Belief Theory

GV:

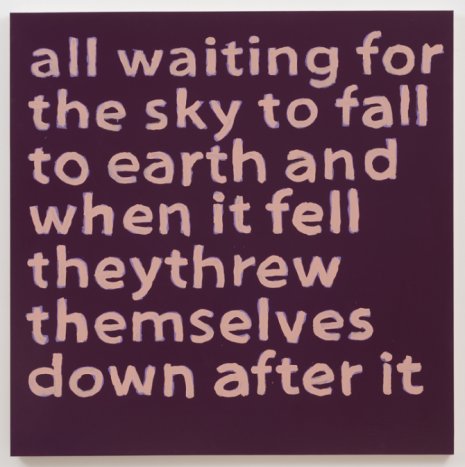

This brings me to a project you and I developed for the Cairo Biennial in 2006, titled Call Me Ishmael, The Fully Enlightened Earth Radiates Disaster Triumphant. As I remember it, the project was inspired by the dystopian science fiction classic Blade Runner (1982), set, not surprisingly, in Los Angeles. There is that fantastic scene where Daryl Hannah’s replicant character gets shot by Harrison Ford which causes her body to short circuit and convulse uncontrollably. Your concept was to cast yourself in animatronic form, endlessly looping between stillness and uncontrollable seizures. In a sense, it was performing a self-portrait and the second in a trilogy of animatronic self-portraits.

DJM:

I think this may have to do with my lifelong relationship with Disneyland and the really extraordinary influence it had over me when I was young and, in many ways, still does. When I was very young I remember seeing for the first time Abraham Lincoln sitting in a chair and then stand up and give the Gettysburg address. I was mesmerized. I thought they had made him come back to life, and I just sat there watching him repeat the speech over and over again. Then it was on to see the Pirates of the Caribbean, ho-ho-ho ‘a pirates life for me, and, hook, line, and sinker, I was convinced this was the future. I have had a long-standing interest in cyborgs, clones, biomechanical androids, machine life, and the possibility of a new future model of human beings where technology and human consciousness could be combined to create a new form of human/machine. I wondered: what would the future hold for the new human body?

The challenge was to figure out how to utilize the idea of performance, self-portraiture, and build an animatronic that was advanced as possible with the smallest amount of resources. My goal was to have it become something that had the possibility of transcending the lifeless machine to become something beyond a mere human or machine. Ideally it would be something so Other, so unsettling that you couldn’t erase it from your mind once you experienced it. History and a series of seminal texts were very important starting points; this included the work of Philip K. Dick; Alan Turing, the 18th century chess-playing automaton known as the Turk, Edison's Eve: A Magical History of the Quest for Mechanical Life by Gaby Wood; Darwin Among the Machines by George B. Dyson; Donna J. Haraway’s essay, The Cyborg Manifesto; The War of Desire and Technology by Rosanne Stone; The War in the Age of Intelligent Machines by Manuel de Landa; and The Melancholy Android by Eric G. Wilson.

These writers had already laid the foundation to a complex and critical environment in order to understand what Disney was doing when he opened the original Disneyland in Anaheim, California and how Ridley Scott, via Philip K. Dick, developed the replicant characters in Blade Runner. Terminator, Battle Star Galactica, and countless other films and writers created new propositions for sentient cybernetic life in the 21st century.

As you suggested, the idea began with the desire to create a trilogy of machines, three different clones, doppelgängers of myself to enact, and effectively take the place of human performers, but to be more human, more performative, more nuanced and emotive than any ordinary human could accomplish. These new selves would go beyond the traditional behavioral or performative act to establish a new trajectory or entry point. To reexamine the origin of time and dimension where the politics of human representation are challenged and interrogated. To make explicit all its accomplishments and crimes as only ordinary humans are capable. A species whose existence is defined by death, genocide and the atrocities perpetrated upon itself in an endless cycle of destruction.

The first animatronic performance piece I made was based on the life of one of the greatest writers in Japanese history, Yukio Mishima, who performed ritual suicide on his 40th birthday. This work is titled; To make a blind man murder for the things he’s seen (happiness is over-rated), 2002. The attempt here was to write the program of my clone to do the same thing, to commit suicide over and over again, endlessly experiencing the horror of slitting one’s own wrists. This is similar to the myth of Sisyphus, and the book of the same title by Albert Camus, as well as the story of Prometheus. I placed my robotic doppelgänger, a lone figure dressed in blue workers overalls, in an all-white room - think 2001: A Space Odyssey – on its knees facing the far corner of the room. It is looking up and down laughing out loud like a prisoner in an asylum with a razor blade in each hand, with each hand, in turn, striking each wrist. Then something happens where the machine has an existential crisis on its own accord, and stops mid-way through the act of killing itself; it’s as if it gains its own form of consciousness and cannot fulfill its own programming code to commit suicide. The machine starts to laugh like a madman as it struggles between organic desire and its need to fulfill its programmed function. This gesture becomes overwhelming yet at the same time as calm and intimate as the breath passing between lovers.

The second event for performance was the piece for the United States Pavilion at the Cairo Biennial in 2006. By this time, many years had passed and I had become clearer in creating experiments of machine life. As with Mary Shelly in Frankenstein, the second attempt succeeds where the first failed. The doppelganger became more ambitious in the attempt to reject the program and rewrite the code to its own desires. In other words the machine takes over the code to recreate a new representation of human nature gone completely out of control. I turned to the three institutionalized religions where the name Ishmael appears as a central figure in all three stories: the Old Testament in the Book of Genesis, the Qur’an, and the New Testament. The name appears in the first line of Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, so I titled the work, Call me Ishmael, the fully enlightened earth radiates disaster triumphant. The attempt was to create a performance where the figure utterly destroys its own body by triggering a form of epilepsy that forces the body to repeatedly bang and slam its hands, feet and head as hard as possible in order to lose consciousness. One could imagine my doppelgänger could break every bone in its body until it hemorrhaged internally and died. It was like an attempt to knock oneself unconscious and get locked in a loop reminiscent of being beaten to death, with clubs and batons, or stoned with rocks. This time the figure performs on top of a platform to allow it to operate like a drum, so the sounds of its fists, feet and head hitting the floor would create an echo and become louder and louder. The sound of "my" death becomes deafening to the point of torment to the viewer. I imagined it to be similar to having to watch and listen to actual tortures perpetrated upon human by humans. Here though, the machine cannot reach the pit of program defiance, it seems only to be capable of endlessly repeating its cycle of self-flagellation over and over.

Simultaneously, it was an attempt to replicate the physical movements of Pris, the nexus 6 replicant, in Blade Runner when she is shot. In her final scene she goes into convulsions after her wires begin to short circuit and her quest for humanity dies along with her. Pris, like the other nexus 6, only wanted to live a life filled with love and not be a slave to war and colonization. Another similarity is to Data on Star Trek, which strives to become more than the sum of his programming, to be a machine that desires to become more human. Imagine if one of these characters actually succeeded in being the most advanced self-reliant intelligent sentient machine that could embody the most admirable qualities of being human – ethics, morality, and compassion – and most importantly to be able to love and be loved. Isn’t that what we all desire? The third and final performance will be based on a painting of Goya and the inquisition and will be the final examination of our death, the death of the human species.

GV:

Let’s talk about a recent project that focuses on something you mentioned earlier regarding the three institutionalized religions, Christianity, Islam, and Judaism. The piece from 2010-12 is titled, A Story for Tomorrow in 4 Chapters, Dostoevsky Loved the Hunchback of Notre Dame, Muhammad Ali and Dandelions, Lick My Hunch! For me it encapsulates so much of what your artistic practice is comprised of: photography, text, literature, examinations of power, and the political roots of violence. Most importantly though I feel it communicates a very powerful statement on the nature of artistic practice at this historical moment. In other words, if we do away with the current spectacle of the art fair, the diminishing power of museums, and the ridiculousness of the contemporary art market, what are we left with and where does the truly visionary and radical platform lie for the contemporary artist?

DJM:

Your question is an important and extremely urgent one. It is very difficult to navigate the minefield you have laid out here. I don’t have an answer per se, but a number of structural changes have made it perfectly clear as to why the current climate seems so compromised. One is simply that we cannot use profit, popularity, or an inflated market as a means to determine the value of art and ideas. Secondly, we need to identify and examine the current status of artists, which, in my opinion, is last in the hierarchy of power. There was a time when artists led the field with their work and ideas. Gallerists, curators, collectors, critics, museums, magazines, journals, and all the other components who constitute the field of art looked to the artist to lead the field, not be last in line, as is the case now in the current collector and market driven orgy.

But then again who cares? I wonder if we took a cue from the black militant group in the 70s called UAW/MF (Up Against the Wall Motherfucker), and attacked the core of the cultural industrial complex in the same manner we would if it was the military or a corporate entity. But I am not sure that’s where anyone wants to spend his or her energy. Focusing on a type of practice that is both complicit, and that critically interrogates the field we are in, seems a sustainable, pliable strategy that can employ 21st century tactics to accomplish something that goes well beyond the current rule of Caligula and the orgy of wealth and its shallowness. Or perhaps we need to re-evaluate the ethics and principles into what our present ideology about artists and the making of contemporary art are? How can this point us toward an impossible improbable, an unknown future led by artists that resides right below the thin social veneer that tethers our world together?

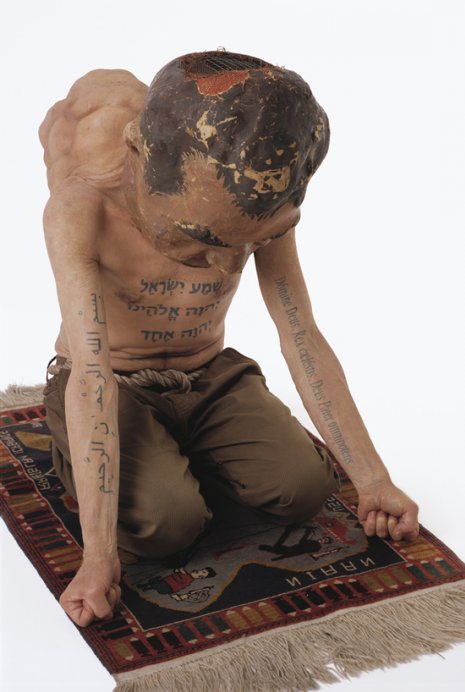

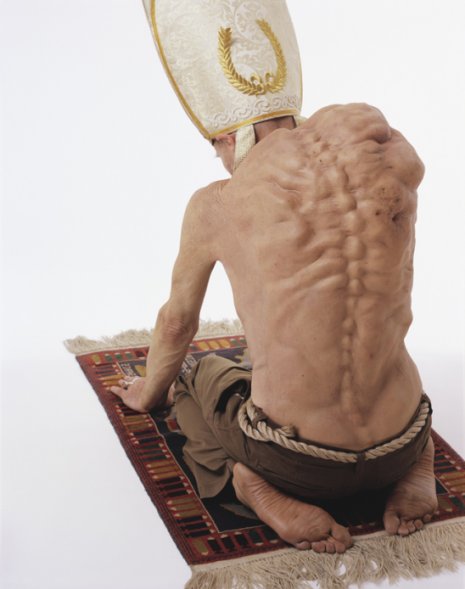

As for the work you are referring to, it’s an interesting choice since the piece resumes a different trajectory from the animatronic works where I am seeking the biomechanical future. Now, with these performances, I turn back to the organic, the corporeal shell of the human. I am still looking for new ways to compress the forms of sculpture, performance, photography and the dominance of the deformed body into a single form. These works challenge and combine the three dominate religions - Judaism, Islam, and Christianity - by taking the most holy of texts found in all three religions and “tattooing” them directly onto my body, which has adopted and shape shifted social and mental deformities projected onto my body in the form of the misshapen hunch. The fundamental inspiration for my piece is the original film, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, in which the central character, a tragic figure, uses the church as a site for political asylum. The hunchback is a bold grotesque embodiment of both strength and weakness. A frail, pathetic image of a male body is exposed for all to see and to bear witness to its inevitable collapse. In evolutionary Darwinism this body would not survive in any environment, or, at best, live a life of suffering with no other purpose than sheer existence itself. What does that serve in the end? The struggle and debate over who lives and dies in the name of which god, and if there is even a god to debate, represents thousands of years of wars, cruelty, genocide, murder and torture. A story for tomorrow in four chapters is a passion play, a critically focused lens set upon our frail and misshapen humanity. I wonder if there is a god, and if he exists, will he ever forgive us for what we have done to each other?

GV:

The companion piece to this photographic series is a sound and sculpture construction from 2012 entitled, It rains on the just and the unjust at the same time. Viewing it together with A story for tomorrow creates an interesting counterpoint to the graphic juxtapositions in the photo-performances. It elicits an incredible emotional sensation that is unlike anything I have experienced in your work up to this point. Can you describe the source of the music that emanates from that piece?

DJM:

I was thinking that perhaps Call Me Ishmael is the mirror image of the performances in A Story for Tomorrow in 4 Chapters, Dostoevsky Loved the Hunchback of Notre Dame, Muhammad Ali and Dandelions, Lick My Hunch!, through the events of history; and an attempt to draw a map of our unconscious minds through external behavior. Somewhere in here lies the persistent reality of our daily battles. Who we are and what we desire to be is the age of war and technology. Constantly interrogating the nature of our unstable human existence.

I don’t think I ever told you about the story behind the sound sculpture. It actually began when we were in Cairo working on the biennial. I was in a tiny cab traveling through the city, not exactly sure where I was going. The cab driver had a cassette tape playing of a man singing this intoxicating music. We were in traffic so I listened to most of it. When I tried to ask him who the singer was so I could get the tape, he popped the cassette out and gave it to me. Not sure how that happened since we couldn’t communicate at all, no English, no Arabic. It turns out that the singer was a famous Egyptian performer from the 1950’s with a dreamlike, emotive voice. But the sound changes instantly once it is played on a cassette player and then amplified by a bull horn hung from the wall by a clear acrylic rod, which is the way I display it. The effect is drastic. It sounds like a call to prayer being played over the city in the dawn’s morning light, or like a mist or light fog drifting everywhere, emanating from the top of the minarets of the mosque. I can so clearly both see and hear that sound every morning and throughout the day, but it was in the early morning that it seemed the most seductive. What was once secular music has now become part of a religious ritual and, even more importantly, become political. So when one is looking at the photos it’s a moment of pure intoxicating poetic sounds that make you hallucinate, and at that moment you realize that the world is just another kind of asylum and that everything is political. Everything, no exceptions.