Chapter One

Thomas F. DeFrantz* and Ishmael Houston-Jones met in 2005 on the campus of Duke University in Durham, NC when Tommy was teaching theory and history in the Hollins University/ American Dance Festival MFA program and Ishmael was teaching improvisation and composition at the festival. Over six weeks this spring, they exchanged emails.

Thomas F. DeFrantz:

Dearest Ishmael,

I am thrilled to work with you again in this way, and even happier to learn the joyous news about your receiving the Herb Alpert Award! So very well chosen, very very well chosen.

SO, we create a dialogue for the website and a way for others to come into the world we share, and that you make, together.

Thanks for this opportunity.

A first question then:

In your creative craft which includes dancemaking teaching performing and curating, you are emphatically and ecstatically concerned with the presence of people who are not here – young artists who have not been given a chance; friends and lovers who have died too soon; families who don’t go to experimental dance events on a regular basis; bodies of color in white spaces. You seem to constantly remind us that there are others; that there have always been others, and will always be. How do ghosts or hauntings factor into your work as an artist?

Thanks friend, and away we go …

In motion, td

Ishmael Houston-Jones:

Hey, hey Tommy:

Here goes.

Note: I always capitalize "Black" when referring to a people.

x,

- I

The fractured narratives in the spoken text in my pieces usually can be characterized as autobiographical fiction. That is, the events I’ve lived through, the things I’ve witnessed, relationships I've had, emotions I’ve felt – all of these are fair game to be used in my work. But I am neither an historian nor a penitent but an artist, so I use this information as source material, that I then shape and manipulate into performances. Now many of the facts of my particular life position me as an outsider. Being an only child, being Black and lower middle-class in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, taking family road trips to Mississippi in the 1950s-60s, at age 11 being removed from my mostly Black elementary school and placed in a class for “gifted” children where mine was the only brown face in the entire building, being a self-defined radical/hippie, having a gradual evolution toward a bisexual identity, dropping out of college to work raising pigs in Israel, going to Nicaragua during a civil war to teach dance to Sandinista soldiers, being an artist, being a dancer, being a Black queer man during the years of AIDS hysteria – the list goes on and on; all of this makes my world-view that of a person outside of mainstream USA society and it seeps or floods into my work through language and movement.

TDF:

2. Your answer is a great start…but I don’t think it speaks to the question of ‘ghosts’ or ‘hauntings’ – did that question not interest you? It’s okay if it doesn’t (obviously).

IHJ:

I think I passed over the “ghosts” and “hauntings” portion of your question because I don’t look at my work through those lenses. Of course the past is always present in my work, but it is the current situation that fuels the pieces. OK, this is not always true, but most often it is. Some not so obvious examples are DEAD (1981, revived in 2010), Part 2: Relatives (1982), and THEM (1985/86, revived in 2010).

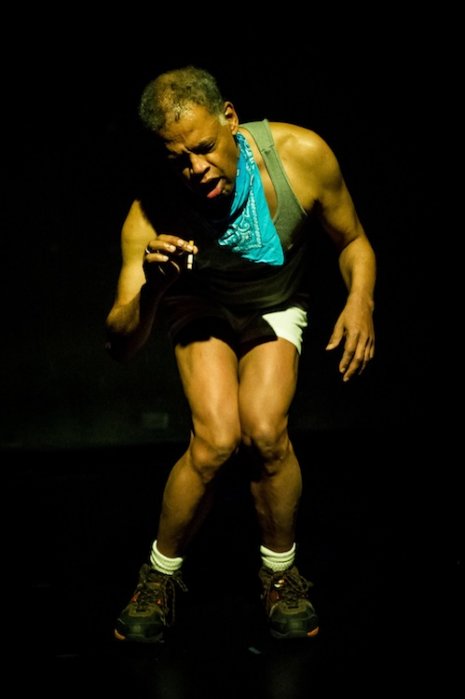

DEAD, on first view, might seem to be inspired by ghosts. After all, when I made it to celebrate my 30th birthday in 1981. I recorded an improvised list of every death - real, fictional or imagined - that I could remember occurring during my lifetime. Included were groupings such as: "Allen’s mother / Jeff’s grandmother / Kathy’s sister / Larry’s Dog,” or “Lassie / Superman,” or “Malcolm X / Helen Keller / Louis Armstrong / Golda Meir.” While all of these names (and the list went on for 10 minutes) were in the most literal sense “ghosts,” my response to each name - to fall down onto the floor in some iconic way and rise before the next name is said - is about my present tense reaction to the memory of the person (or pet or fictional character.) As my recorded voice recited the names in a moderately regular cadence, the exertion it took to fall and rise for 10 minutes made my physical exhaustion very real and in the moment. While this could be viewed as an exorcism or a conjuring, for me it was more of a ritual of endurance. (When I revived DEAD for Philadelphia Dance Projects in 2010, I gave the dancer, William Henry Robinson, the score and instructed him to develop his own list of names of his dead. I helped him edit the list and guided him in the possible responses he could have to each name as he fell and rose.)

Part 2: Relatives, usually abbreviated to just Relatives, did begin with me scattering mothballs in the dark while singing “Here Mothy-Mothy.” And I did an evocation of my known ancestors from my maternal great-grandparents on down while performing a simple spinning dance. These actions definitely signaled an opening up to the spirits. But once I picked up my mother, Pauline H. Jones, from her seat in the audience and lifted her onto my shoulder and started a conversation, for me the piece remained in the here/now. Even when my mother was onstage timing the last 10 minutes of the piece as she improvised stories of our family, my task was to ignore her as I danced and to try not to become ensnared with her memories.

THEM was created in 1985-86 at the height of AIDS hysteria here in New York and around the world. Everything about the dance was immediate and raw. The original music was improvised during performances by composer Chris Cochrane. Only Dennis Cooper’s text looked backward to a past. He recalled a time of youthful desire and passion as well as explosive emotions and violent deaths. My dance with the disemboweled carcass of a dead goat, (purchased from a Halal butcher), embracing it, wrestling with it, sticking my head into the hollowed cavity of its torso was indeed an exorcism of sorts. But it was an exorcism of my very palpable fear of death and disease as friends and lovers were dying all around me. In 1986, the final section, the AIDS coda we called it, with the dancers feeling their lymph nodes at neck, arm pit and crotch was a depiction of the then current practice of (young) gay men obsessively checking for the onset of what could be fatal disease. You saw the revival of THEM in 2010, 25 years after its premiere. While the text, music and dance scores remained virtually the same, the piece could not be viewed with the same eyes. The improvised solo I added for myself at the beginning as an overture, was definitely haunted by the ghosts of the past quarter century. I was remembering lost friends, colleagues and lovers. I was trying to recapture my feelings from 1986. Especially when the revival was performed at Performance Space 122, the venue of the premiere, and where much of my early work had been done, I could feel ghosts in that room as I did that dance. The piece continued with a cast of young dancers, some of who had not been born when the work premiered.

So, I have partially contradicted myself. Yes, there are instances when hauntings are very important to me in the performance of my work even as I endeavor to keep myself responding in the present.

TDF:

3 Let’s try another one.

Your work is often characterized as offering ‘outsider’ perspectives, as you’ve been doing things that others in a mainstream of contemporary dance don’t do. Working in Nicaragua; spending time in Israel on a commune; making works about HIV in improvisational structures that involved spitting. But you also work as a crucial curator and educator for young artists. What does curating or teaching do for you as an artist? Are there things that you hope that young artists learn when you bring them into your orbit, or things you learn from spending time with younger, emerging artists?

Hugger-oodles, td

IHJ:

There was a time, not too, too long ago when I, like many of my contemporaries, saw teaching dance as a necessary occupation I had to undertake in order to supplement what I considered to be my more creative work – choreographing and performing. I’ve recently come to the conclusion that teaching as well as curating are important, even necessary, parts of my creative process and practice. When considering my artistic output, I now consider these endeavors to be equal in importance to choreographing.

It has become a bit cliché but I do learn so much from the act of teaching. As an improviser, it is important for me to be present at every moment of the class. I almost never create a structured lesson plan. When I have done so, the result is usually not very good. I need to be spontaneous in my teaching; each class is a mini improvisational performance, even if I dance very little or not at all. I am a subversive teacher. I plant ideas, propositions, possibilities and impossibilities into the students’ awareness. I rarely offer my opinions of work, even when I’m a mentor. I ask a lot of questions. I think I learn a lot about my own choices by interrogating the raw impulses of less seasoned dance makers.

I’m not exactly sure what my students get from me. It’s probably personal for each of them. Some have discovered that making dances is too challenging and they decide to do something else. I think they learn to think critically about work, their own and the work of others. I think I give them a sense that anything is fair game for material. There must be other things. Many reject the definition of dance they got from their earlier training, as they will one day, hopefully, reject mine.

As for curating, I’m fairly new to the art form. Although I curated the first Parallels series in 1982 – two weekends that brought together the work of African-American choreographers working beyond the Alvin Ailey tradition of “Black Dance.” – it wasn’t until its 30th anniversary when I curated Platform 2012: Parallels that I began to understand the craft of curation. I think finding the right question, and then finding connectivity between different answers is helping me locate my own work. It has taught me how my work connects with work from the past as well as with my contemporaries. I’ve learned how to better reject ideas that don’t fit and to search for newer ways of seeing the world and my work in it.

TDF:

4

This concept of rejection seems urgent here. Rejecting restrictions, rejecting boundaries of definitions, rejecting propriety, whatever that might be. When you write that students might reject their encounters with you, or the terms that you engage with them, I wonder what arrives in place of that which is rejected? Maybe improvisation rejects ‘knowing what will happen next;’ but what arrives in that place of not knowing for you as an embodied artist, what does rejection do for you?

IHJ:

Hmm? I agree with your idea that “improvisation rejects knowing what will happen next.” That “not knowing” is crucial to my practice of performing and teaching improvisation. However, I don’t see this so much in terms of rejection, rather I consider it more of a positive acceptance of infinite possibilities rather than limiting oneself to what is already proven. Although there are always factors which are pre-established in the creation of an improvised performance – approximate duration, location, cast – I find that the less I plan in advance the richer the experience is for me and hopefully for the audience as well. In terms of teaching improvisation, a main goal of mine is to encourage students to trust their instincts and to not to rely upon the familiar.

What would rejection of rejection look like? I hope it would not signal a return to conservatism, but that is a possibility. Cultural pendulums do swing back and forth. I like being challenged by students, (and others). I like to reconsider my ideas and beliefs or at least analyze their origins. I feel that I have succeeded as a teacher when students do not accept what I ask them to do without questioning. When I was teaching choreography critique at the graduate level, I never gave my own opinion in class. I might ask leading questions but I encouraged fellow students engage in the critiquing process. I find in those situations it is almost impossible that the voice of the professor not to be louder than all the others and thus color the critical thinking of students. I believe my mission as an educator is to promote freethinking and not mimicry. In improvisation classes I rarely demonstrate and one of favorite comments after giving an improv prompt is, ‘Was I vague enough?’

TDF:

5.

Ishmael, you are one of the clearest complex thinkers I know, and this is why so many of us turn to you again and again for counsel and creative support. When you ask if you are ‘vague enough,’ I think, ‘hell yes!’ -- enough to allow us all to grow through experimentation and risk-taking. So what risks attract you today? What do you want to try to figure out next that you surely didn’t know yesterday or ten years ago?

IHJ:

Thank you, Sir. I am a Gemini after all and am a bit obsessed with always seeing things in at least two ways. I also have contrarian tendencies; my first impulse is often to disagree.

So what are my future risks? The two things that immediately came to mind were writing and curating. I’m still interested in what it means to place human bodies moving through space and time in front of witnesses, aka creating dance performances. But I want to actually pursue writing. When in high school, half a century ago, I thought I was going to be a poet, a novelist or a journalist. My contemporary inspirational heroes are writers Eileen Myles, Pamela Sneed, my buddy Dennis Cooper, and the journalists Richard Engel and Hilton Als who combine poetics with commentary. It’s not that I don’t appreciate good dance making, it’s just that right now I find very little of it inspirational.

But back to your question. I am a good writer; I am a terrible editor. I think it stems from my practice of Improvisation. I love that initial moment of leaping into the unknown and trusting what will happen will happen whether I or anyone deems it ‘good’ or ‘not-so-good.’ There are no do-overs in improvisational dance. I love that same leap in writing, except once the initial words are put on the page there is usually a lot more work to do - editing and rewriting and editing some more. At this point I become bored and lazy and lose interest. I recently had a computer melt down and had to have files recovered. In the process of putting old files into my new machine I came across a 33-page short story that I had not looked at since 2010. I reread it, and it could be really good, but when confronted with the work of actually finishing it, I left it untouched on my hard drive. Also, for years I’ve been threatening to write a book on the teaching of Dance Improvisation because I have not been able to find one. I have files of notes and beginnings but no book. So risking letting my writing voice loose and more public is something I feel needs to happen. For some reason this is more daunting than putting dances onstage.

As for curating, as I said, I am relatively new to this practice but am enjoying exploring and developing the craft of the art form. And I do see curation as an art form. When I curate a Platform, (I am in the midst of my second one at Danspace Project in New York,) it is very similar to how I choreograph my improvisations. It’s intuitive creation, shaping a series of activities that answer unanswerable questions. The one I’m working on now, with Will Rawls, Platform 2016: Lost and Found, poses the inquiry: what effect have the deaths from AIDS in the 1980s and 90s and the resultant loss of a generation of mentors, role models and muses had on current dance/performance creation. Particularly work created by queer artists and/or artists of color. It’s an impossible question to answer. I’m curating a negative, a fantasy of what might have happened. I’ve set myself up for possible very public failure, and yes, that feels risky.

TDF:

6.

So we turn around the bend and back toward our first query to bring up the rear … lost and found sounds to be concerned with people and things that were and are not anymore, but are somehow still here anyway; concerned with how change changes things. Can you talk about your own creative work in terms of how things arrive and dissemble; how you have restaged your own works, even as you make new work, how does change change for you?

IHJ:

The two bromides about change that immediately came to mind were that “change is the only constant,” and, of course, “the more things change, the more they remain the same,” which sounds much better in French. But as hackneyed and contradictory as these two old saws may be, I do believe that my belief in “change” is contained in both of them.

A circuitous detour that hopefully will bring me back to your question: Between the time when we began this email dialogue and now, my best friend, collaborator and foil Fred Holland died of colon cancer. And although life had to continue, in the face of choreographing the memorial celebration, writing the eulogy and dealing with the families (blood and chosen) of someone I knew, loved and made art with for over 40 years, things like conversations about aesthetics, deadlines and awards became very, very unimportant. This is neither an apology nor an excuse for a certain lack of focus, but just a reminder that real life events can change a predetermined trajectory. How this relates to your last question: in planning the service for Fred, I enlisted the help of Cathy Weis, a video artist who documented much of a certain subset of Downtown dance and performance work in the 1980s and 90s. I knew she had footage of Fred and we spent several days looking through her archive. Among the pieces we found was a 1983 untitled duet Fred and I made for Contact at 2nd and 10th, a mini-festival at Danspace Project that commemorated the tenth anniversary of Steve Paxton codifying what would become the form known as Contact Improvisation. Since the 1980s I had only seen a four-minute clip of the 30-minute footage, (the duet was about 15 minutes long and was performed on two consecutive days.) I have shown the four-minute version in many of my improvisation and composition classes. I always share the tongue-in-cheek score that Fred and I used as prompts for the dance. Because the raison d’être of the festival was Contact Improvisation, Fred and I created a manifesto (known only to ourselves at the time), that we would do a C.I. duet but we would break every rule of C.I. orthodoxy.

“I love that initial moment of leaping into the unknown and trusting what will happen will happen whether I or anyone deems it “good” or “not-so-good.”