Other Composers and Musicians

IB:

Are there other composers/musicians of interest to you who bring together technology, experimentation, and African music?

LL:

While extremely few people bring together technology, experimentation, and African music, quite a few people, often in teams, work with technology in African music, though almost exclusively in the pop field; these teams tend to include one (rather traditional) African musician and one (rather technologically inclined) non-African, such as in the case of Issa Bagayogo and Yves Wernert or Mamani Keïta and Marc Minelli.

My own group Burkina Electric is no exception in this regard, as the technological side is brought into the mix by the two non-African group members - myself and Pyrolator, who is from Germany. But rather than taking traditional music and superimposing electronics onto it in a remix-like aesthetic, we compose our music collaboratively from scratch and build in the electronics from the beginning, so that the presence and the manipulation of the electronics becomes part of the African group members' vocabularies as well.

In general, however, the remix aesthetic does still dominate, and the domain of Afro-electro crossover has been populated by DJs such as Frédéric Galliano with his Frikyiwa collection and all the DJs who have worked with the South African group Amampondo. And then there is African hip-hop, which has taken over the continent; especially strong scenes exist in Senegal and Burkina Faso among other places. And, of course, there are special regional variants of house music and electronica such as coupé décalé in Côte d'Ivoire, hiplife in Ghana, kuduro in Angola, and kwaito in South Africa.

The combination of African music and experimental music is a smaller field, with the definition of "experimental" obviously up for discussion. There are composers in Africa who have worked on fusions of African traditions with Western concert music, with the greatest concentration in South Africa, including Jeanne Zaidel-Rudolph, Kevin Volans, and Peter Klatzow. Perhaps the originator of this direction is Kwabena Nketia from Ghana; there are many important Nigerian composers such as Akin Euba and Joshua Uzoigwe, and in East Africa, there is Justinian Tamusuza from Uganda.

There aren't many composers from outside Africa who have been seriously influenced by African music and its concepts, which, is, I must admit, very surprising to me. Steve Reich, Conlon Nancarrow, and my father, György Ligeti, come to mind; all have influenced me greatly. But in the case of all the above-mentioned composers, with the exception of Nancarrow, the African elements are not treated in ways that use technology.

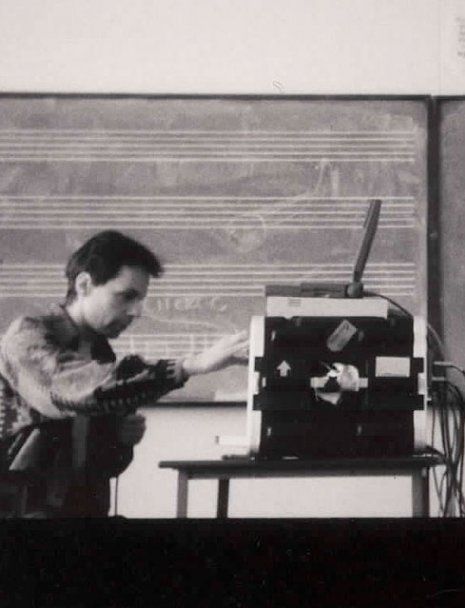

When all three come together - Africa, experimentalism, and technology - the field becomes tiny. Halim el-Dabh, from Egypt, is very important. Using a wire recorder in Cairo in 1944, he created perhaps the first electronic music in Africa. More recently, there are electronic experimental composers in South Africa, such as Jürgen Bräuninger, Ulrich Süße, and Dimitri Voudouris. Voudouris made an important contribution by organizing the first festival for experimental electronic music ever to take place in Africa, the Unyazi Festival in Johannesburg in 2005, where I had the pleasure of participating. And there are unusual individualists and groups in Africa who have used electronics in unconventional ways, for example Konono No. 1 from Kinshasa.

I'm sure I've left out many important people. But given the amazing potential for creative work, I am still puzzled how small the field is.