In American's Words...

I make what have been described as “thought experiments” using the media of sculpture, video, and digital art. I’ve been an artist my entire life, but these are the mediums that have inspired me most recently. I don’t think of “political art” as a genre. The truth is, I think all art is political, but not all art is critical. Most art upholds the compromising systems of the world by folding into them. I try to disturb that within my work.

Many of my works are digital in nature, challenging the limits of what an institution is or what it can represent. The most successful example of this is Looted (2020). During the height of the protests in response to the murder of George Floyd by police, many institutions in New York and across the nation were boarded up in anticipation of something happening. I began to think about what it means for a museum to protect its contents from the people, given the history of museums and their relationship to looted materials. For the intervention which took place online, I removed all of the images of art on the Whitney Museum’s website and replaced them with images of plywood boards. The question I posed to museums more broadly, more so than the Whitney specifically, is whether they really own the artifacts they claim.

Much of my work over the past several years has been inspired by Black Studies, drawing on authors such as Simone Browne, Christina Sharpe, and Fred Moten to name a few. I have used these authors to consider police violence, surveillance, and technology and to question these things through my art. In 2019 I debuted two large scale exhibitions addressing policing. I’m Blue (If I Was █████ I Would Die), was an indictment of police officers to call out their use of the color blue in the Blue Lives Matter movement. The second exhibition, My Blue Window, was a somber portrait of the NYPD’s use of predictive technology to determine criminal behavior. While both exhibitions were effective in challenging these issues, as someone affected by them, the process of engaging was psychologically difficult for me, and I felt burnt out at the end of the year. I’d like to focus on work that is “life-affirming,” taking note from the abolitionist Mariame Kaba. Rather than focusing on the violent ineptitude of law enforcement, I choose to imagine the world I want to live in and how to make that a reality.

This framing of my work has involved taking a critical lens to history, migration, family, ancestry, and what inspires me creatively deep in my soul. Many of my works are what I call “speculative artifacts” that resemble devices, tools, or video evidence of real world events but are clever fictions, subtly posing questions such as “is this real?,” and “what year are we in?” I use this strategy, which Saidiya Hartman calls “critical fabulation,” to spin my own narratives that expose the truth of history and are wilder than fiction.

This shift began with my current body of work titled Shaper of God, which is inspired by the late science-fiction author Octavia E. Butler’s life and her relationship to the suburb of Los Angeles that she grew up in, which happens to be my hometown. Following in Butler’s footsteps, I am a student of history, quietly observing and making connections across time. Because the topics I have studied such as political turmoil, segregation and policing, and the perils of new technologies are key figures in Butler’s novels, this has allowed me to approach the same subjects from a different perspective while also bringing visibility to Butler’s life and work, which gained popularity during the pandemic of 2020 that her novels narrowly predicted.

I am in the process of getting funding for the next stage of the project. This will be a critique of private space travel financed by billionaires, while also engaging Butler’s inherent curiosity with space travel and her question of what a non-colonial interest in rocket science would look like. I am planning to create a live event that reproduces rocket tests performed in Pasadena, CA in 1936, as if a similar test is being performed 100 years later by the protagonists of Butler’s California Dystopic novel Parable of the Sower. This will bring the future and past together while also centering a Black and anti-colonial perspective on rocket science.

My mom, my sister, my dad’s sister, and mother were all teachers in elementary schools. I come from a family of teachers, all Black women in California, either born in Tennessee or descended from Oklahoma. Their M.O. was “keep your head down, work hard and have good manners.” I do that for the most part, but my curiosity has led me to be oblique when it comes to my politics; too much harm is done in silence to not say something. I understand where they’re coming from, for the generations before me it was mortally dangerous to speak your mind. But because of them I am in a position to point out what’s not right, and question why things aren’t changing. I’m the first in my family to have a master’s degree so I’m no stranger to navigating spaces I was never meant to occupy. This is no different with my job now, as a full-time professor in an Ivy League university. I find art to be a powerful and evocative means to speak and educate, and, in that sense, I find synchronicity with these women.

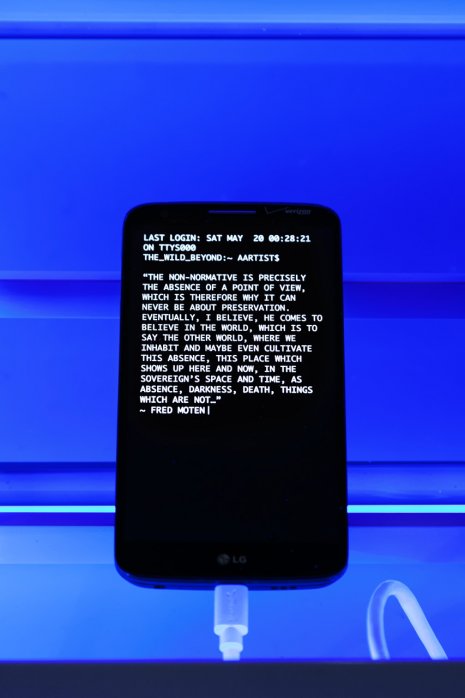

In 2017 during my residency in the Whitney Independent Study Program, I was looking to merge my interest in Black Marxism with digital systems. As I peered into the history of the computer work station, I learned of the shift in the early 1970s from a black-screened command-line-interface to a white-screened Graphical User Interface. This transition, which was promoted commercially with “a black screen is bad for your eyes” felt representative of a kind of chromatic erasure occurring socially that was heightened within computation. An interface where whiteness was a “neutral” backdrop that mirrored the corporate office space became dominant. This initiated my body of work Black Gooey Universe. Drawing on the concerns of Afro-pessimism, I’m seeking to ideate a computer that is resolutely Black. What would that mean? After researching the colonial history of California’s Silicon Valley, I wanted to understand what values had been cast aside in the pursuit of an all-white office space. I quickly learned about the transition of the computer screen from black to white. My mind ran wild with associations. “Machines have the morality of their inventors,” wrote Amiri Baraka in 1970.

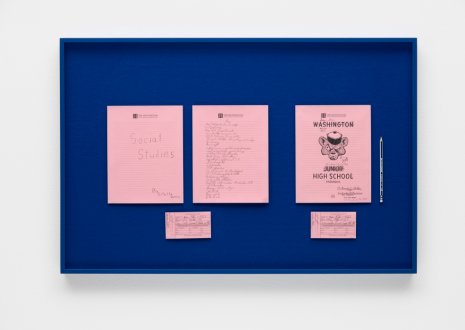

The first piece in this series is The Black Critique (Towards the Wild Beyond) (2017). Prior to that I was not making sculpture. A funny thing happened within the Independent Study Program, a program which is historically a documentary-film oriented group of artists. I knew there would be lots of video in our end-of-year exhibition so I opted to make something physical. This was my first time making a sculpture and after that I fell in love with sculpture.

It is no surprise that the latest machines have racial biases. The sculptures in this series are attempts to bring forth qualities such as slowness, brokenness, stickiness, softness, loudness—everything that we don’t want in a computer—to consider what computation would be, if a different group of people had been part of those early conversations. The sculpture Mother of All Demos (2021) refers to the first demonstration of a clickable interface, but it is a computer made of dirt, and covered in black asphalt, unsavory to the touch, but obviously in use, and useable.

As my work progresses, I want to continue challenging the legacies we inherit from history through sculpture, video, and digital intervention. And to encourage those who engage with my work to remain critical of the social conditions that they take for granted. I want to aid them in imagining—as it is described by Jack Halberstam in the intro to The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study, by Stefano Harney and Fred Moten —“a wild beyond to the structures we inhabit and that inhabit us.”