Chapter One

This conversation between Dohee Lee and Adam Fong,* composer, and co-founder, Center for New Music, took place in San Francisco, on March 9th 2016. It has been edited.

Adam Fong:

I know you’ve recently finished up a large project at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts. What’s coming up next?

Dohee Lee:

The project I premiered at YBCA is called MAGO. It’s about my hometown, Jeju Island, South Korea, and my ancestors and the present issues that people are dealing with there. I took my personal story and created a mythological journey - like a superhero story. Now we’re getting ready to tour MAGO in different forms in 2017.

The next project in development is called Waterways, Time Weaves. It uses a similar process of personal mythmaking that arose from the development of MAGO, but it’s no longer about my life. I’m applying this approach to other people’s voices and stories. I felt it was very important to give time and space so people can talk about their own stories. I’m working with a specific community now, through API's Women's Initiative, composed of mostly immigrant woman and refugees.

AF:

They’re based in Oakland?

DL:

Yes. I started working with them last year; we’re creating a program together. There are over 100 women, ages 16 to 70. Through workshops we are exploring their stories. I was thinking: how do I collect their stories? How am I going to involve them? How do I want to weave them into and through the stories that they're going to carry out?

AF:

What kind of stories are you hoping for or expecting?

DL:

I really value myth. Old myths and also, creating new myths. People begin by telling the story that they feel is strong and important. As the stories are passed down mouth to mouth - writing them down came later - the heroines and heroes of these stories become mythical figures and God or Goddess figures. The people valued these figures and this value gains meaning and importance over time and that myth can become a blueprint for how to protect and sustain the community.

If we understand how myth emerged in the past and in our present time, we can look for those modern stories that can present a bridge to creating new myths. We can do this through our work and this project. I want to keep that alive for people, so that mythical journey and personal journey can go together.

AF:

Is the starting prompt: “talk about why you left?” It’s all first generation stories?

DL:

I'm asking people who are recent newcomers, who have been here between one month and ten years. I am hearing their stories and learning about the dreams they had before leaving. We are touching the dreams that brought them here: What were the things that you thought? What was the dream?

It’s all about how America is a dream country. (Laughter.)

AF:

When you're coming to it, definitely.

DL:

I came here for my dream. You have to work a lot to get the dream. Sometimes you do work that you never expected to do. I want to face those parts, too. “What was the dream that you couldn't really get close to? And what is your struggle in this present moment?”

AF:

That could mean so many different things.

DL:

I am thinking about how to structure their stories from the myth to their dream, and their struggle to find hope. We cannot just talk about it. We have to take action. Doing this performance piece is about action, and creating the space to really think about what we need to do. One of my intentions for doing this performance with a community is to ask these questions. “What is the voice that you never spoke? That you need to speak? What are the things that you never confronted?” We need to address this.

AF:

Your training and background is in performance skills in music and dance. And I know that in the modern art world it's easier to understand those disciplines than it is to understand the practice of asking questions, or interfacing with community. But when you're asking people to share their stories, it's very explicit and it's about language and the way language can communicate or build a myth or convey an experience. How do you see activating other people’s bodies, bringing in those tools that are beyond storytelling?

DL:

I’m thinking about the different media, and I encourage them to use their own language.

AF:

Oh, so you probably won't understand the language for many of them.

DL:

For me, that's the music. When you are listening to the language itself, it's amazing how the intonation, the repetition of words creates feelings and emotions and becomes the music. All these different languages become the music like a chant – Bhutanese, Burmese, Cambodian, Korean, Mongolian, Nepali, Tibetan, Vietnamese…

The people are telling their stories in their own ways, many people at the same time. The story of them leaving their countries is really a hard story. How many people really leave their country with happiness? They have many different reasons that they had to leave. I’m taking in their grief and the story that they have told. I’m taking it into my body, and doing the music piece as a weeping song. That's a very traditional Korean concept. When people die, part of the funeral process is to hire the weepers. Traditionally, in Korea, the mediator of the ritual is the shaman. This mediator comes out and takes all of the people’s stories into their body. This is becoming “Weeping Song.” The

performance is structured like a ritual.

AF:

And there's an embodiment of that feeling.

DL:

Exactly. The professional weepers cry and then the people cry. The weepers are doing a tremendous job. Because it’s easy for people to suppress their feelings and emotions.

AF:

They can't release completely.

DL:

These weepers help that. They’re crying for you, and so you can cry. That is the deeper meaning.

AF:

That’s such a powerful position, the weeping song idea. And you’ve put it right next to the immigrant experience, which, like you said, is often painted as a moment of hope and a moment of optimism, the expectation that our country will provide something that a former home wouldn't. Even when it's an exile situation, or someone’s escaping violence or poverty, there's still that hope that it's going to be safer or better.

DL:

But people don’t see it; we still hide that. So I bring that need to cry into the piece. You know, our mother cried for us. I think about how we can take a mother’s weeping sound into a piece in an artistic way.

AF:

Why do you think we need it?

DL:

I picked that very carefully and intentionally, because if I just touched on the present moment of when people leave their country, it might not make sense to talk about immigrant stories. My intention for bringing their stories is to bridge the past, present and the future.

I’m bringing up all the history. Before, this land was natives’ land. I want to go back to this. The crying is really necessary because we have to be aware of this. We’re forgetting everything about how this country was built. What did all the immigrants bring from other countries? Because there's always tension there. War was happening, is happening and will be happening. And what’s happening here is immigration because the conflict and tension between the countries.

That’s how I see my own Korean history of immigration here. First immigration wave was to sugar plantations in Hawaii in 1903 during Japanese occupation in Korea, and the second wave was Korean War in 1951, and that has come all the way to the present; now there are different reasons people immigrate and this will change the future as well but immigration stories are continuing.

AF:

Right; situations like this became the pattern for our country.

DL:

Exactly, that’s the pattern. And every country that the immigrants come from has seen a pattern of some difficulties. So in the difficulties, we try to find the laughter and happiness, but the beginning, when you first really face it, it's really hard. It's really sad.

As a recognition of that fact, and also in creating of the myth, I thought a weeping song makes sense.

AF:

Mm-hmm, it's a piece of the process, for you, as well as them, probably.

DL:

Right, right, just recognizing who has come before us creates why you're here, and who is the next generation. We can make all the connections between the different generations: why they were here, why am I here, and why this is important for the next generation.

Knowing what circumstances that I am dealing with – understanding time, place – understanding my story – is so important before moving towards a result or solution. Because if we do not know clearly why we have this pain then just asking a doctor to prescribe the medicine will not work at all. My creative process is that the story itself becomes the medicine. Medicine is inside of the pain, inside of tears, inside of struggles. That is why I think sharing and speaking stories is a powerful method to take action. And if we can create this through art, we can glimpse ancient time and life.

AF:

It's really interesting for me to hear about that coming after MAGO. That project seemed like it was triggered by going back to Korea, and maybe revisiting a lot of the reasons why you left, and what’s happened in your former home in the interim. How do those two things relate to each other, for you, in the creative process?

DL:

Well, it was very connected. I was researching in my hometown, Jeju Island, focusing on two things: one was the massacre that happened, and another is a naval base that is being built in Jeju. Both are deeply connected with the U.S. Army. In Korea, the military side of the government is interconnected with America. It's not Korea’s own decision to build a base. Even the massacre, too. A lot of power came from here.

AF:

Part of the larger battle.

DL:

Exactly. You see the big picture of who is the puppet master and who are the puppets.

AF:

Have you ever done more explicit political advocacy work, or is that out of your interest area?

DL:

No, I’ve always been involved with it. My work could be political. But I don't think of myself working in that way. What I do care about is what’s happening in the land, people, the environment and also spirituality. It’s always involved with political, economical, and ecological issues.

Because this is a performance ritual and ritual has a purpose. You have a clear reason to do it addressing messages that are urgent or doing some actions that are desperately needed. I have to do it. It feels like it's not my choice anymore! (Laughs)

AF:

The way that you're developing this next project, working with other people’s stories, and taking them through a process and a ritual... I've heard you say that the outcome and purpose is really about healing.

Is that something that has always been there in your artistic life? How did that come to be so important to you?

DL:

That's a very good question, because I wasn’t like this when I was young. (Laughs)

AF:

What were you like when you were young?

DL:

Well, I wanted to dance; I wanted to play the drum and loved heavy-metal music.

AF:

It was joyful, probably.

DL:

Very joyful. And focused on a lot of technique. I wanted to learn this and that; I wanted to learn Korean folk music, Farmers music, court music, shamanic music, traditional dance, modern dance, ballet and drum set.

I still love performance. I love playing music and singing and everything. But at some point it shifted. There were many things that hinted at me as callings through the body, drawings, writings, movements, people, teachers, music, concerts etc. When I look back, yes!! There were definitely some callings.

One of them came when I went to my first shamanic ritual; it was just too strong in my body. I couldn’t handle myself. I had the shakes; something was happening, so I had to leave because it's too strong.

That’s why I was trying not to get close to that. Because in Korea, becoming a shaman is one of the things that you don’t want to do.

AF:

Why? Socially, you mean?

DL:

Socially, and as a job. Shamans help people and help the environment. But people now see that as disrespecting religion even though shamanism was the indigenous belief and original root of Korean culture that we all have now through music, dance, painting and culture. The shaman’s role is hard. It is like being a mother for people, a bridge between life and death, a connector or communicator between people to spirits. You have multiple roles in one body; it is powerful. That is why when people find the power in shamans, they treat them in an extreme way, either good or bad.

I remember my mom did not want me to do dance and music because she thought that I was going to be a shaman even though I did not think about shamanism at all then.

Becoming a shaman in this society that I was supposed to be part of was not a respectful job in Korea because shamanism was superstition.

If a family member becomes a shaman it could be shameful, something they’d want to hide from other people. Maybe I felt that way, too; there would be all these limitations and hardships that made me not want to become a shaman even though I had many callings. Maybe one of the reasons why I left Korea was to be free from what was in me. Because whenever I tried to do what I felt, there were so many limitations; I could not do what I thought or wanted to do in relation to the traditional forms. Even though I trained in traditional Korean music and dance, I more and more realized that I’m not a person who can keep to the traditional form. I am someone who must recreate and respond to the needs of the present moment, and include a deeper understanding of ritual and tradition too.

However, I’m grateful that I have my roots in Korean traditional art forms. That’s who I am. I have that in my blood.

AF:

It's like your skin.

DL:

Yes...it's my skin. I can feel that it’s in my skin and blood. But how am I really putting that out? That integration that I was looking for took a long time.

AF:

So you didn't find that until you had come to the United States, and by that time, you had done graduate studies in Korea?

DL:

Right, right.

AF:

What kind of work were you doing here in the States at that time?

DL:

It is ironic. I wanted to do something new, but when I came here, I taught Korean traditional music. (Laughs)

AF:

(Laughs) Of course, that's what you were trained in.

DL:

I saw it as a tool for surviving. And people who I met - all these friends who are first, 1.5 and 2nd generation Korean Americans – were thirsty about learning their culture. For me, I have to give whatever I have. That was great, and I felt so appreciative that I started in Korean traditional music and dance. It was a strong foundation for me. People encouraged me to keep doing it. They needed it, and I needed to feel that as well that I was useful in giving something so precious. That give-and-take with each other was great and so meaningful.

AF:

That's something that a community of people wanted. It wasn't so much about who you were; but it was useful to them, and you were a part of it.

DL:

Right, and it was a reminder for myself who I am, and where I am from. It was Korea imprinting itself in my body and my heart. I really appreciate that I had a long enough time to do it.

At the same time, I was playing with jazz improv musicians here in the San Francisco scene like Francis Wong, Jon Jang and Tatsu Aoki from Chicago. I played with them on Korean percussion, but I felt so much freer. I could play the way I was thinking, but it's a Korean rhythm. That was the moment that shifted my way of expression.

That kind of navigating showed me a way of finding my own project. I made a work in 2004, the PURI Project. I had a very clear vision that art should have a reason for doing it. And the first reason that I made the PURI Project was for myself, releasing my suppressed emotions, feelings and life purpose that I had buried for so long. I needed space and time to re-announce and reclaim who I am with this art. I felt that this was really important, not really being in the cave, to really go out from the fear, and understand why we’re here, and what you should do or what kind of creative process you can take to reach to the next step. I see performance as a healing process.

AF:

For yourself.

DL:

For myself. And I shared that with people. I did it as a performance. And that brought me the next level. I dealt with a lot of issues of Korean history, the Korean War, and the sexual slavery of women during the Japanese occupation, American’s involvement on Korean history through Chinese philosophy I-Ching and also the shaman’s stories and myth.

AF:

Was there someone who gave you the space to do that? How did you go from making a living teaching music, and performing avant-garde jazz to having the confidence and the space and the energy to dedicate to something that is so risky, and works in a different framework?

DL:

There were many people who helped me on getting to different places. Asian Improv Arts supported me to collaborate and experiment and develop my work Puri Project in various places. Eastside Arts Alliance in Oakland provided their spaces to present my work. Korean Youth Cultural Center and Oakland Asian Cultural Center gave me the space to give workshops and teach.

Through all this process of meeting people and places, I created a wider network of artists; I met Anna Halprin, Kronos Quartet, Pamela Z, Larry Ochs, Joan Jeanrenaud, InkBoat, Donald Swearingen, Degenerate Art Ensemble, Amara Tabor Smith and more.

AF:

I know in the beginning you were largely self-starting, but you’ve worked with Anna Halprin and she’s had a big effect on you. You’ve also mentioned David Harrington from Kronos Quartet. Especially in the last five years or so, what kind of impact have they been having on you? As you go back into that role as teacher, what is that relationship like? I’m particularly curious because I know that being a student of traditional music means a particular thing when you have relationships with other artists: it's very master-apprentice focused, and it's about passing down ways of doing things.

DL:

Totally.

AF:

I’m guessing that these relationships are different for you now. How do those work for you, how do they help you?

DL:

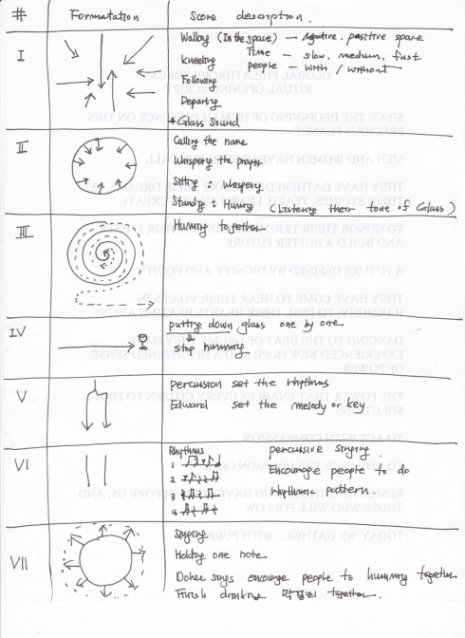

I always had a very clear idea about that part. Because traditional art is such a well-preserved formation, it has given me profound information about creating structure in performance. When you see the ritual there are various processes to initiate the ritual like a cleansing the space, prayer songs, calling the spirits, wait, receive, communicate, send, and unite people to conclude. And the other side, experiment and contemporary art, give me other information about how to add freely without limited structures. So using words, sound, drawings and writings to create potential resources as entering point to improve. Then you collect the resources/materials again from improve exploration then you can recycle (redirect) the score again. So, I combine them.

AF:

Through the traditions.

DL:

I imagine, including myself, the most important thing is what you do, is who you are. It’s not only art that you do, but also life that you live; they are equally valued and go together.

Whatever people do. Whatever job they take, they can find themselves through their actions. That's my goal. I value that people learn through traditions; that's the root, that's the foundation. Then from there, how are you integrating the foundation you know with yourself? How do those two things integrate? That’s what is most important and interesting to me.

That’s what I feel like I learned from Anna Halprin. She’s a person who doesn’t create a form, like do A to B. But she has a very clear, very scientific foundation about the body. She sees that creative activity comes out differently for everyone; everyone’s different. Each person’s expression is very authentic. My biggest influence from her is realizing that if we have very a clear and strong tradition, we must learn it very strongly and understand it. But how you really express through that, 100 percent, be who you are.

AF:

Is there a line where you feel like you would be releasing the tradition? If I knew that your traditional training involved playing certain instruments, or that there are certain forms that were required, I could easily imagine that in the work you're doing now, you could completely abandon those things. Would there still be something from the tradition remaining in the work that you're creating?

DL:

Yes. All the time.

AF:

You think so?

DL:

Yes. I studied percussion. So when I teach percussion, I’m a very mean teacher. (Laughs) Very strict. Because in order to be free, you must know the structure, really know it; then you know when to break away from the structure in general so you can improvise at a particular moment that you feel is right. But if you do not really know it, you don’t know why you break that part or participate in that part. If you start intellectually analyzing the form or structure, you lose the essence of feeling and meaning. So when I am doing it, I’m very clear. I always teach the drums, percussion, very precisely with deep listening.

And after then, okay! Let’s feel it. The rhythm that we learned, that's the part that is more self-expressive. Then it feels like you’re not a machine. But first you learn exactly what you’re supposed to play. And after that, you can change it.

So many times, you are repeating, repeating, repeating, until you kind of get bored. And then from there, okay, can you make other sounds? Freedom really comes from trust, comfortable and confident states.

AF:

You can't start from free.

DL:

No. It's really hard for me, too.

AF:

I think that's normal. But it seems like you're probably at a place now where you don’t need to go back. How much traditional performance do you imagine that you'll do going forward? Do you think it’ll still be a part of your life?

""'What is the voice that you never spoke? That you need to speak? What are the things that you never confronted?' We need to address this."" -

""My work could be political. But I don't think of myself working in that way. What I do care about is what’s happening in the land, people, the environment and also spirituality."" -