Chapter Two

AC:

Is there also a spiritual primitivism that coheres to blackness? In popular culture, it is often black characters who can see beyond physical space. How does that connotation of our perceptive ability to see also refer to medicine men, or witch doctors?

SL:

I am interested in mechanisms and strategies of self-defense. It was my friend Aimee Cox who said that we have evidence that black people had to develop strategies of know-how to take care of ourselves. That fact that we did so is proven because we still exist. Growing up in a monolithically African-American culture in Chicago, everyone was black—the doctors and the nurses. We had groups such as Jack and Jill, The Links and, to a certain extent, the Deltas and AKA, which organized cultural work and training in terms of thinking about protection, and networking. I’m not aware of such a plethora of private groups in Jamaica and other places where black people are in the majority.

AC:

Did this childhood in an all-black culture lead to an awareness of the Order of the Tents?

SL:

No, I didn’t grow up knowing about the Order of the Tents. A friend told me that she had read in Brooklyn Brownstoner about a mansion that developers were trying to buy. The article reported that now it was owned by a secret society of black nurses called the United Order of Tents. After reading Alondra Nelson’s book on the Free People’s Medical Clinic (FPMC) about the less publicized aspects of the Black Panther Party, I wanted to focus on self-care as an often overlooked but insightful strategy for artistic and social advancement. This society of black nurses dovetailed with my budding understanding of black radical medicine as a social necessity. These nurses operate completely in secrecy and were only known publicly in the south, where they host some “public” days. As the oldest Christian fraternal organization in the United States, they’ve been doing good works since the Underground Railroad and even through the Civil War.

AC:

It is amazing that I was not aware of them.

SL:

Others of my very educated colleagues had never heard of them. When Creative Time asked me to do a performance, I envisioned a project that would involve self-empowerment and self-defense strategies in this community of Brooklyn. Black nurses would allow me to continue to draw attention to labor and labor as a performance. Just the idea of the existence of the United Order of Tents was so thrilling.

AC:

How do you contact a secret society? Was there a meeting in the dark behind a linden tree?

SL:

(Laughs) I called the publicly listed Virginia telephone number and woman answered the phone. She said, “United Order of the Tents,” like that. (Laughter) I couldn’t get it together. I had to hang up and call back. I thought, no way is this actually happening. So many secrets are in plain sight.

AC:

Even after slavery, reconstruction, and the civil rights movement, why do you think that there is this need for privacy within the African-American community?

SL:

On many occasions, visibility for African Americans has been life threatening. For example, Mother Emanuel’s church had to go underground for 35 years after Nat Turner’s rebellion. You’re not really allowed a complete humanity in public. Important narratives in African-American culture have been organized in private in groups and societies that by intention must be either private or secret.

Privacy seems especially important for these secret health societies because, for example, police frequently greeted Black Panther doctors, who came to help community members, I was told by two doctors who visited my project. They said the facade was barricaded outside with sandbags emulating a mini-war zone. This image of the outside of a health center replicates the fractious relationship with the Black Panther and the police that we know from history. The inside then becoming, we assume, a kind of bunker. My project done in collaboration with Stuyvesant Mansion, which is the former home of Josephine English one of the first black women gynecologists in NY who delivered all of Malcom Xs children. Her one exist as a community center now. My project there was eventually called Free People’s Medical Clinic (FPMC), 2014. I took the title from these unknown Black Panther community-focused healthcare initiatives in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. I wanted to explore privacy as a site of resistance and disobedience in order to achieve survival.

AC:

These were organizations actively advocating for black health and therefore they had to assemble in private in order to avoid spectacle and derision. Is there also something else at work here about alternative healing practices. I am from Jamaica and it is a very superstitious place with all sorts of ways to heal common ailments. I know that your family is from there too and I want to know if your interest in alternative medicine stems from this.

SL:

People often ask me if I am Jamaican. I was born in Chicago, but of course culturally I am very tied to the island. I am always investigating crossovers between initiation rituals that have been passed down from West African cultures and their diasporic resonance. Food, culture, ritual and medicine are all intertwined. Have you read Zora Neale Hurston’s description of ritual in that passage, called "Curry Goat?” I’m a little obsessed with these kinds of things, this idea of secret rites.

AC:

Is that from "Tell My Horse: Voodoo and Life in Haiti and Jamaica"? I don’t remember the curry goat section.

SL:

Zora is hanging out with Harlem intelligentsia including Claude Bell. He begins to tell her that black American women are not trained in bed the way Jamaican wives are. Bell stated, “Western women had not given up on the idea of mating and marriage altogether, but many men and consequently women in Jamaica are better informed. Before long, he drove away, and he had told me about the specialists who prepared young girls for love.”

AC:

(Laughs) You don’t feel comfortable reading the rest of the passage.

SL:

No. Just not all people enjoy being read to; most prefer to read to themselves.

AC:

{Zora goes to Jamaica and convinces the older women to allow her to observe the preparation of a young bride.} “For a few days, the old woman does not touch her. She is taking her pupil through the lecture stages of instruction. Among other things, she is told that consummation of love cannot properly take place in bed. Soft beds are not for love. They are the comforts for old and lackadaisical. Also she is told that her very position must be an invitation. When her lord and master enter the chamber, she must be on the floor with only her shoulders and the soles of her feet touching the floor. It is so that he must find her. Not lying sluggishly in bed like an old cow, and hiding under the covers like a thief.” Wow!

SL:

I used a page of this text as the invitation for one of my first solo shows at Rush Arts Gallery. Many people were a little freaked; so, yes, I have been thinking about healing and initiation rites for some time.

AC:

Private healers and advice givers seem to buttress other major themes in your work of knowledge transference. Is this concern purely derived from your training in philosophy and your post-colonial interest in Edward Said, among others, or are there other more personal engagements?

SL:

Yes, vernacular knowledge, which is accessed outside of mainstream, is a primary focus in these re-enactments. At various points in my life, I’ve had to find many different kinds of knowledge on my own.

AC:

In our modern world, our sex education is packaged and handled on a state-to-state basis. and our education about gender, culture, race, at times is ancillary to the mainstream and is not carried out in a culturally agreed upon manner.

SL:

Yes, older forms of medicine and advice were considered obsolete because we improved medicine and advice. So the question becomes where does our advice come from and in whose interest does it serve?

AC:

So, you are working on a second iteration of the "FPMC" called the "Waiting Room"?

SL:

Yes, at the New Museum. I have more freedom because everyone walking through the door knows that it’s an artwork. I don’t have to explain what my objectives are like when we installed it in Bed-Stuy. On the other hand, the museum is not free so it’s not an appropriate venue for a re-enactment of, say, the Black Panther Party’s clinics, which the first iteration largely was. The project has shifted also because Black Lives Matter formed and flourished during the time of the first clinic. The notion of self-preservation took on special meaning. My adjusted focus is on two things: One is the status of waiting, as a psychological preoccupation, and how it relates to black women; second is the creation of safe spaces so there can be a site to strategize beyond the meagerness of survival. Hortense Spillers has a passage where she describes black women as being vestibular to culture in general, and I’m interested in this sense of waiting as a presumption that black women must have a kind of stamina, and how we can move beyond the ancillary towards efflorescence.

AC:

Were there any art precursors for your project? Other artists that you are in dialogue with?

SL:

I'm interested in diaspora and knowledge transferred from women to women, which often manifests as intergenerational knowledge sharing. I’ve collaborated often with Chitra Ganesh, we form a collaborative called “Girl” and she has created a project with Mariam Ghani called Index of the Disappeared which documents redacted knowledge among other things.

There are other artists dealing with vernacular knowledge and self-preservation strategies

such as Suzanne Lacy’s University of Local Knowledge, 2000-2006. Her project was in Bristol, UK in a working class community of factory workers that was decimated by unemployment; she went into the community with volunteers, who documented local forms of knowledge, such as how to feed a family of four on $400 a month or how to take care of a horse…They did sound and written recordings and put them into the Knowle West Media Center. Kameelah Rasheed’s project “No Instructions for Assembly” is a personal archival project which I admire. Finally, there is Lorraine O’Grady’s website with its 250 pdfs of her writing, my favorite archive right now. I think I’m not the only one who visits the site as a regular past time.

AC:

Your discussion of a localized knowledge of health reminds me so much of Fred Moten and Stefano Harney’s discussion of the Black Panthers commitment to self-defense and revolutionary activity. They discuss the extralegal status of the Panthers.

SL:

The practitioners at the FPMC continued that tradition. Now community members also operate in the arena called "alternative health practices." I met Karen Rose in Brooklyn, an internationally known master herbalist. She has brought focus on how the process of how medicine is acquired is also the medicine. Song for example. She has said “The song is the medicine as well as the herb that the song was sung about.” Its how you got to know how. In this case how to heal oneself with plants.

AC:

Would you talk about formal issues of privacy in the "Waiting Room"? As you started to tell me, certain installations or performances would be visible in either the lobby of the museum or could be visible in other spaces through video projection.

SL:

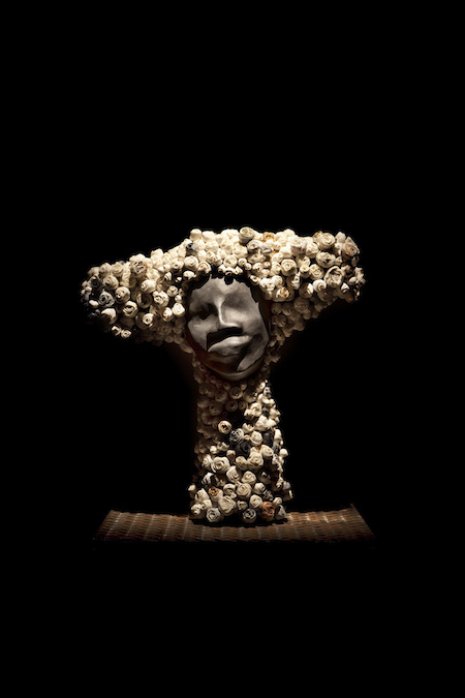

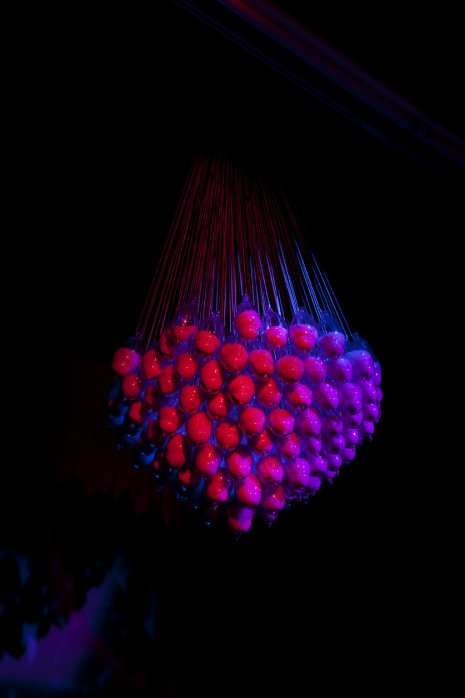

As you know, I am in the midst of planning a residency which will take form at the New Museum this summer. There will be contributions from scholars like you; there will be healers; and there will be an “underground” series of workshops called Home Economics which will cater to the needs of black girls when the museum in closed. In the original incarnation of the FPMC, we published a Waiting Room magazine. Naomi Jackson wrote about Edith Edim Green, a Jamaican immigrant who tried to check herself into the Kings County hospital in 2006 and died after 24 hours of waiting for care. I am interested in how some mechanisms of care are visibly functional or dysfunctional. In the current Waiting Room, Aimee Cox will teach a class that we call Afrocentering. Cox has written about the ethnography of homeless girls in Detroit. She describes citizenship as something these girls have to choreograph. They have to self-preserve. Melancholy, self-sacrifice, stamina, these are the conditions that we associate with race. In Anne Cheng’s scholarship, and others, the dynamics of these conditions are constitutive of race. I want to offer a focus on stamina as foundational for racial identity. In my work, I refer to the navigation of these ways of constructing a self through the secret, overt, the private and public. Akin to my formal strategies with the ceramics, I quote quotidian forms while transforming them again and again in order to explore the residues of power that adhere to objects and actions.

“When you are making objects that intersect with black culture and bodies, the approximation of the real becomes a question asked often of you.”

“At various points in my life, I’ve had to find many different kinds of knowledge on my own.”