reemerge in the future.

In the future, I hope to expand my practice by building sanctuary spaces all over the country. These sanctuary spaces will function as community centers, food banks, and schools that will teach ancient and holistic healing methods, allowing participants to learn to heal themselves. These spaces are intended to provide marginalized communities with much-needed resources for wellness, so that they can obtain long-term self-awareness, and achieve mental stability in their lives. In these artist-run spaces, Disease Throwers sculptures would be used for sound baths. These spaces will specifically serve undocumented children and families that have been separated from each other.