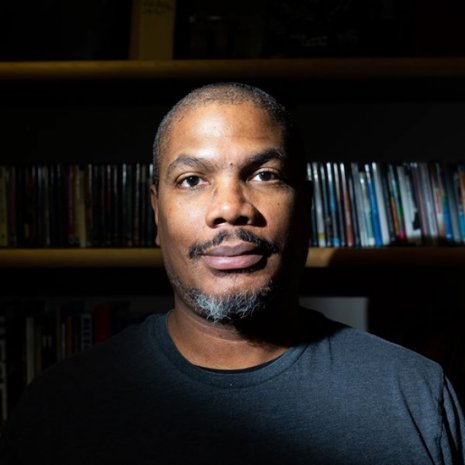

In Christopher's Words...

By subverting conventional documentary filmmaking practices, I hope to lay bare the power dynamics at the core of cinematic depictions of the real. My films trouble the notion of documentary truth and interrogate the ways in which cinema’s ability to capture appearances is inseparable from questions of power and the West’s hegemony over Black people and cultures in North America.

Low-tech, lo-fi filmmaking methods and tools are central to my creative practice which exploits the expressive potential of analog film’s material imperfections and imprecisions. Working through incongruity and slippages, between sound and image, multiple pasts and present possibilities, and notions of fact and fiction, my filmography engages the complexities and paradoxes of Black experiences in the United States and the wider Black diaspora. My purposeful use of photochemical irregularities, creative misuse of the camera, and distressed celluloid filmstrips aim to disrupt the technologically imposed transparencies of rationalized temporalities, circumscribed spaces, and policed movements which I see as integral to racial capitalism’s visual culture regime.

I want my films to assert their material presence as sound-image objects that channel the ecstatic experience of Black refusal, survival, and rebellion. My Black ecstatic cinema is a form of what Saidiya Hartman calls “black revelry and riotous disorder, fugitivity and temporary autonomous zones without a fidelity to the prevailing or imposed script of the possible.”

I place my filmmaking practice within a tradition of African American cultural production employing collage aesthetics. These collage practices come from across a range of artistic mediums such as Ishmael Reed’s Neo-HooDoo literary remixes of historical fact and fictive imagination, the Art Ensemble of Chicago’s Great Black Music Ancient to the Future sonic montages, Bettye Saar’s arrangements of found objects and assemblages and Romare Bearden’s photomontages come to mind most immediately, not to mention, Public Enemy’s It Takes and Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back and De La Soul’s Three Feet Hight and Rising. These artists unabashedly mix and match sources and materials, juxtaposing them together in ways that manifestly do not fit neatly and seamlessly together.

Similarly, my work draws from the sonic and moving image archives and recombines them in startling and uncanny ways to highlight their status as fragments which, when placed side by side, refuse the production of master narratives, historical closure, and temporal/spatial coherence. Per Tina Campt, refusal in this sense means “a rejection of the status quo as livable and the creation of possibility in the face of negation i.e. a refusal to recognize a system that renders you fundamentally illegible and unintelligible; the decision to reject the terms of diminished subjecthood with which one is presented, using negation as a generative and creative source of disorderly power to embrace the possibility of living otherwise.”

About work (stills and embedded clips):

My film still/here (2000/01) employs a static camera, shots of long duration and asynchronous indeterminate sound/image relationships to essay an interrogation of the Missouri Historical Society and the St. Louis Architecture Museum as extensions of, and coterminous with, the ongoingness of material, economic and carceral extraction as well as African American abandonment inscribed on the landscape of north St. Louis’ vacant lots and crumbling, collapsing Victoria era brick homes. My approach to making this film was to reject the way that the dominant visual culture puts so much representational weight on the bodies of Black people while simultaneously holding Black people in contempt. My response was to make a film about the putatively abandoned spaces that Black people had once inhabited and loved. I wanted to look with love at these spaces that are so degraded, despised, and uncared for. still/here lavishes a deep, loving gaze on places that weren't ever supposed to be looked at ("eyesores") -- much less regarded with anything like love.

This film grapples with the experience of something like a simultaneous radical presence and a radical absence. The temporal relationships in the film are slippery and undecidable, that is, it isn’t fully resolvable as to whether the sound is the ghost of these spaces in the images or if they are a premonition of them. One tends to read ruins in terms of pastness so it’s tempting to read the sound as the ghost of these spaces. Ultimately, however, the temporal relationship between sound and image is not decidable when they are congruent or adjacent to one another but not synchronized. Ruins are like a bit of the past in the present, and cinema functions in a similar fashion. Cinematic images and sounds are fragments of prior time and space in the present moment of the screening as the viewer watches, so it collapses this binary between past and present. I think that is the experience of watching any film. Many films are constructed so as to efface that experience and provide the sense that the events one sees are happening right now, but I wanted to make a film where viewers are constantly aware that the present cannot cover over the past.

In her book chapter “Between Documentary and the Avant-garde: Exploring the Visual Poetics of Ruins in Christopher Harris’ still/here,” Terri Francis writes about how in the so-called “hood films” of the early ’90s—like Boyz n the Hood (1991) and Juice (1992)—the urban landscape is inscribed as a setting for the dramatic narrative. Francis points out the reversal of those roles in still/here: relegating the drama, narrative, and actors to the background—or absenting them altogether—and bringing the setting forward in order to see it anew. I believe that this extreme reversal makes it difficult to watch the film without being quite conscious of your position as a spectator in relation to the film.

In 2019, I was extremely proud to present still/here at the Locarno Film Festival as one of the 47 films included in the Black Light Retrospective programmed by Greg de Cuir Jr. I remain humbled and inspired by the inclusion of my film in this "unprecedented overview of Black film in the 20th century" featuring the films of Oscar Micheaux, Charles Burnett, Shirley Clarke, Ousmane Sembène, Kathleen Collins, Julie Dash, and many other global icons of cinema.

Reckless Eyeballing (2004) juxtaposes eyeline matches showing characters in D.W. Griffith’s silent film era Birth of a Nation (1915) and the 70s blaxploitation film Foxy Brown (Jack Hill, 1974) meeting one another’s gazes, effectively gazing back and forth across a span of more than 60 years of film and U.S. history. Throughout, the film weaves together text, sound and imagery sourced from the film The Medusa against the Son of Hercules (Alberto de Martino, 1963), the FBI wanted poster for Angela Davis, Paul Robeson’s 1944 performance of Othello, an unknown self-help book from Florida’s Orange County Public Library, a cinematography textbook, and a recording of Robert Louis Stevenson’s poem My Shadow. By transgressing boundaries between cinematic genres, temporalities, light and shadow, Reckless Eyeballing materially and formally enacts the potent mix of dread and desire around the figure and body of the Black outlaw in the American racial imaginary.

In Halimuhfack (2016), performer Valada Flewellyn lip-synchs to archival audio sourced from the Library of Congress’ Herbert Halpert 1939 Southern States Recording Expedition collection featuring the voice of author and anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston as she describes her method of documenting African American folk songs in Florida. By design, nothing in the film is authentic except the source audio. The flickering images were produced with a hand-cranked Bolex so that the lip-synch is deliberately erratic and the rear projected, grainy, looped images of Maasai recycled from an ethnographic educational film become increasingly abstract as the audio transforms into an incantation. Halimuhfack embodies the complexities and paradoxes of knowledge production around African cultural retentions among African Americans. This film was the subject of an incisive in-depth analysis by Jaimie Baron in her essay "Christopher Harris's experimental audiovisual historiography" which appeared in the book "Images in History: Towards an (Audio)Visual Historiography."

Dreams Under Confinement (2020), a short video about Black breath and breathlessness that was commissioned by the Wexner Center for the Arts, is my first foray into video making that was made using only what I could access from my computer desktop. The pictures are taken from Google Earth/Street View and the audio is taken from a YouTube video of transmissions by a Chicago Police Department radio dispatcher during the 2020 uprisings in response to the police and vigilante murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery. The prison and the street merge in a shared carceral landscape as the video rapidly intercuts stock images of aerial and ground views of Chicago city streets called out by the dispatcher and the Cook County Department of Corrections. The CCDC is ninety-six acres and 8 city blocks-- one of the largest single-site jails in the country. Approximately 100,000 individuals circulate through the jail annually. Dreams Under Confinement is dedicated to everyone behind bars in the U.S., a population that is especially vulnerable to COVID-19.