About Michael Smith

Artist Michael Smith, who began his career as an abstract painter, performs, makes videos, sculpture and drawings, creates multi-media installations and puppet shows, and does stand-up comedy. He pioneered reality television shows before reality TV existed. Hovering on the edge between art and entertainment, the sociopolitical and the aesthetic, his serious, satiric, poetic work has been seen on commercial and cable television, in comedy clubs as well as in museums, galleries and at Burning Man. Inhabiting the personae of the naïve, baffled, inept ‘Mike,’ a hapless Everyman, (think Willy Loman and Candide with slow timing and delivery), and ‘Baby Ikki,’ a pre-linguistic, genderless infant, Smith grapples with the real world of global trade, nuclear war, colonialism, real estate, and simulacra.

For all the ‘loneliness’ of his persona, ‘Mike,’ collaboration figures strongly in Michael Smith’s work; his compañeros have ranged from Joshua White to Eric Fischl to Mike Kelley. He cites Buster Keaton, Vito Acconci, Richard Foreman, Samuel Beckett and William Wegman as influential in his exploration of formal structures and existential humor.

Ingrid Schaffner, Senior Curator at the Institute of Contemporary Art, University of Pennsylvania, interviewed Michael Smith via email, March 2012.

I was a baby boomer raised in a middle class Jewish family on the south side of Chicago. Like so many of my generation I grew up in material comfort with a sense of entitlement. Only much later did I become aware of the discrepancy between what I learned in school and saw on TV with what I saw around me at home. My acceptance to Colorado College - helped along by my brother being an alumnus - was contingent on entering a special summer program to give me a running start before fall classes began. I took this trial period very seriously and dorm life and new friends took a back seat to grades. It was the late Sixties and drugs, music, looking inward and rebellion was happening all around me.

From my perspective most of the student body at Colorado College was blond and much more familiar with prep school codes than I was. It was not difficult to feel different there. I moved in with my older brother, Howard, a serious, committed abstract painter, and living with him proved to be a major game changer for me. I enrolled in a drawing class he was teaching at another school and he soon became a mentor to me. I got special attention and lots of encouragement and, before I knew it, I was a serious artist too, (very precocious, to say the least,) and accepted to the Whitney Museum Independent Study Program in 1970. I was by far the youngest participant and since I was only 19, for better or worse, this reinforced a feeling of entitlement, commitment and passion for formal, abstract painting.

In 1973 I returned to the Whitney Program, convinced today that my acceptance back then was because of my love for sweeping and I could be counted on to keep common areas looking clean. The big changes during my second stint at the Whitney program were changing out of my painting clothes when leaving the studio and trying to rebuild my social life. It became more and more difficult to maintain the serious and earnest posture I initially thought was needed to be a true artist. The change of attitude coupled with a dead end path I was headed on with my painting made the transition to a post studio practice seamless. Chicago proved to be the perfect place to change. It was inexpensive, familiar, friendly, and offered the perfect amount of distraction and culture to find myself and locate a new direction.

To call me a pioneer is an exaggeration. There was a lot of performance activity going on when I first started in the early to mid-seventies. It was the thing to do and also intersected with my new interest in being social. I could go to events, convince myself I was working or doing fieldwork and meet people all at the same time. It’s important to remember that the alternative scene was the main outlet and social network for young artists, and Chicago was a great place for me to develop, but I always knew that I would eventually move to NYC.

Many of my New York friends were totally caught up in loft madness and needed a loft to make their work while reinforcing their identities as artists. Moving from painting to performance, not needing a big space to work in, freed me up financially.

In the beginning of 1976 I visited New York for an extended time with the idea that I would try to put on a show so that people could see what I was doing. The art community was a lot smaller than it is today so it didn’t take long to get a feel for the scene and find out where to go to connect and to participate. I learned it was possible to rent Artists Space for a performance. Helene Winer, the director at the time, was surprisingly receptive to me doing a performance there with only a couple of stipulations: I could not advertise and use Artists Space’s name or claim them as a sponsor and the audience would be strictly by invitation. Basically I had to pay someone to open the space, turn on the lights, sit in the office and lock the door when it was over. I did a performance for a small audience, and in attendance were Martha Wilson and Jacki Apple. I think through them, word got to Marsha Tucker that there was this stand-up comedian performing in the art context and the next thing I know I get a call from her to come to her office to meet, which led to an invitation to perform in the performance series she organized at the Whitney in early 1976, Four Evening: Four Days. Thanks to Martha, Jackie and Marsha I got an immediate New York validation, making my transition and move to the city the following fall very easy.

During this same visit I met Stuart Sherman and not only felt a connection with his work but realized I was not isolated and that were others involved with a kind of theater of objects, mixed media on a small personal scale. The connection with Stuart assured me that I was not working in a vacuum. It was the performance at the Whitney gave that gave me instant credibility not only in New York but also back in Chicago. It was very encouraging and exciting.

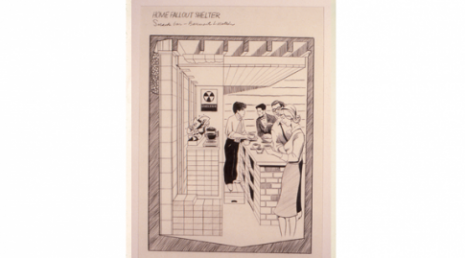

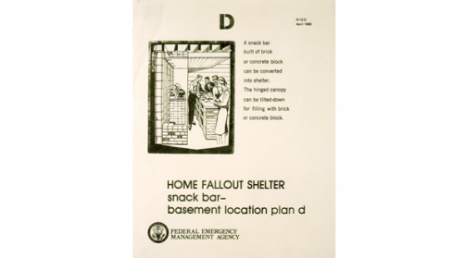

I also had early support from commercial galleries. Marvin Heiferman, the director at Castelli Graphics, was a major booster. He put me in a couple of shows in their 77th Street gallery, invited me to do a performance in the space and, later in 1983, I installed the large scale Government Approved Home Fallout Shelter Snack Bar there. Patti Brundage, the director at Castelli on Greene Street, was also a huge supporter. She showed my videos and added me to the roster of the Castelli Sonnabend Tapes and Films catalog. I made zero money but the certification was incredibly encouraging. The galleries gave me more credibility but did not pay my bills. It was the funding organizations and non-profits that allowed me to work full-time at my artwork.

I was busy and back then had the energy to continually look for new opportunities. I was also lucky to be at the right place at the right time and seem to fill a niche for funders looking to support work that seemed more populous and less hermetic than what came before. I was part of a generation of artists working with, and interested in, media and popular culture, who did not see strict divisions or restrictions of content or context. It was a combination of boredom, ambition and naivety that kept me trying out new venues and directions. As for HBO, I should clarify that Mike’s Talent Show ended up on Cinemax but that all our business was done with HBO. As for my trajectory around the art world, I did not distinguish between one context and the other. I eventually found out there was a big difference between the world of art and commercial entertainment and learned to appreciate the openness and open-endedness of the art context.

I really thought the puppet shows I did with Doug Skinner would be the thing that would allow me to crossover to a more mainstream arena. They were by far the funniest stuff I was involved with. I think our timing was off. This was before Beavis and Butthead and South Park. At the time potty humor was not celebrated in the media. The Henson’s liked our stuff and were big supporters when it came to their puppet festivals. However they did relegate us repeatedly to the fringe festival. I think it was the potty humor.