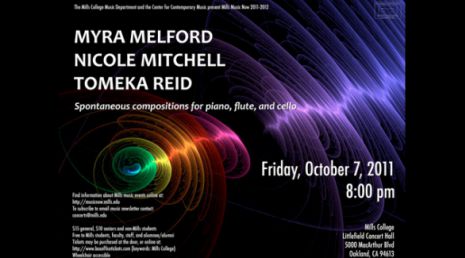

About Myra Melford

Joyous multiplicity and mutable architecture might be ways of describing pianist, composer, improviser, and bandleader Myra Melford’s work. Drawing on many genres, including jazz, blues, experimental practices, Indian, West African, Cuban and new music, Melford’s sounds range from simple, spacious, lyrical melodies and harmonies to spiky, abstract, polytonal and textured passages.

She often begins her inquiries with a physical impulse, or gestural sound, rigorously developing that impulse into a composition or new improvisational strategy with the goal of transcending technique and intellect. "What idea or feeling wants to be expressed now, and how can I realize or facilitate that through music?" she asks.

Melford challenges herself to discover new sounds and forms of expression by playing and writing for many different ensembles, incorporating new technologies and collaborating with artists in other media. Her interest in improvisation and ‘expansive music,’ is rooted, in part, by Frank Lloyd Wright’s concept of “organic architecture;” design not imposed but created in response to function, site, and materials in concert with the site. Melford cites the impact of Henry Threadgill’s notion of “organic composition’ which she describes as “starting with a small cell or musical phrase and allowing a whole composition to grow naturally, through an infinite number of permutations, out of that initial material including the form or structure of the piece.”

Nate Chinen, music journalist and New York Times contributor, interviewed Myra Melford via email, March 2012

I draw great inspiration from other people's creative work and am intrigued by the ensuing cross-disciplinary dialogue. I think of it as a very personal conversation, which begins with a spark of recognition when I experience a given work of art, be it in any medium. Something in that building, the imagery or rhythm in that poem, that dancer's gestures or that painting, speaks to me or moves me, and I want to respond through music. The conversation is both internal--between the active/doer and the receptive/perceiver within me, and external--between the artwork that inspires and the musical response. It's a very rich and engaging process on many levels: emotional, intellectual, physical, spiritual, and one I return to again and again in my work.

In the end, when I'm successful, i.e. happy with my work, I think these two modes of response become synthesized to a point where I can no longer identify what's cerebral and what is intuitive or visceral. Certainly, if I analyze my process, I would say I draw heavily on both of these modes of perception/response. My work most often starts with a physical impulse or gesture with a sound attached to it--I am a very kinesthetic player, as much an idiosyncratic dancer as a conduit for sound. I then explore and develop that initial idea both intellectually and intuitively (more the former when I'm composing, more heavily the latter when I'm improvising/performing), and so begins a kind of back-and-forth between my ear/body/heart and my mind. But the ideal for me is when both are transcended, when I'm no longer aware of either, but just experiencing the music as it's being played/heard.

The flow I experience, when I’m following or allowing my natural impulse to guide the music, is really a kind of meta-flow. A state where I don’t have to think about what to play, but rather I know what note, what gesture, what shape or rhythm comes next, and it’s almost as if it happens without my doing anything. It’s a visceral response through movement and sound to what I’m hearing. Within that is the possibility for discontinuity or jagged gestures that are part of the flow, rather than something disruptive in the big picture.

If you think about the human experience and the natural world, within the cycle of life, there is becoming and dissolving, gentle breezes and destructive or turbulent winds, nourishing rain and torrential storms. Everything we experience and feel has the potential to be expressed through music and art. Leroy Jenkins turned me on to one of his favorite poems by Rumi, in it there’s a line that says, “We have fallen into the place where everything is music.” That’s an example of the experience I’m talking about.

Absolutely. It’s the just as important for me to practice this (both at my instrument and away from the instrument, say through meditation, yoga or in going about my day) as it is for me to work to become more expressive through acquiring greater technical facility and theoretical chops. And, as you suggest, it’s something I can work on when I practice, but it’s also something that seems to happen more and more when I’m performing, which I believe reinforces the experience, and makes it easier to drop into that space the next time. The practice is learning to recognize what kinds of thoughts or conditions cause me to disconnect from the music, and then it becomes easier to reconnect.