Chapter One

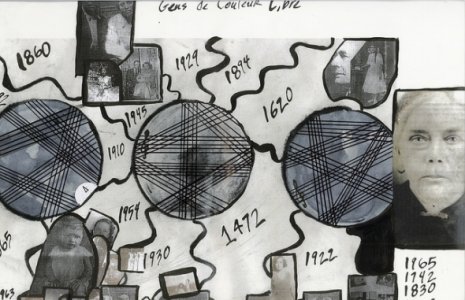

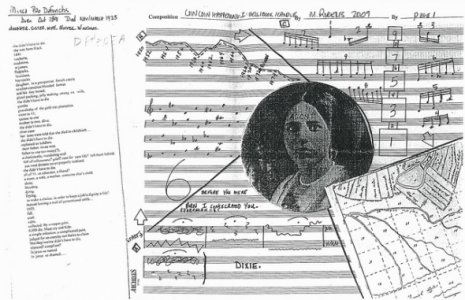

Combining structured compositions and improvised experimental soundscapes, Matana Roberts creates cross-genre pieces that draw on dance, poetry, theatre, photographs, film, oral history, and the problems of narrativity itself. Using her gift as a virtuoso alto saxophonist, and without nostalgia, she investigates the nature of emotion, freedom, political expression, the contours of her personal family history and cultural heritage. Her innovative extended post-genre work, Coin Coin, continues to be a fearless study of memory, transformation, and what remains unknown.

From her Herb Alpert Award application:

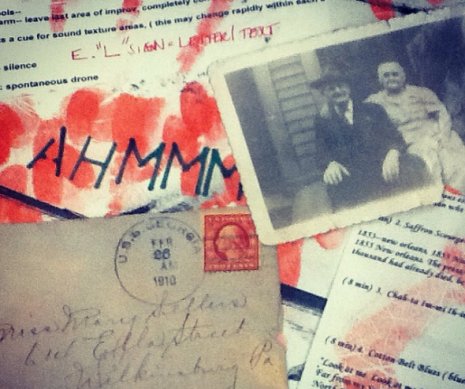

“I call the creative output of most my work up to this point, Panoramic Sound Quilting (PSQ), as an ode to my ancestral history, a siren call to my dreams, and a consideration of a constructional force that amuses, inspires, jars, and incites me.”

“…Where now is the eye that watches over the rights of humanness, kindness, witness and voice? I believe most in art that has a thick gnarled center from which far-reaching community intervention, direct action, autonomous self made culture, and global human rights accountability can be built firmly upon, and thrive. At my artistic core, I am firmly dedicated to creating a unique, and very personal, experiential body of sound work that speaks to, and reminds people of all walks of life to reach, stand up, give voice, regardless of difference, created from mere labels of intellectual classification.”

This interview was conducted by composer, musician, installation artist and 2004 Herb Alpert Award in Music recipient Miya Masaoka* via email during March and April 2014.

Miya Masaoka:

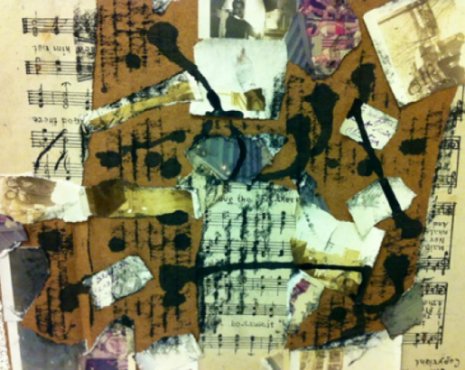

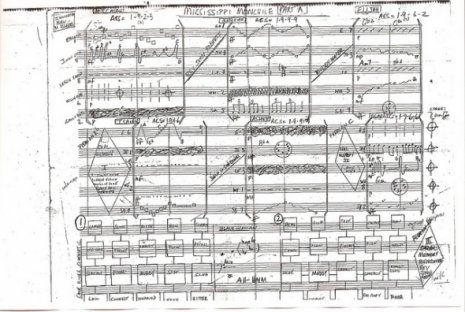

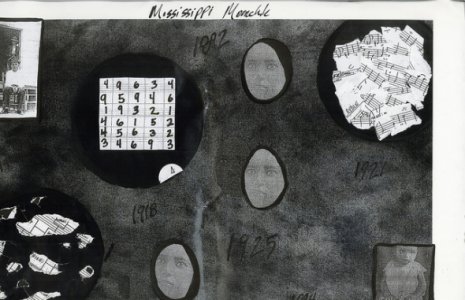

I love the graphic notation of the photo collages of yours I have seen recently, and how the grand staff is used as a trope, almost as an inset among other imagery. Can you walk us through the meaning for you, and how visual representation for aurality is generated? How are these graphics used practically?

Matana Roberts:

I'm still trying to codify a system of sorts that works for me. I'm a bit uneasy sharing much about it in detail because I’m going through a lot of changes with it at present. I can say I'm really interested in different ways of seeing, different ways of dealing with the representation of an idea or symbol. I feel that growing up in a somewhat ostentatious black radical environment where symbolism, and ideas of "code switching” carried a certain kind of weight it didn't carry elsewhere left me fascinated with how I might deal with this in sound.

MM:

That racial coding that you speak of is really interesting, as the musical score itself is a kind of code, and then the layered racial coding on top of the coding creates a certain complexity.

MR:

Presentation/the placement of things (in the graphic score) had a certain meaning that in some ways seemed so clear yet also so secret/humble/sincere. I'm trying to revise some of those ideas in a way that makes sense to me on an instinctual level, taking in full account the idea of "witness" I was surrounded by as a child.

MM:

The historical and artistic weight of the saxophone cannot be escaped, even for this interview. As a fellow traveler, who also plays a musical instrument steeped in the specificity of an historical, geographical and cultural tradition, I wonder how the notion of the fixed object of the saxophone rubs up against yourself as a living, breathing, evolving human being who is interactively and responding daily to the a rapidly changing social urban reality in New York City, 2014?

MR:

The alto saxophone is at the core of my artistic practice. It has continually taught me how to navigate ideas of creative nuance, flow, and healing and sound inspiration. The biggest problem for me as it's fixed object status, revolves more around what others seem to see when it's in my hands. I'm a musical hybrid of many different Americana traditions; there is no one simple descriptive term I can place myself under at this point. I am struggling now with where to place the saxophone's root in my overall practice because I am navigating so many sound terrains and our current societal fabric at a speed that sometimes feels obscene.

MM:

That’s a great way of putting it, this obscenity, and this sacrilege. I think of the Italian Futurists’ obsession with speed. Hundreds of years later a kind of speed seems to be the default position for our contemporary reality where we are surrounded by media and transmitted sound from a plethora of sources. At any moment of the day or night, sound over the Internet can be accessed from any place, any culture, anytime at a finger’s touch. It can flatten out the experience of received listening – or how the audience perceives their experience -- but also be invigorating. Sometimes the artists’ relationship to their instrument, or a particular way of working, evolves, but the public may be reluctant to evolve with them. I’m thinking of Bob Dylan when he went electric and left the more folk music scene and his fans were angry and confused. It can be like that for musicians associated with a particular instrument.

The socially complex act of working with ensembles and collaborating with others to collectively create something can be fraught with pitfalls, or can be a potentially ecstatic experience. This is so different than what a painter has to do, or even what one does as a solo artist. Does this process of working with others come easily for you? What are the principal challenges?

MR:

I do my best to go with the flow of a given situation. That’s one of the most powerful lessons that improvisatory traditions have taught me. There is never a wrong note/ musical structure in an improvisation; it’s all about placement and, in some sense, partial resolution of an idea that can be used with some flexibility when confronted with creativity challenges, whether alone or in a group.

MM:

On Mississippi Moonchile (2013); Gens de Couleur Libre (2011); Live in London (2010), there are some interesting compositional strategies. Can you describe the recording process and your approach?

MR:

Those are all very different records that required different approaches. Two of those records were recorded with live witness, and that's something I really like doing because that sense of connection is important to me. I see part of my role in creating sound is as a healer, and being able to heal in real time gives my life much purpose. The Live in London music was recorded in a club while Gens de Couleur Libre; we fit 40 people in the studio with the 13-piece band, so it created a different emotional space for all involved. Gens de Couleur Libre was recorded 10 days after my mother died so my approach in terms of the healing aspect was also directed towards me as well in terms of performing/sharing that work. The Coin Coin music is very much dependent on the live witness aspect I have found, so with that series that will most likely always be an important element.

Live in London, and also the Chicago Project that I did for Barry Adamson's CCI records, are much more straightforward and established in a certain terrain of improvisatory thought. Gens de Couleur Libre and Mississippi Moonchile are part of a large series that purposely encompasses all of the things I feel I couldn't do in the improvisatory terrain I explore on the CCI records. I created that space so that again the idea of "boundaries" or "restriction" would not apply in my art world. Also, I'm a huge American history buff and I was looking for a way in my work that would allow me to explore this history from a viewpoint that brought in elements of the personal in a very ephemeral way.

I use the term witness or "witness participant" or some version thereof, as a way to avoid the word "audience," which to me translates as a distinct and disconnected voyeur/performer relationship. I'm more interested in ways I can use experimental performance and experimental sound to create a collaborative giving experience between what is usually seen as giver versus receiver. I see making my music as a way to create one large spontaneous organism that moves as one and not as separate entities dependent on separate roles. In my ideal sound world there is no such thing.

*Miya Masaoka is a classically trained composer, musician, installation artist residing in New York City. She has created works for the response of plants, the movement of insects, as well as multi - channel sound installations using spectral distribution of tones, as well as designing responsive wearable computer textiles. She also writes for ensembles and her work was recently read by the La Jolla Symphony.

Curriculum Vitae (PDF)