About Nora Chipaumire

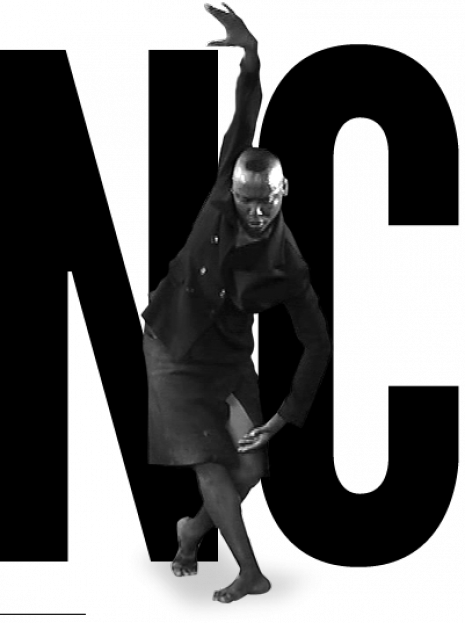

Choreographer Nora Chipaumire tackles subjects at once global and personal, attempting, as she puts it, “to express a poetic insolence that rebels against ignorance, honors ownership of the body and imagination, and conveys freedom and strength.”

A charismatic performer described as having a “towering, incandescent presence,” she began her formal dance training when she emigrated from Zimbabwe in 2000. After dancing with multiple companies including Urban Bush Women, Chipaumire began choreographing solos for herself, making dances as resistance, as self-affirmation, as refuge and survival, her solo voice signaling the most private and intimate of conversations.

I became a dancer in the USA; I choose to embark on a life of self-exile from my country of origin, as well as expectations from my culture, and my family. I chose dance as a language to address my demons, my past, and my dreams within this context of self-exile. This state is intrinsic to my aesthetic, the subject matter, and the dissemination of the work.

When I first took my modern class in Oakland, California, everything came into perspective for me. Through dance I could really create my own language and tell my own stories. I was so very much moved and convinced by people like Martha Graham and Doris Humphrey, Isadora Duncan, and Mary Wigman…powerful women who were able to break from the ballet tradition to tell their own personal stories and use their own vocabularies.

…that’s what’s still exciting to me about modern dance or contemporary dance: you have this freedom to break from tradition, to break from whatever is the canon and find your own way and find your own voice. From NPR interview

Chipaumire’s work grapples with issues of struggle, determination, oppression, and loss, work that examines how values about democracy and religion are palpable in precise deployments of time, space, and force.

From 2000-2010, I made dances that I saw as fados: dances of deep sorrow and physical poetry set to music, dances full of longing, noble suffering and memory of injustices from another time and place. My dances have become less about grief and displacement, as I have become more aware of accepting responsibility for creating work that inspires a world without poverty of the spirit and mind…

What’s the shame in just dancing? Why does it have to be so abstract and obtuse that nobody gets the point…? I’m trying to lose some of that. You train in some school for contemporary dance and it just gets so heady and abstract. I’m trying to regain the emotional power, the sheer visceral and physical power that connects one human being to another. From an interview by Zachary Whittenburg, in Flavorwire, October 2, 2009

Chipaumire examines what a womanist body might be. Does a woman become more powerful if she emphasizes her masculine side? Is she taken more seriously downplaying her femininity? Going beyond issues of gender and race, she raises questions about power that are meant to cause confusion and inspire dialogue.

Ancient, tribal, ethnic, colonial, modern, and post-modern cultures live in my body; each dance is an attempt towards self-determination within that loaded landscape as I physically resist and accept my complex personal and collective history.

My work as a dance maker has been largely about radicalizing the way the African body and art making is viewed at home and abroad. I am devoted to shifting the central point of view of Africa as being solely the holder of past traditions and forms, and not a place of the avant-garde or innovators. [AAIA application]

Chipaumire engages in sustained research in the creation of work. Her “Dark Swan,” a re-thinking of “The Dying Swan,” Michel Fokine’s choreography for Anna Pavlova, grew out of looking at images of fleeing Darfurian women and children, and at sources as diverse as Picasso’s “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon,” and Zimbabwean writer Dambudzo Marechera’s novella, “House of Hunger.”

Throughout her years of making solo dances, Chipaumire has drawn upon the perspective and talents of artists across disciplines. She joined with famed exiled musician Thomas Mapfumo, “the Lion of Zimbabwe,” to create the multi-media performance, lions will roar, swans will fly, angels will wrestle heaven, rains will break… Now she is completing, “Miriam,” her first character-driven dance theatre work with composer and pianist Omar Sosa.

My work as a dance maker has been largely about radicalizing the way the African body and art making is viewed at home and abroad.