In Bani's Words...

My dad bought a video camera on my sixth birthday to document everything we were doing in our new home in the United States for the family back in Iran. Today these images serve as a sort of past archive of immigration and transition for me with regards to my family and my birth country, something I have decided to revisit, and possibly work with while exploring ideas around transmission within my new role as a mother of a 5 year-old.

I myself began making images first with this video camera at the age of eight, and then later on in a more intentioned way while in high school in Texas.

It was at this time that I first felt the strong desire, and what would later become an urgency for me, to become an artist. Although my parents were eventually supportive of me, they were opposed to the idea of me becoming an artist or a filmmaker, convinced that I would lead a life of struggle. But the drive and vital need for me to speak and express myself through a visual medium could obviously not be stopped. After starting architecture school at the University of Texas at Austin in 1999, I secretly switched over to the film school after just one semester. Going to screenings every night on campus and frequenting events put on by the Austin Film Society, I completely fell in love with this world. I discovered auteur cinema, but also ethnographic, avant-garde and essay films, which would become my background and foundation. I was very fortunate to be in Austin at that time, just before the gentrification sparked by the start-up industry would completely kill Austin’s “weirdness.” We lived a time of complete freedom, risk and collective action that allowed not only many filmmakers and artists to create community there, but to explore form and content within a heightened creative environment.

When I graduated in 1999, exactly twenty years after having left Tehran at the height of the revolution, I made my first trip back to Iran hoping to make a first film there. I was very excited but also terrified of how I would fit in, not to mention the context of the dictatorship. My idea was to make something about diaspora and the immigrant experience, but that changed after just a month in the country. It was much more urgent for me to explore our history and the political situation there, the censorship and how people were resisting the regime. Also, there was something primeval about my new connection to the country, while my parents had never returned during all those years. I spoke Farsi, which allowed me to get closer to people while I probed my own memory and senses. I was using observational and direct cinema methods, roaming with a handheld camera in public space.

My first documentary, A PEOPLE IN THE SHADOWS, filmed during the winter of 2007, is literally me walking around Tehran, observing daily life and talking to people about U.S. sanctions. My goal was to break the silence and the ostracization of Iranian people even if this was a complicated task. Getting permits to film and finding people unafraid to talk was a challenge but one that somehow allowed me to become a part of that place again.

Two years later, I returned to Tehran to film during the 2009 election. What started as another direct cinema project, observing a fervent debate culture on the streets, eventually led to my participation in the biggest revolt since the 1979 Revolution. That experience changed everything for me, including the way I work. I continued to be an active agent in what I was filming, but began thinking more critically about my own role as an image-maker.

While protesting, camera in-hand, I kept thinking about the archival images I grew up with, and how these had formed my own ideas of what happened in 1979.

It was the first time I worked with archives, something I had started exploring the year before the elections, when I was at the Whitney ISP in 2008. With my images, that I smuggled out of the country, I decided not to make a straightforward documentary chronicling those days, but an essay film to reflect on our political history, as well as installation work deconstructing the archive of our revolutionary past. I think that this is really when I found my voice, at least in the documentary and essay format.

How can our broken existences and stories make us stronger as a collective body? What drew me to this was an uncomfortable silence that exists in my family as in many others. My mother’s cousin was taken as a political prisoner in 1988 and never returned. With no news of her whereabouts, we are left with this void, yet we are not alone as thousands of families lived the same situation.

My work in fiction is quite different. I’m interested in creating intimacy through observational storytelling. I want my films to work on a visceral level as well, so I dedicate a lot of time to pacing and sound design. Through fiction I have often explored themes related to exile and migration. Around 2002, I was doing activism in France with a collective that problematized the legal frameworks that allowed for the neglect and oppression of migrants’ rights. I regularly visited the camps in Calais and collected testimonies from exiles, mostly from Afghanistan, Iran and Kurdistan. This was the genesis of what became my first short film, TRANSIT, inspired by their stories.

My last fiction feature, FIREFLIES also started from testimonies. I traveled to Istanbul to meet Iranian LGBTQ asylum seekers in 2014. Inspired by a true story of an Iraqi migrant accidently arriving to Veracruz, Mexico in a cargo boat, I decided to adapt a different context that could reflect once again on the situation in Iran. FIREFLIES is about a gay Iranian man who accidentally ends up in Veracruz after fleeing Iran and crossing Turkey. I wanted to talk about the state of exile and the similarities within the experience of displacement, as the main character meets others suspended in this place. The film is also about place and the body, an attempt against the invisibility of LGBTQ Iranians in cinema.

Since at the moment I cannot travel back to Iran, it is important for me to think even more determinedly about what work I am making as well as what I am passing on to my daughter; our language and culture, but also the family’s story. Images filmed by my father and grandfather mingle with 15 years of footage I have filmed while traveling back to Iran; all tied together with current moments, small gestures, reflecting on past and future through the present instant.

I am also working on two feature films, both of them in the advanced writing phases. Since becoming a mother, my goals and creative desires, as well as the ethics around my way of working have become more pronounced and clear. Despite my love of Iran, I consider myself a transnational artist, since I find commonalities and inspiration in other contexts as well. In 2012, I married a Mexican man and began to explore similar themes in his country, somehow my adoptive country. The parallels are astonishing sometimes, and although language and the specificity of history are important, I realize that many of the themes that move me can be explored anywhere. I have made a clear decision to make work through a long, investigative process that not only takes me to documents and archives, but through philosophy and memory work. I am concerned with past violence and reparations for the disappeared.

In my past work I have not really been interested in identity issues or our experience as immigrants to the U.S., probably because our assimilation went very smoothly.

Within the capitalist context and an ever-growing discourse of violence and individuality, this is the real threat that I feel, not the conflation of personal growth and transformation as if it has an impact on the collective experience.

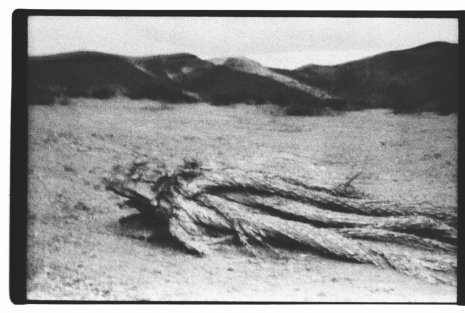

My current focus is on the atrocities that have marked us collectively, whether in the context of immigration or political purges. My interest in this probably originates from the disappeared member of my own family and the unmarked mass grave where she may or may not have been placed. Unable to approach the question within the context of Iran, I have began to reflect on this in an expanded way. At the heart of my exploration is how we have kept silent about this for so long out of fear of repercussions. The earth, the land, this “homeland” sustain our silence while being the main witnesses to those atrocities.

Whether doing documentary, fiction or installations, I've spent a lot of time working through my embedded feelings and my sensorial connection to the past while thinking about a global and historical experience of exile and migration. Whether it be in Texas, Sicily, Eastern Europe or Mexico, I have found that the history of migrations are repetitive and an essential part of humanity’s story.

I am currently showing an exhibit at the Museo Experimental El Eco in Mexico City called “El Chinero, un cerro fantasma” (a phantom mountain), about a site in the desert of Mexicali where a group of Chinese migrants died in the early 1900s. I am studying the landscape but also the documents from that time, reflecting on the idea of the archive, its authorship and omissions. Using black and white photography and hand-developed 16mm film in a loop, the installation also incorporates drawings that I made, objects found at the site and some archival images and documents that point to an atrocity and the disappearance of a group (or many groups) of anonymous people within a heightened moment of nationalist discourse and growing racist campaigns.

Through my work I seek to breach the divide between national narratives and reinforce ideas around our shared stories, in a world that seeks to put us against each other. Living this nomadic life, creating across borders has been a big part of me, but now that I am a full-time mother I have had to make big decisions about what I work on and where. Traveling is not as easy as before, so I constantly rethink the way I plan my projects. This has pushed me to organize my time and energies in a way where I can be at home with my family while preparing projects through slower, more detailed process.

Displacement has always framed my life and influences how I conceive of things, but I realize that for my daughter there is no similar past. I work through these issues that continue to move me and reflect on what heritage and memory mean now that I am a mother. In the context of Iran, as is the case with so many places living under authoritarianism, it is also important for me to think about what it is that threatens our memory work.