Literary Agency

Curator Gilbert Vicario* conducted the following interview with Martinez via email during the month of March 2014.

I am fairly certain I don’t know how to answer this question, for the reason that I have no memory of any clear beginning of my life as an artist or the manner of its evolution. My approach to a conceptual practice, it seems, is less something we do and more something we are. Less a piece of life and more all of life. Pieces of things I remember are closer to everyday life intermixed with a lifelong curiosity and devotion to the co-mingling of poetry and philosophy, art and politics.

Events that were seared into my mind, for example, begin with the Watts Riots in 1964, as I lived close to them when they occurred. The student riots in Paris and Mexico City in 1968, and the black power salute at the Summer Olympics in Mexico City of the same year. I happened to be there when the 1972 Olympics when the hostage crisis unfolded. Then there was the Red Army Faction (or Baader-Meinhof Group) and the German Autumn incident in 1977. The Black Panthers, the Vietnam War, Patty Hearst and the Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA). The events in the world that helped influence my ideas seem endless. I also attended CalArts in the mid-1970s and was taught by Michael Asher, John Baldessari, Douglas Huebler, Judy Phaff, John Brumfield, and Robert Cummings. Then I studied with Klaus Rinke who in turn exposed me to Joseph Beuys. Then the philosopher and political theorist Herbert Marcuse came into view. The ideas of post-studio and institutional critique were introduced to me and I was like a crack addict for them. Everything I had been thinking about finally had a form to live in. I couldn’t get enough, the more I was exposed to intellectual and aesthetical ideas, the more it seemed to trigger a cascade of new possibilities, new propositions. Finally I started to understand the urgency of the world I lived in and began to apply the tactics of raw conceptualism.

Somewhere in between these events and my everyday life in Los Angeles, poverty, violence, criminality, gangs, drugs, and the necessity of survival in every form, manifested a new sensibility and a new identity that lived in a constant state of flux. This, and much more, was responsible for the formation of my artistic practice and life.

…And of course Disneyland and Hollywood – can’t forget those.

That’s the beauty of Los Angeles and, to a larger extent, California; they are hovering on the edge of illusion, mind bending realities that, in one instance, are too fantastic to be true and, at the same time, are at the forefront of political, social and cultural eruptions. In many ways there couldn’t have been a better place to grow up; the influences embrace the breadth and depth of our imagination as humans. Thinking about it for a moment, Hollywood and Disneyland are only the beginning. What about military industrial complexes, jet propulsion labs, NASA, Silicon Valley, the largest open border to Mexico and the Americas, serial killers, cults, riots, revolution, mass murder, gang war of new proportions, anti war movement, free speech, rock, punk, hip-hop music, gangster rap, the Pacific Rim, an ocean of sublime beauty, space and light that is so wondrous, just to name a few of the possibilities. Why wouldn’t you want to live your life here? If you look at Los Angeles, San Francisco and San Diego they form a three-way axis for what the future could be. California truly embodies the last gasps of truly radical ideas; it is the portal to galaxies beyond our imagination and the last line of defense for an imagined future. At the same time it masks a hyper-conservative side, a peculiar composition that is somewhat like living in a paradox wrapped in an enigma. California is utterly complex and allusive and in many ways defies categorization or definition. This is both its strength and weakness, regardless of its geopolitical territory, its posture or its tendency to the left or right. It is not intimidated by the detritus of the east coast or Europe. California has been consistently defiant and remains politically, socially, culturally and ideologically autonomous. It is the site of political and aesthetic obsession, an explosion if you will.

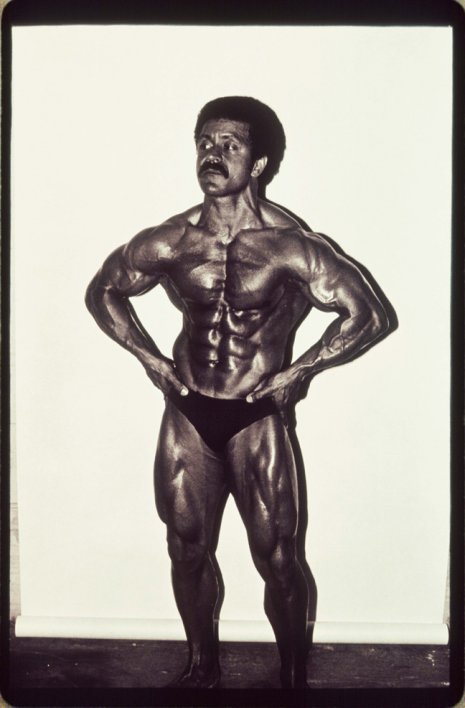

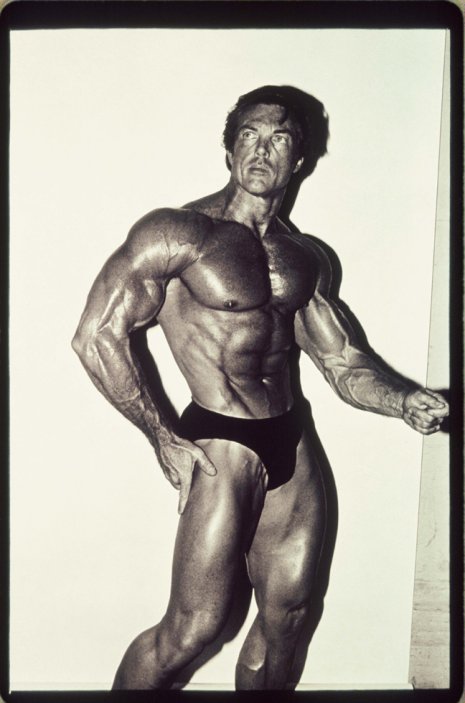

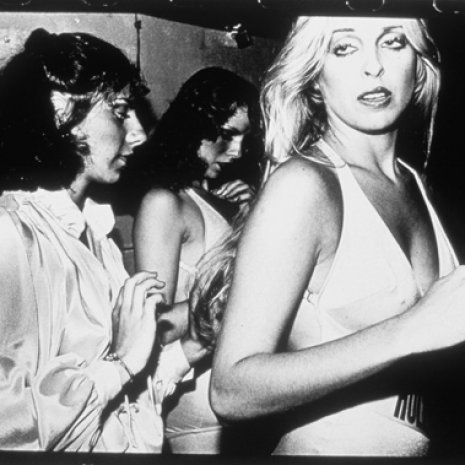

The late 1970s were openly political, and the needs to both embrace and contribute to a movement to diversify the otherwise conservative, narrow, exclusionary and overtly racist environment was at the forefront for “minority” artists in this country. The works you are referring to I believe allowed me to make critiques of institutionalized positions represented through gender, race and gay male politics through the representation of the body as an exposed site where performativity was openly exposed through public forums like beauty pageants and the very early days of body building here in Los Angeles. This was ground zero for both these gendered roles of representations of the extremes of female and male body modification. A space was cracked open to examine these two forms of the body exposed publicly in tandem and in contrast to each other's political assertions. They are as equally grotesque as their aspirations towards ideal beautiful. This was the height of public competition to test the boundaries of what we thought of as acceptable representations of beauty and sexuality. As a forum of public display and performance that was openly embraced, it was equally true there was another formation of identity that was equally hidden underneath these illusions of the body perfected.

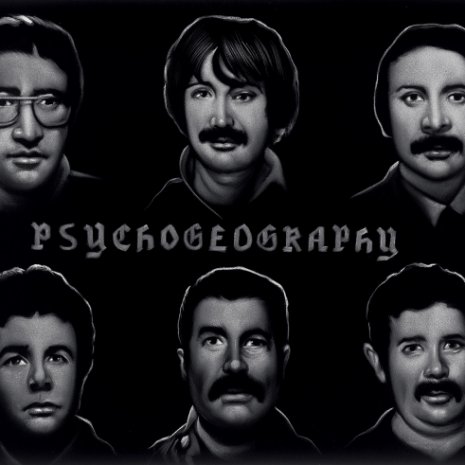

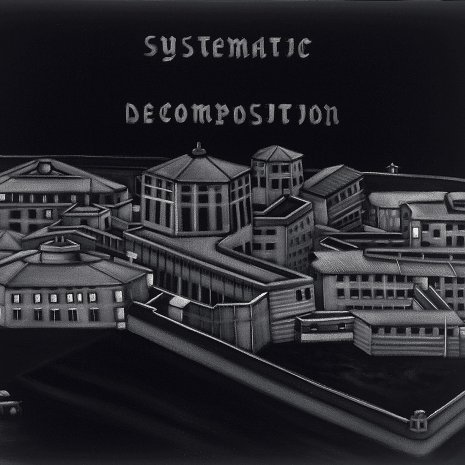

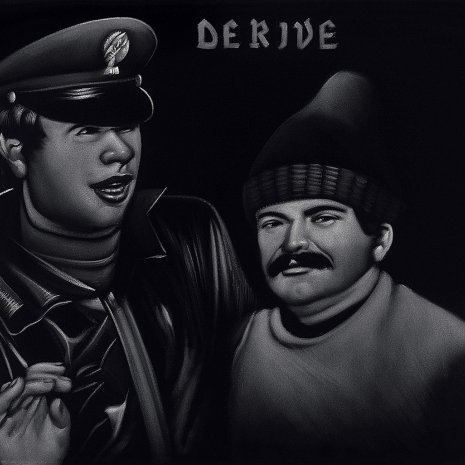

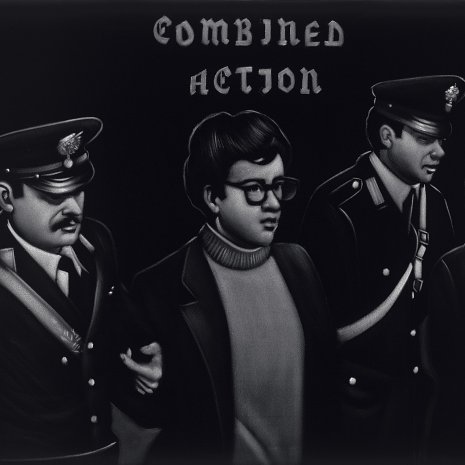

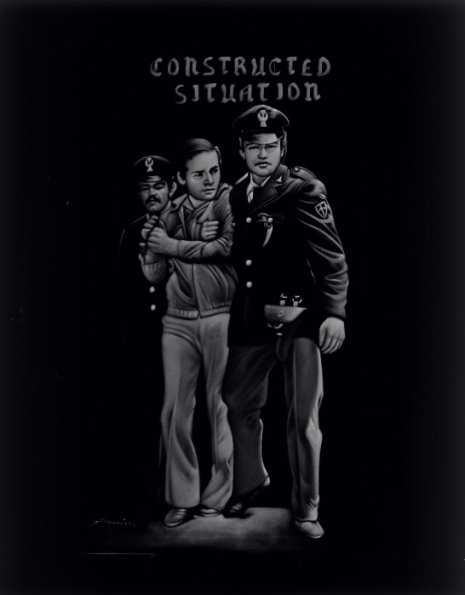

I very clearly remember Angelyne. You never knew exactly what her image meant or why it seemed to be everywhere in Los Angeles; there was no information other than her trademark portrait, the color pink and her name. It was clear it was for self-promotion but “why” was the more interesting question. I had always felt some strange sense of wonder each time a new one appeared. Debord has always had a strong influence since I was young up to my most recent show; his ideas are as vital today as they were in the 1960s. The questions around psychogeography, or derivé**, political events as social structures and systems; the ongoing performative political theater of an endless traveling through time and space to challenge the dominant dogma and conventions of everyday life. One of the persistent questions flows from the fluctuating phenomenon of the unknown possibility of political events in the public domain. Daily events mutate and convert into social space as reflected within the landscape as a field of action, an arena of social-political combat. How can we emerge with a new understanding of our surroundings that suggest new relations and meanings through re-contextualization? Can we focus ourselves towards challenging, unpacking or putting into question discursive and historical mechanisms? Can we examine representational systems that were traditionally used as tools to convey meaning, truths or political ideologies, and convert these into new propositions and paradigms of unknown origin? I am very invested in the obsessive and consistent attempts to wrestle with the underlying madness of everyday life amidst political turmoil that has spread throughout every corner of the world like potent viruses. How do we focus on the strain between society's aspiration for progress and the cyclical nature of history?

Given, however, the gravity of the crisis that confronts us today, I am left with similarly pressing questions: how can other modes of symbolic inscription and other forms of representation be conceived? How is it possible to escape the logic that consists in formulating one’s own disappearance or one’s own incapacity to produce meaning? How can we represent ourselves in a history that is being written in terms of the neo-liberal economy, the free market and the corporate museum? How is it possible to escape the logic that consists in formulating one’s own disappearance or one’s own incapacity to produce meaning? These are just a few of the probing questions that prod my mind and the world we live in. I find myself left wandering the streets of a sleepless world wondering if we will survive and if it’s possible to conceive of a new emergent aesthetic in the 21st century?

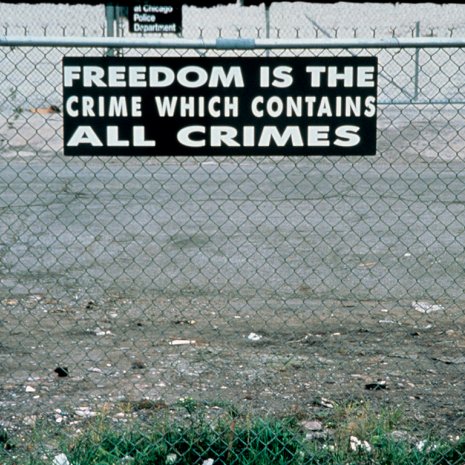

Text has been present in the work since the 1970s. Language in multiple forms demarcates clear sight lines in the work through the decades. As an illustration, the visual and critical tools made available can be articulated with the points of two parallel Cartesian lines intersecting at infinity. One line is the minority position of civil rights, feminism, student unrest, multiculturalism and queerness as a social/political platform. Combining these positions took on new formations of structural and theoretical agency when grafted onto the other critical line of 70s: conceptualism, post studio practice, institutional critique, the rise in photography and language, language as image, language as forms of poetry, advertising, fiction, politics, terrorism and love. These varying strategies and operations were the perfect cocktail to wage a new war with radical beauty, language, social political, geopolitical aesthetic arsenals at the dominant hegemonic, conservative, colonialist, capitalist juggernaut scorching the earth of everything that stood in its path. It was all too clear that in order to survive within the hostile environment of the United States, new strategies and tactics had to be invented. Art and language as a form presented endless possibilities. Procedural operations that had the ability to shape shift and endlessly remain in flux provided a unique opportunity to use past present and future history with autonomy and without explanation or apology.

As Edward Abbey said in 1975, this is jihad pal.

As I look back at the 1980s, they now seem as a preparation for what I could not have known would be the 1993 Biennial. Not only the ongoing experimentation in new work and projects, but I realized I had to take responsibility for my own education so I started reading and books became my own form of heroin. I sought out the historical, theoretical and philosophical knowledge that was mandatory to my being an artist, which to this day has never stopped. Reading became an addiction. It started with Socrates then became a blur… Diogenes, Plato, Saussure, Wittgenstein, Aristotle, Augustine, Adorno, Benjamin, Bloch, Brecht, Lukacs, Gramsci, Arendt, Habermas, Nietzsche, Marx, Marcuse, Kant, Sartre, Descartes, Althusser, Lenin, Foucault, Hegel, Freire, Trotsky, Machiavelli, Hannibal, Genghis Khan, Alexander, Deleuze, Barthes, Sun Tzu, Galileo. Then it just went wild, it was out of control. I started consuming everything I could in every field of study: science, math, geography, history, war, politics, technology, medicine, physics, astronomy, space travel, science fiction, poetry, disease, madness. Everything was fascinating to me, each author and book. Every subject was another step into new worlds which I now craved like I was a vampire of history and knowledge.

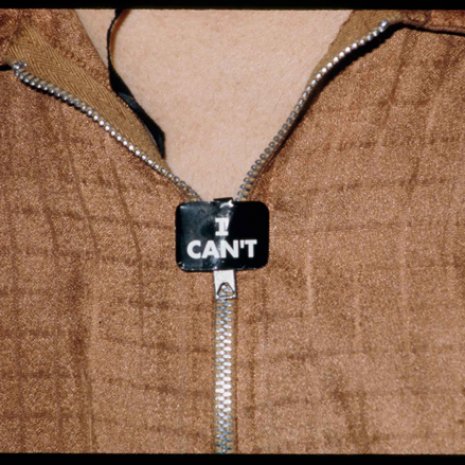

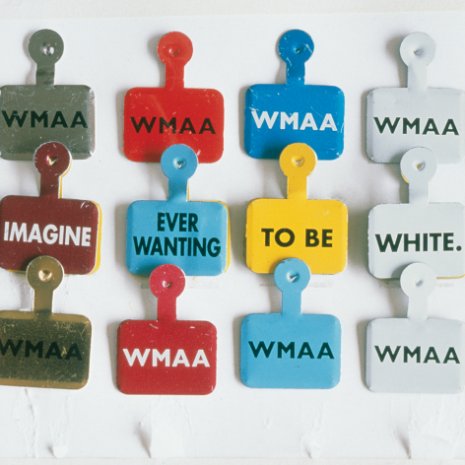

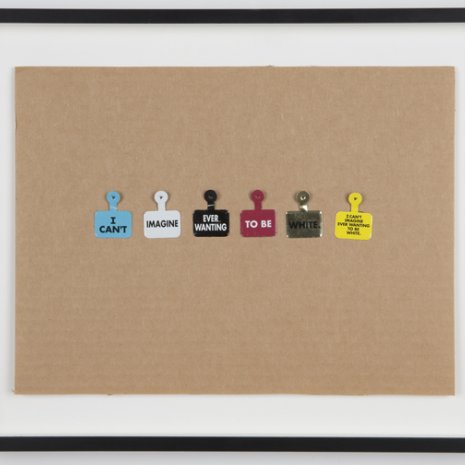

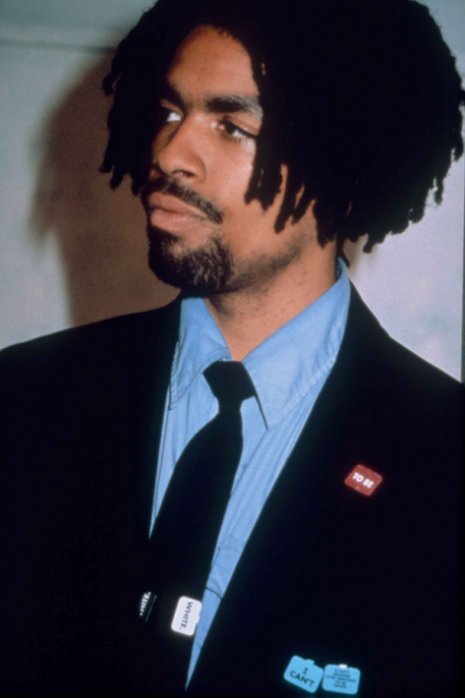

The stars aligned at the 1993 Whitney Biennial with the museum tags. It was a unique opportunity to condense into a single, multi-dimensional gesture one brief moment, one work, a performative use of language through the structure of opera. It was a chance to expose the entire population’s docile, complicit behavior realized by living in the borders of the empire. By our very nature of being U.S. citizens we are directly tied to and support the U.S. corporate, institutional, militaristic, democratic, capitalist, global economy, the operations of social, economic control and discipline. We are witness to the administering of the U.S. global society of control. Michael Hardt and Antonio Negre said, “The Empire is materializing before our very eyes.” Deleuze and Guattari wrote, “We do not lack communication, on the contrary we have too much of it. We lack creation. We lack resistance to the present moment.” And Karl Marx: “This is the abolition of the capitalist mode of production within the capitalist mode of production itself, and hence a self-abolishing contradiction, which presents itself prima facie as a mere point of transition to a new form of production.” The museum tags were, in essence, an aesthetic political manifesto, a linguistic paradox, an act of poetic terrorism, and a declaration of war condensed into one line of poetry.

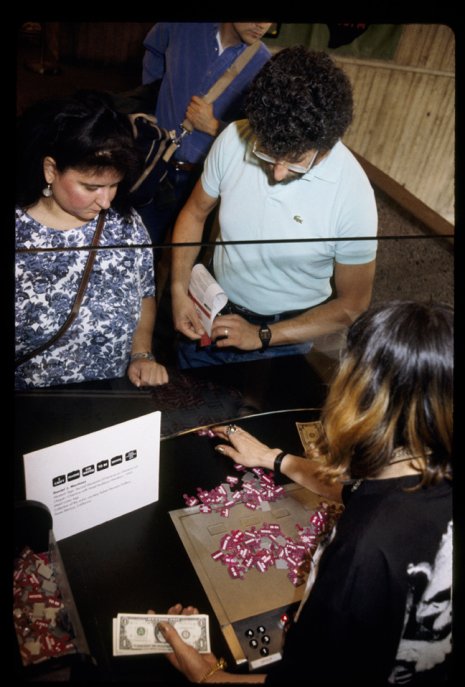

If viewed as a performative intervention into the museum’s existing operating structure, several simultaneous operatic movements appear as chance or random procedures with wide ranges of unknown outcomes. First, as museum visitors go to pay their admission fee, they are normally handed a small metal tag with the letters WMAA (Whitney Museum of American Art) of varying colors depending on the day of the week. It’s a built in security system for the guards to readily see if you paid admission for that day. I replaced the original tag with five different tags containing fragments of the statement: “I can’t image ever wanting to be white.” A sixth tag had the whole sentence. When you paid admission, the staff person at the counter randomly gave you one of the six possible tags. The entire work was in front of the cashier who I had instructed to vary the distribution as much as possible, even handing out the same tag several times in a row. The visitor had to then mandatorily wear the tag while viewing the biennial.

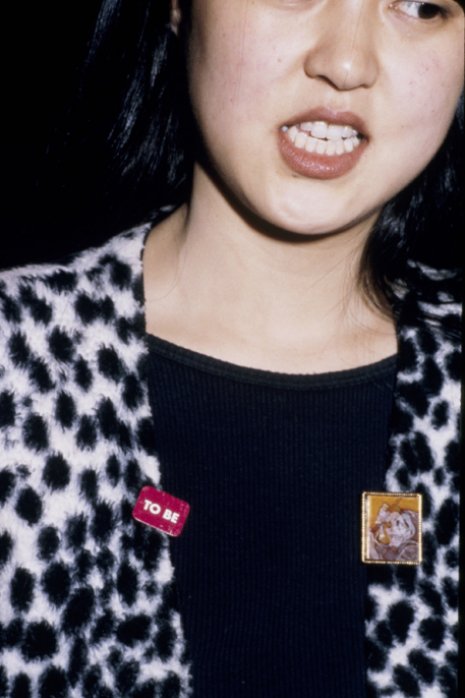

This triggered the second operatic movement where the text was fragmented and changed with each and every person wearing a different piece of floating text fragments. The relationship between the individual viewers wearing a specific text fragment also changed through the meaning/identity of each person. It also changed the entire organization of the original phrase according to the movement and grouping of the visitors as they moved throughout the museum. This set in motion a dance of new meaning everywhere you looked, and a dance of shifting and changing identities of the audience-as-performer-as-language.

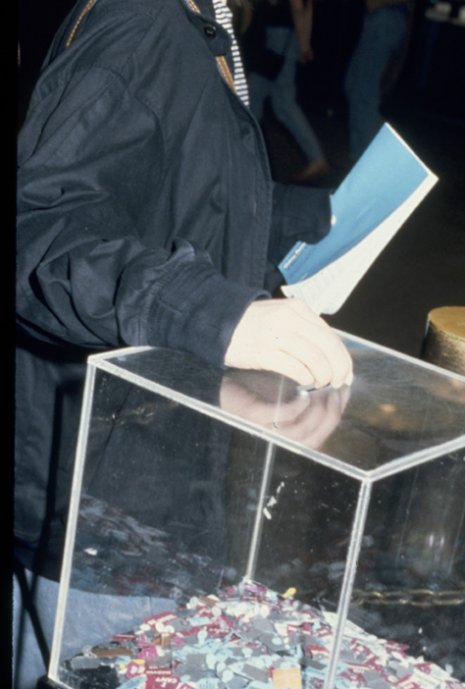

At this point, with endless new combinations of language, the work became a pageant of chance and new and unpredictable associations and interpretations of the original phrase. The next phase or movement, when exiting the museum, visitors could choose to discard the tag in a collection bin, walk out of the museum and throw them on the street, or the subway, or keep the tag until they got home. Once people understood the game of how the work functioned, many audience members came back many times to collect the different tags to reassemble the original phrase. This added yet another dimension, extending the original performance through the repeated cycles of coming and going back again and again.

One last random event involved the museum guards who normally cannot wear any jewelry or adornments on their uniforms. I asked if they could wear the tags, and, being that this would become part of the artwork, the museum curators and director agreed. This enabled the guards to express themselves with the tags by not just wearing one tag but, if they chose, many tags at the same time. This gave them the ability to organize the language, to make new formations of words and meanings that differed from the original text. It was a fascinating moment when a free hand was given to the guards who indeed saw the power of language and asserted it each day in new and different configurations. In the end, it was quite an extraordinary chain of events, started by the desire to enter the museum and view the exhibition.

The work you are referring to was a series of performance photographs inspired by Nietzsche’s essay “Twilight of the Idols, or, How to Philosophize with a Hammer.” My work was titled Coyote: I Like Mexico and Mexico Likes Me (more human than human), 2002. There were approximately 14 different performative self-portraits done only for the camera where I systematically altered, mutilated and/or deformed my body in the attempt to destroy the ego of the self through the physical dismemberment of my body. Given that they were very labor intensive to create, perform and photograph, these were created over a number of years. Each work was an interpretation of an historic painting, film, mythological event or person, or actual historic event. Using sculpture and prosthetic augmentation to create these physical deformities was a long, durational performance, some lasting 12 to 14 hours to create a single photograph. This was after 6 months to a year of preparation in the sculpting, mold-making, body casting, and fitting as close to perfection as possible to achieve the desired effect.

This was an all-analogue process; no digital effects or Photoshop were used in the creation of these works. The structure of each was not only closely related to Nietzsche’s ideas of the killing of all our gods, idols and ego, but also to the imagining a new future for the human species. This held a further potential towards the possibility of becoming more human and even super human in the process. The labor-intensive process of remaking my own body in these images as a form of ideological metamorphosis felt physically akin to Mary Shelly’s creation of the monster out of dead body parts and a deformed brain, and Kafka’s proposition of psychosocial transformation from human to insect.

These performative events set in motion an interrogation of my unconscious desire to investigate the possibility of the aesthetics’ of murder, torture and genocide as possible political sites where the body mutates into a trans-psychological species where one could, at the same time, reach the point of being both moral and ruthless without conscience. To remain with love in our hearts and yet have the strength to cast out and destroy the old notions and conventions of what we have traditionally believed it means to be human. We must risk the transformation of becoming, being more human than human. To do this we must first destroy ourselves, destroy the first idol or god: the self. It is preferable to be dead than to be what we are, zombies walking around without purpose or vision, in a world where the stench of our rotting flesh is all we know.

""Reading became an addiction. Every subject was another step into new worlds which I now craved like I was a vampire of history and knowledge.""

The Politics of Falling, by Juli Carson.

A Modest Propsition, Art Journal, 2005.

""There are many great advantages to be had workig inside the empire, but simultaneously it's like having one's hands tied. Subjects and topics that are at the point of crisis, catastrophe, disaster, and social extremity are mostly denied, avoided or outrightly dismissed in the United States.""

*Gilbert Vicario is senior curator and division head for curatorial affairs at the Des Moines Art Center. Recent exhibitions include Phyllida Barlow: Scree (2013); Single-channel 4: Gravitas (2013) featuring Gilad Ratman (Israel), Adel Abidin (Iraq/Finland), and Richard T. Walker (San Francisco); and Leslie Hewitt: Untitled (Structures) (2012) in collaboration with the Menil Collection, Houston and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago. In 2006, Vicario was named Commissioner for the International Biennale of Cairo by the U.S. Department of State for the exhibition Daniel Joseph Martinez: The Fully Enlightened Earth Radiates Disaster Triumphant. Vicario is a graduate of the Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College (M.A., 1996) and the University of California, San Diego (B.A., 1989).