Chapter Three

VM:

I think the experience of attention is quite different in a theater and in a museum. In theaters we are one of many, in a space where spectator and performer are separated, and usually at some distance. My experience of seeing your work in a gallery space was that I felt myself/my body implicated as a performer, and the real performer, was in relationship to me. In the museum, the definition of stage space and spectator space became slippery, and delicious. When you are performing in a gallery, do you ever feel that you are in a duet or ensemble dance with the audience?

MH:

There are differences in the kind of attention paid to live-performance works in theaters, museums, and even public spaces. Even so, works can be presented in these various contexts using similar approaches; for example, presenting a work in a museum that has a specific duration—similar to the duration works have in theaters—with a clear beginning and an end, a dramaturgical through line, and fixed seating for the audience. In this case (and I have done so myself on a few occasions), pretty much the only thing that changes from a theatrical presentation is the overall color and scale (black box versus white cube). Within this approach, the attention required by the audience remains pretty much the same.

A good friend mentioned to me a while back that in theater we tend to treat the audience as “one body.” You cannot consider each audience member individually. While in a gallery or in an open space, this doesn’t have to be the case. Within the constraint of not having a framed beginning and end, the performer is not aware when a visitor will enter a gallery, when they will pass by them, or how the visitor will choose to behave. This changes the intimacy between performer and viewer, and even the work’s intensity and temporality. But definitely in a gallery/museum setting, there’s a feeling at times that we are performing for just one person, and I think this can be quite luxurious for both the viewer and for the performer.

VM:

I did not notice that your recent performances at the Hammer had a dramaturgical through line, or even a clear beginning or end. I might be misunderstanding you.

MH:

My recent work at the Hammer was set in the format of a “live-installation”—which does not treat the museum within the tradition of theater.

In the past few years I've developed a slightly different approach when creating works for museums, one that I call “live-installation,” which as a principle has no dramaturgical beginning and ending apart from the opening hours of the institutions. Right away, this aspect shifts the quality of the work, since there’s no definitive arch in its duration. Museum visitors often come upon the work without expecting it. Some neglect us; others get intimidated (it is the body after all, and unfortunately sometimes it is still a scary taboo). Others allow themselves to get involved and even be touched by our proposal.

I’m interested in this “ongoing” presence in the museum, as it relates to the attention visitors give to all art exhibited there. I also find this approach democratic somehow, as it’s up to the individual to decide in what way to view and for how long. In the meantime, we are there, and are fully committed to our product beyond the un-scripted interactions that may occur.

There is a through-line in my works despite the context of presentation. They all tend to be rather quiet. Always present is the sculptural physicality of the body, the stillness we acquire as performers and the paradox of this stillness, as well as a particular velocity. What shifts are concerns of duration, whether there is a clear beginning and ending, and the approach to addressing the audience.

VM:

Do you look for a particular kind of performer? What are some of the qualities and differences they bring to the work?

MH:

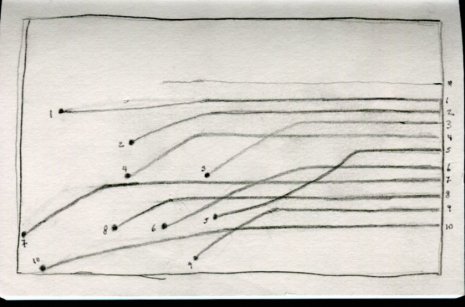

This depends a lot to the project I’m developing, on the needs of a work: will it be technical or more performative? In general, I like to work with the same people as much as possible, as it helps the continuity of the work grow as a dialogue amongst us. I’ve collaborated with Hristoula for 12 years, with Robert Steijn for 5 years. It’s important for me to engage with performers who are interested in specificity, those who can let themselves be immersed in detail during the work’s process and presentation. This can be crucial because, as you know, some of the works are performed daily over a long period of time, and a detailed approach is what keeps the performances alive and keeps the performers from boredom… Apart from this, I love working with different individuals who come from various backgrounds as this offers a richness to my work and I’m curious to uncover the possibilities each person brings.

VM:

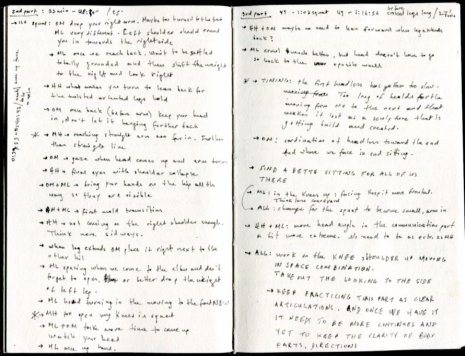

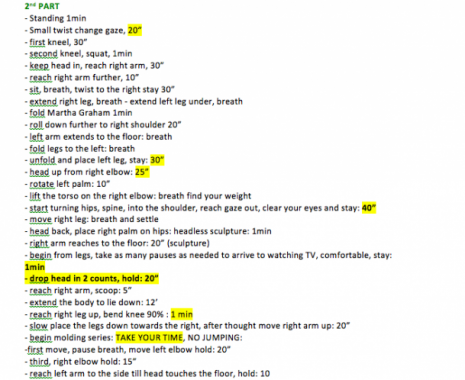

Do the performers have much leeway in your work? What is scripted, and what is porous? What is spontaneous, and where is the plan?

MH:

The “plan” is usually very strict. And yet, yes, there’s leeway for each person involved to express themselves in their own individual way.

I feel uncomfortable when I enter an empty room full of chairs and I have to be the first one to make a choice of where to sit. I’d rather walk into a room with only one chair empty (even though it is quite claustrophobic at times) and then try to make that space mine. It’s a bit like my choreography. What is usually given to the performers is a very strict, even rigid, script and it has to become personal in how they inhabit it, how they fill it.

VM:

Finally, a few more questions. Please tell me about working internationally.

MH:

In a way I’m curious in presenting my works in wide variety of contexts, it is also important to me to see how works translate in different cultures—placing the work in contexts that are new, away from safety zones of ones own community, and seeing how people react. I’ve learned so much, and continue to learn, from my travels and the audiences I’ve shared my work with. I feel very lucky for these opportunities.

VM:

What’s an ideal working state/environment?

MH:

Time and space. For the past 15 years I always had my own studio and that was crucial in developing my work, as I could be as immersed as I needed. I need time alone to work through ideas and concepts, and then have the collaborators join the process. Ideally I prefer taking the dancers off their NY schedules and having focused periods where we can dive deeply into the process together.

VM:

How long does it take to develop a piece?

MH:

The actual making of the work takes approximately 6-10 weeks, working intensely for long hours. But before arriving to the “making,” the process has already begun a year, and in some cases even two years before: the research phase, finding the space, casting, organizing residencies and securing funding.

VM:

Do you video your work while you're working?

MH:

I work with video daily during the process. It is a tool that helps me understand the work and it is great for the editing process.

VM:

And what you're working on now?

MH:

Touring my older works. Adapting PLASTIC in its two further iterations, at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, and the Museum of Modern Art in New York (with the presentation at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles having its premiere in January 2015). And beginning the research and preparation of a new work for the theater.

VM:

What generates pieces these days?

MH:

I want to make my work. I want to make new works. And I want to present them. I love beginning something new and slowly seeing it come to life. There’s curiosity attached to this that keeps me very excited, that doesn’t let me rest till it’s figured out - and yet the process of problem solving feels very fulfilling to me. Through the years I have developed a format for my work and a set of questions I’m exploring. This format was not something I tried to invent consciously: rather, it happened naturally as I was diving deeper into my process. Having this format makes it much easier, of course, as I don’t have to reinvent myself each time I begin creating but rather, continue.

***